Importance of Context and Concrete Manipulatives From Kindergarten Through Grade 12

Like many other teachers, I was just teaching in a very similar way to that how I was taught.

I knew no different.

However, if we consider that new learning requires the linking of new information with information they already know and understand, we should be intentionally planning our lessons with this in mind. A great place to start new learning is through the use of a meaningful context and utilizing concrete manipulatives that students can touch and feel. When we teach in this way, we minimize the level of abstraction so students can focus their working memory on the new idea being introduced in a meaningful way.

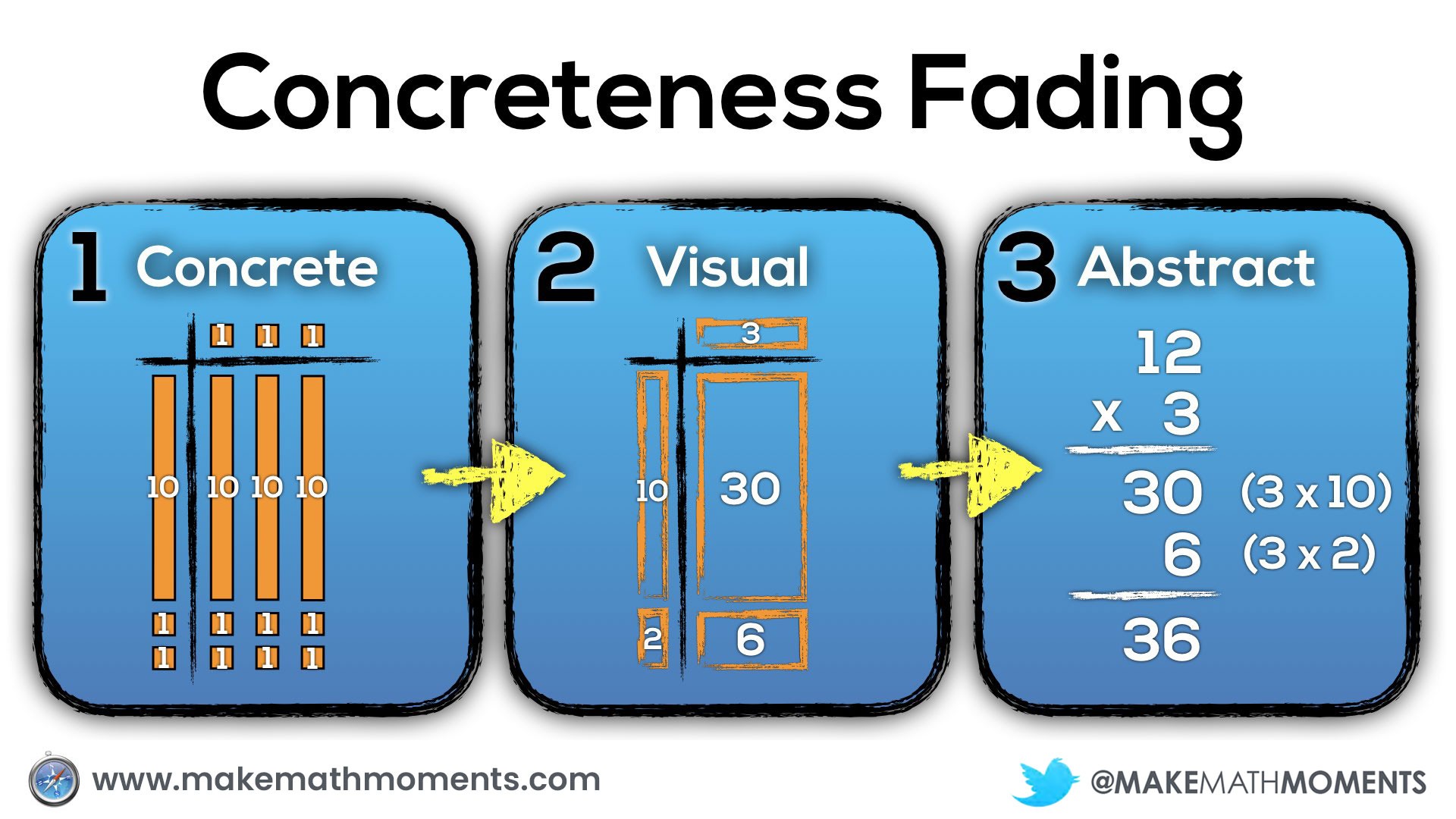

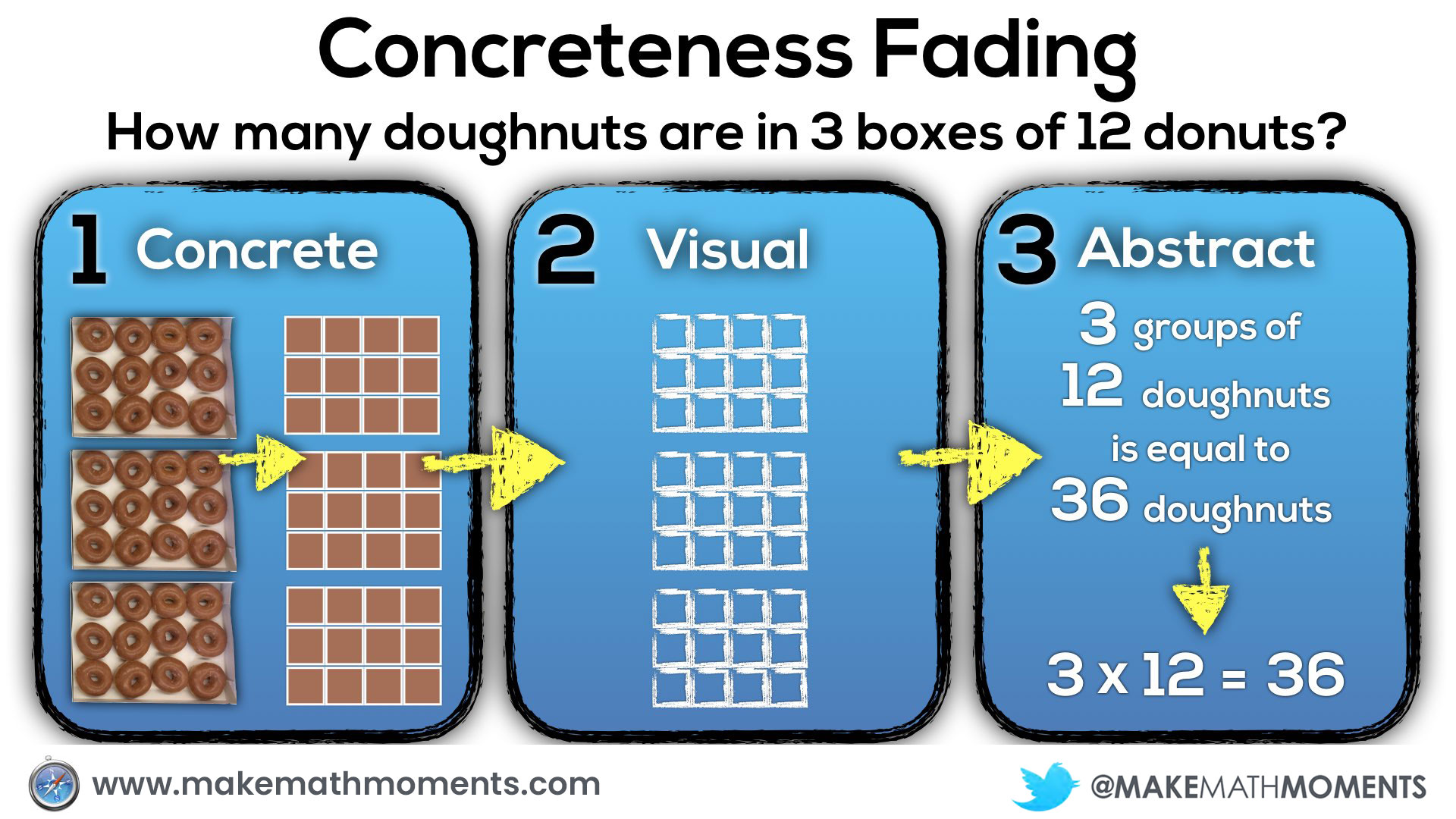

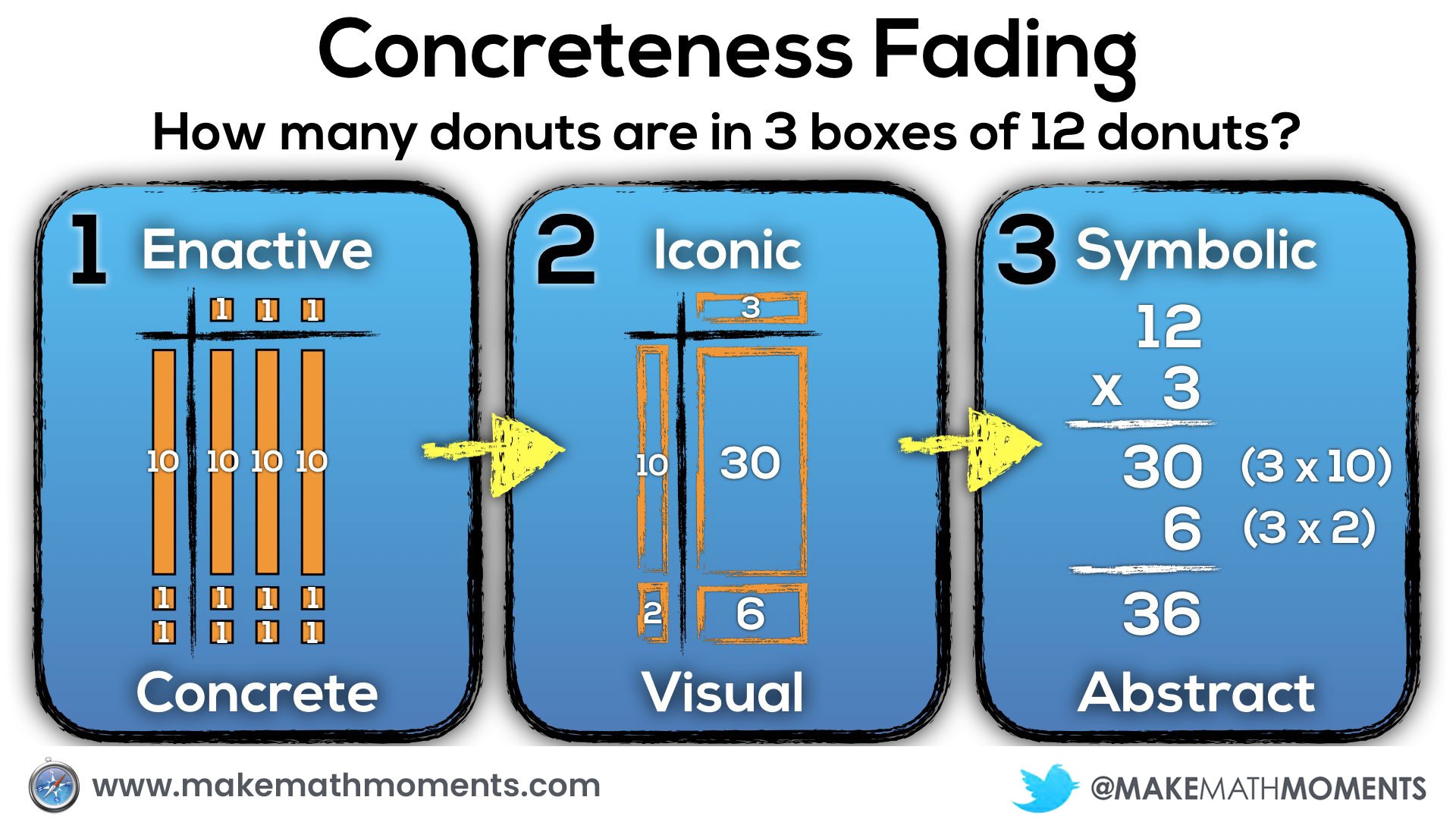

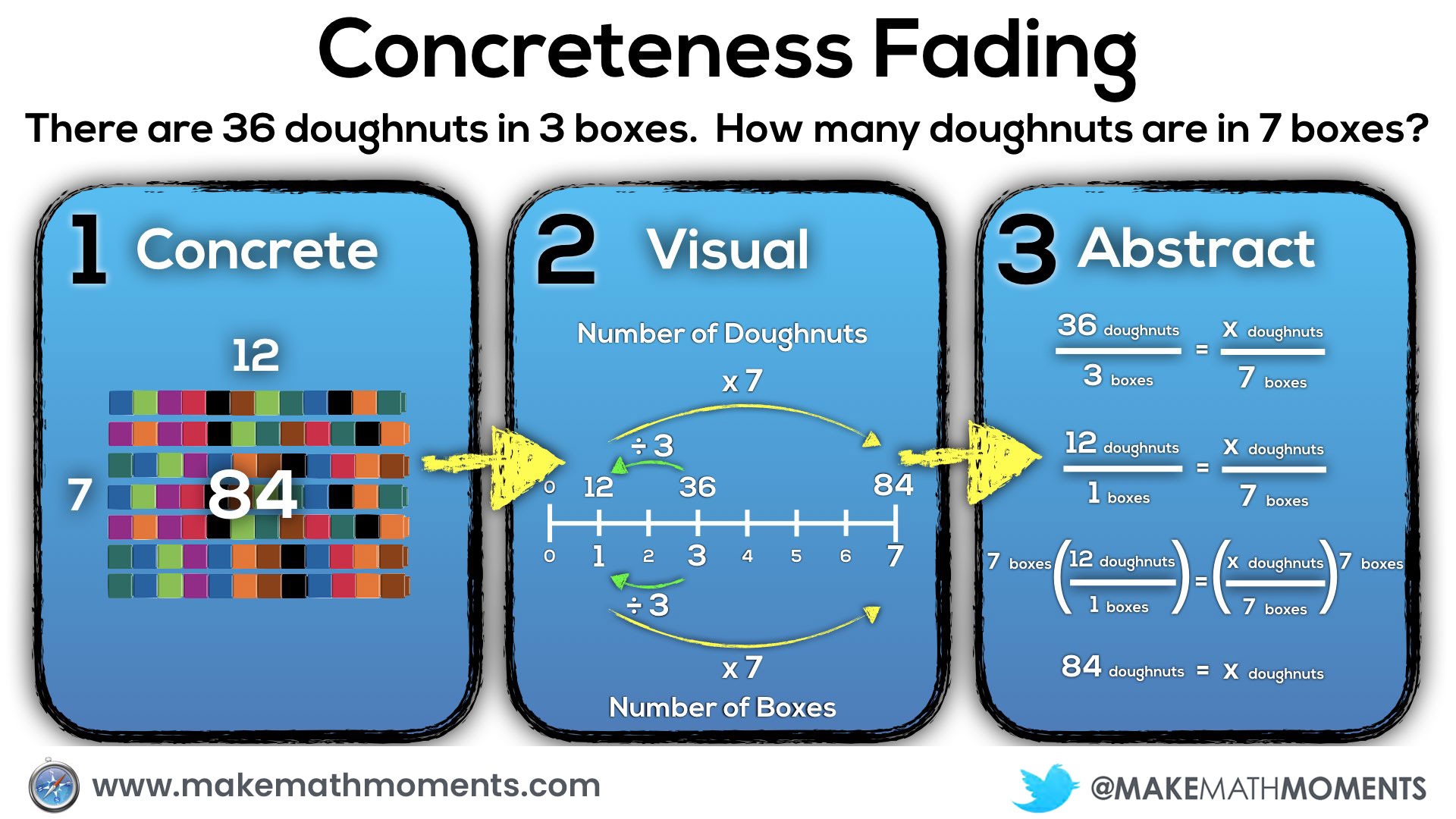

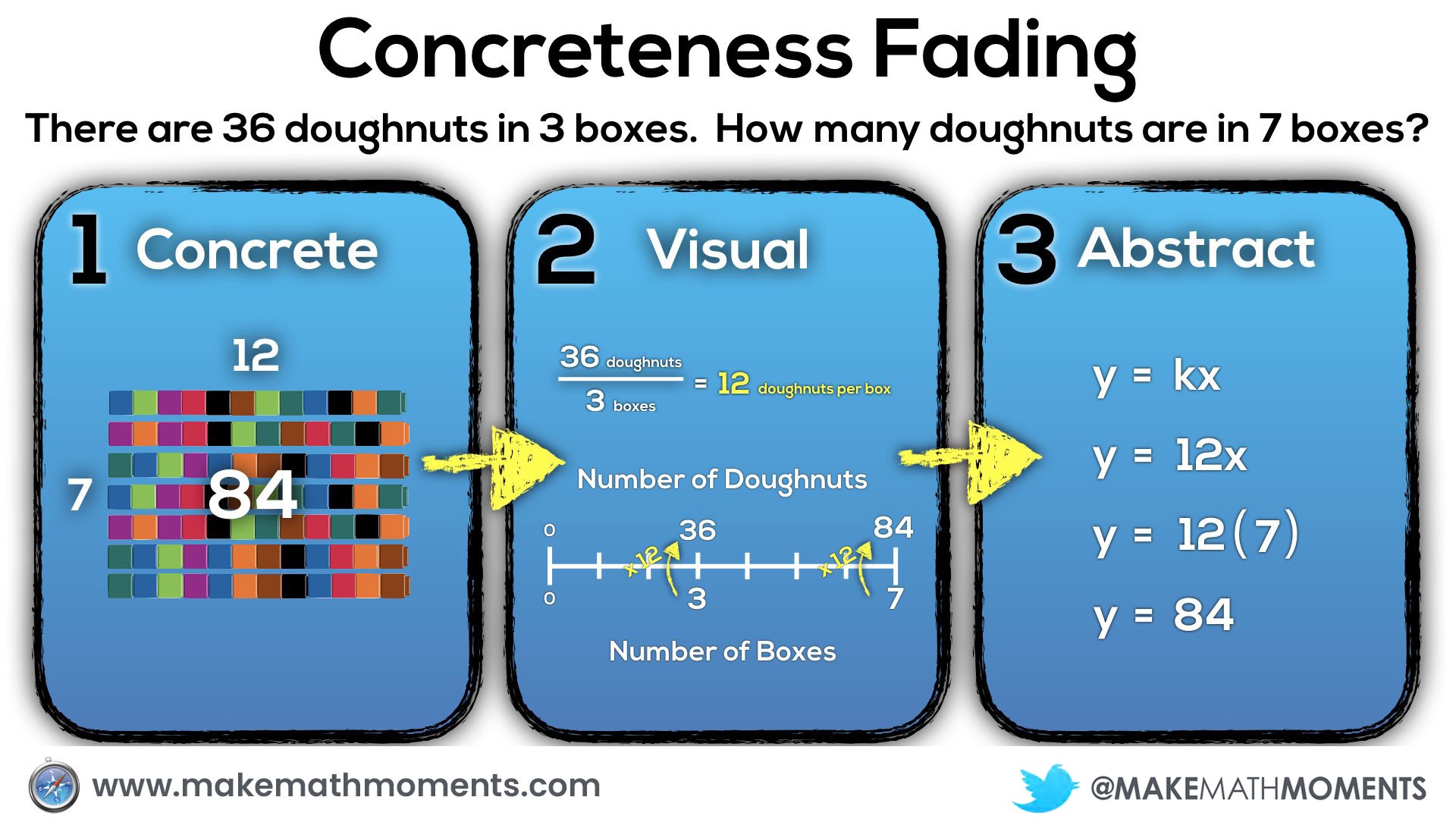

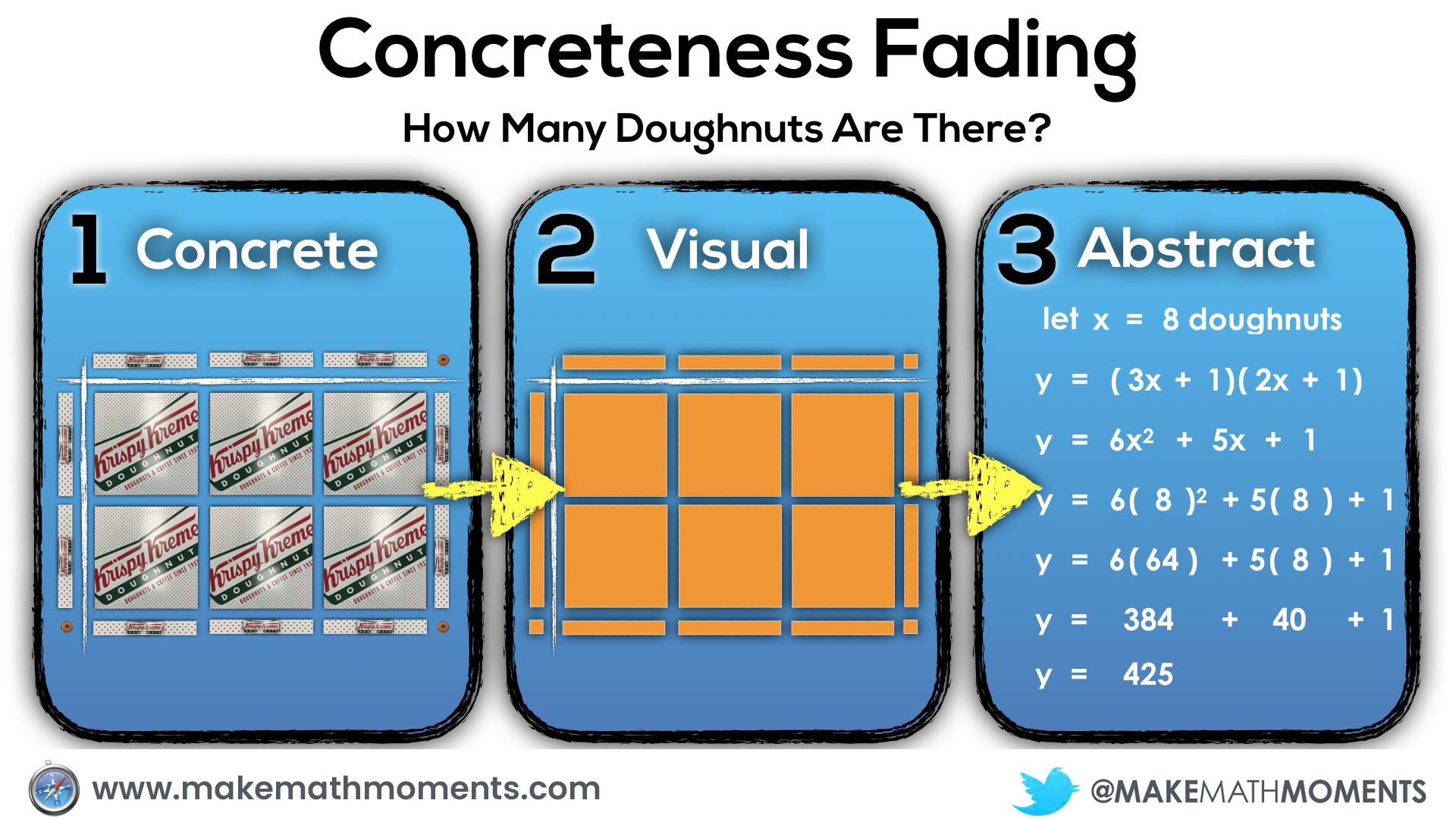

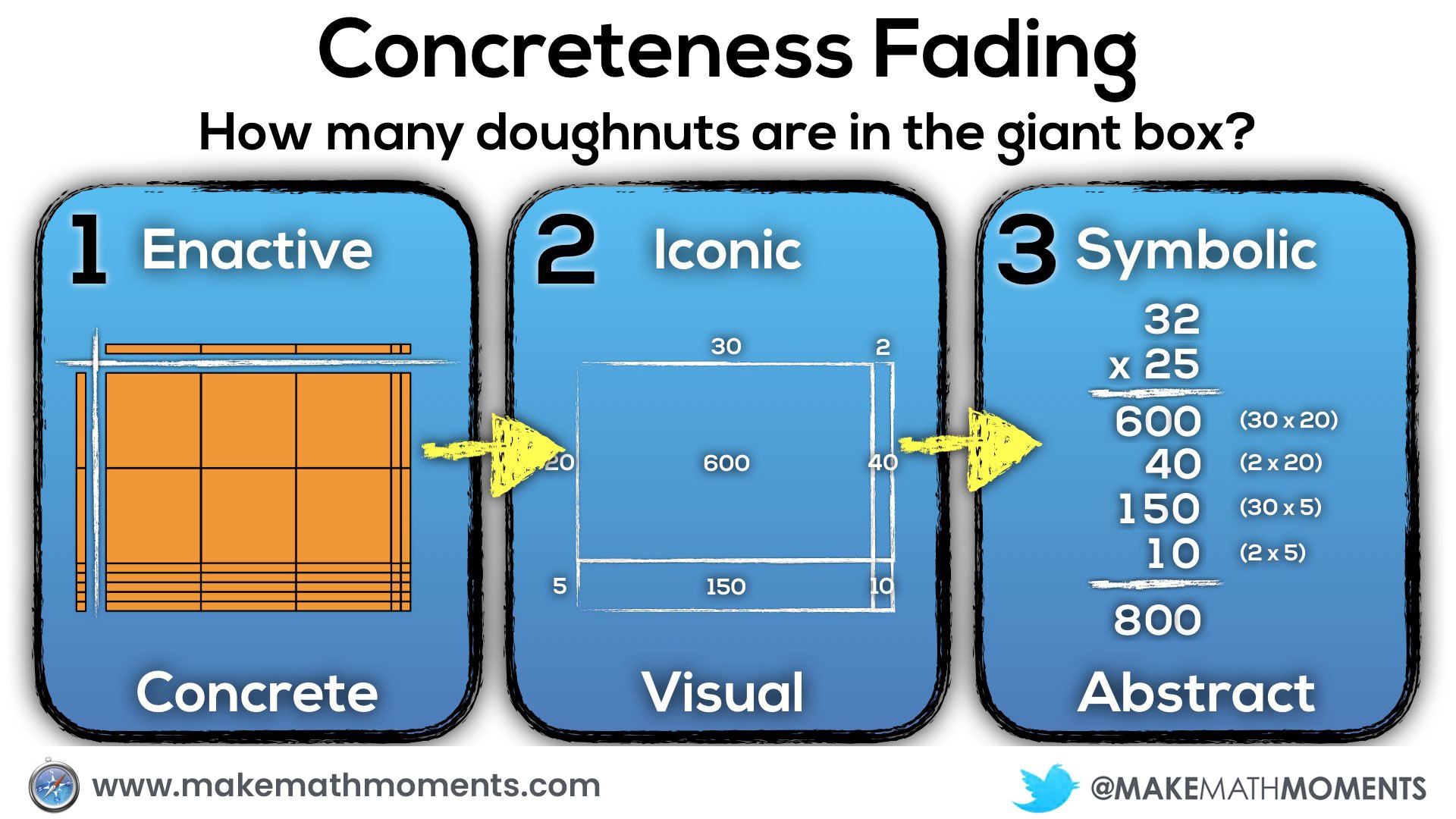

Concreteness Fading: Concrete, Representational, Abstract (CRA) Approach

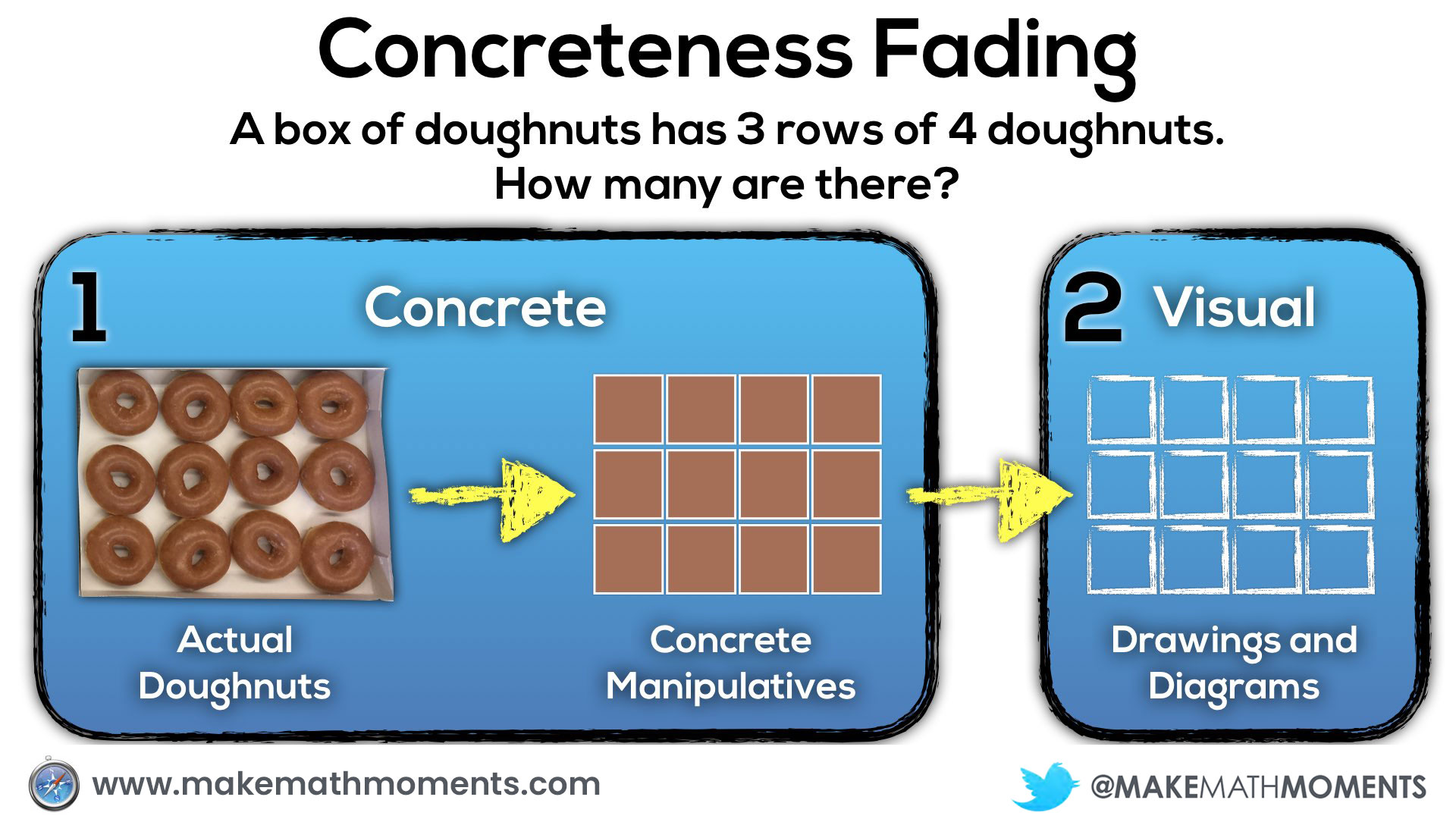

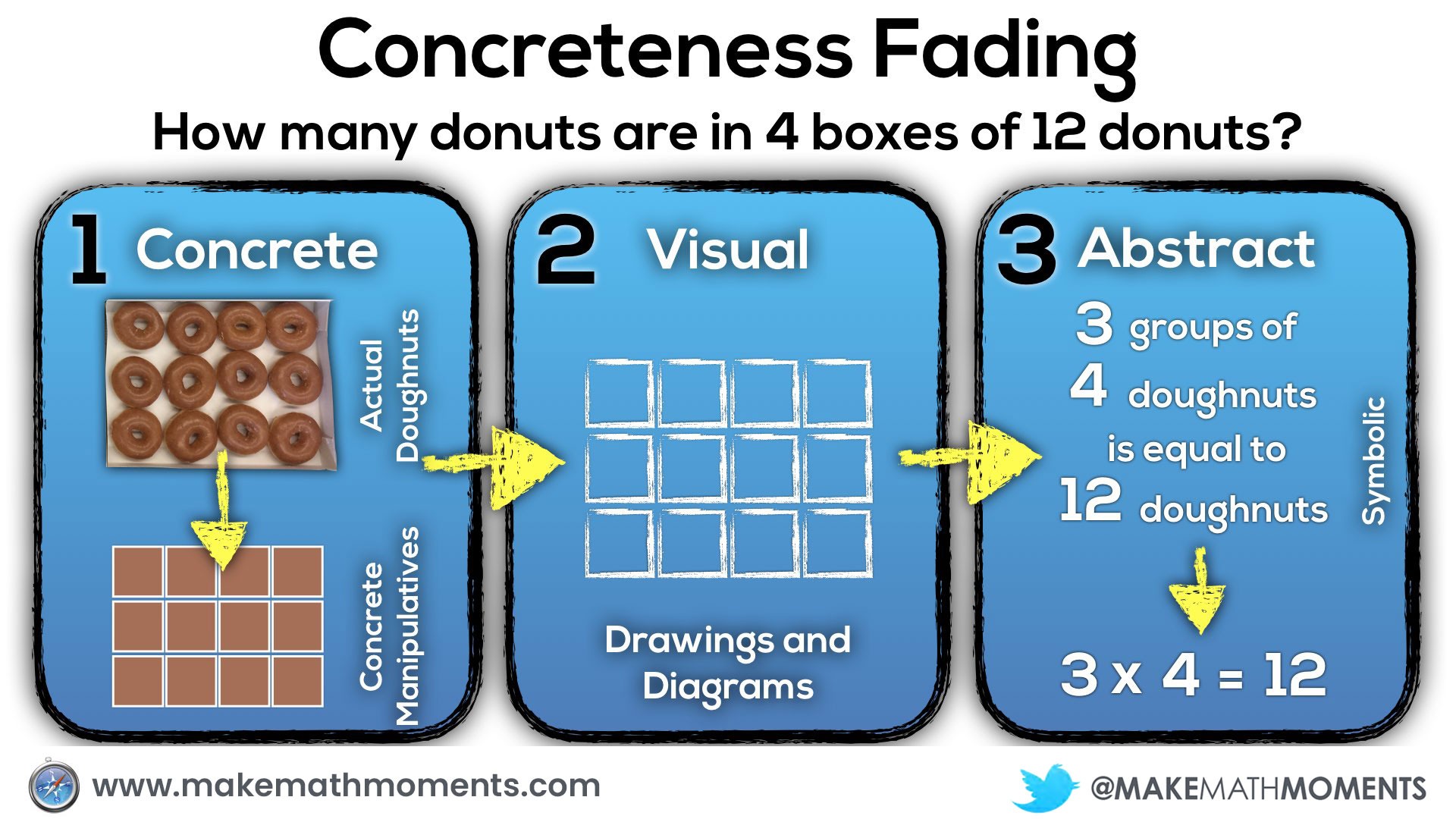

When we intentionally start with concrete manipulatives to learn new math concepts, our goal is to help students better construct an understanding of the mathematics in their mind. The goal is not to burden students with a big bag of manipulatives that they must carry around with them anytime they are required to do any mathematical thinking, but rather to ensure that they can build their spatial reasoning skills physically – through the manipulation of concrete objects – so they can begin to visualize mathematics in their mind. When a student is able to “look up” as if they are peering into their mind to visualize their math thinking, we know students are thinking conceptually rather than simply following a memorized procedure.

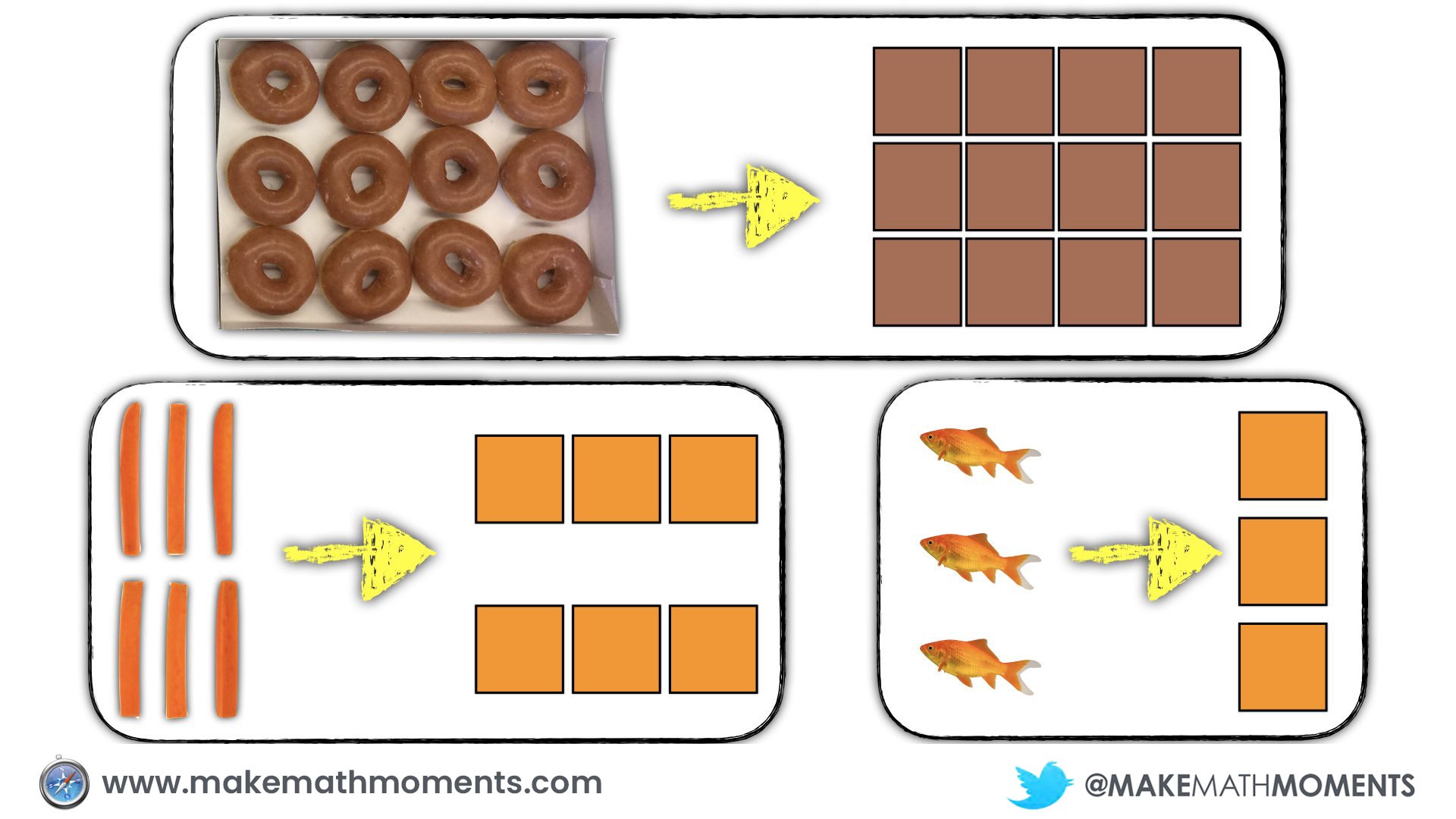

While students are working with concrete manipulatives, it is helpful for the teacher to model visual representations of the student work for all to see. By introducing these visual drawings of the concrete representations students are creating, it will be easier for students to shift away from concrete manipulatives and towards visual (drawn) representations when they are ready.

When students have built an understanding both concretely and visually, we can then begin moving to the final stage called abstraction where we use symbolic notation. The goal here is that when students use the symbolic notation, they can visualize what the concrete representation of that mathematical statement represents.

Some know this idea as concreteness fading, while others have called this progression concrete, representational, abstract (CRA). In either case, the big idea is the same. Start with concrete manipulatives, progress to drawing those representations and finally, represent the mathematical thinking abstractly through symbolic notation.

Let’s look at a couple different questions at different grade levels where using context and concrete manipulatives can lower the floor and help us progress towards more abstract representations.

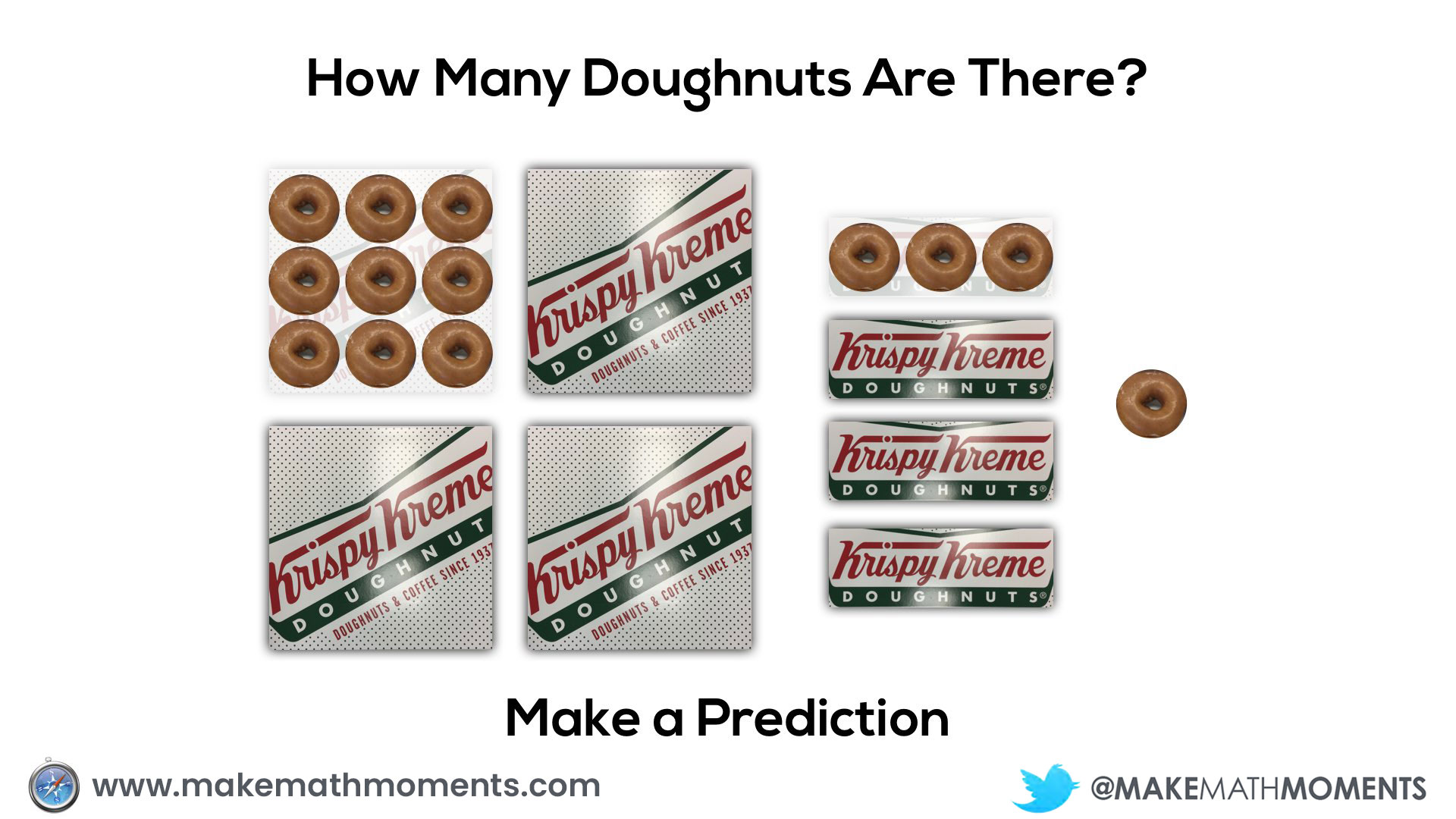

After students talk with a neighbour and share out their predictions, I would say:

This box of doughnuts has 3 rows of 4 doughnuts.

In a perfect world, we could give them real doughnuts (or bagels, to be health conscious) so they could recreate the situation right in front of them:

As students use concrete manipulatives to build their conceptual understanding of a new idea, they will begin to feel burdened by the manipulatives and seek out less cumbersome tools and representations to show their thinking. If the teacher has been drawing visual representations of the concrete representations students share with the group along the way, many will eventually transition to drawing their representations rather than building them concretely. However, for other students who have seemingly mastered the concrete representations but are not shifting to visuals, we may need to help scaffold them along.

For example, in the abstract / symbolic phase, you’ll notice the words:

“3 groups of 4 doughnuts is equal to 12 doughnuts”

By no means am I suggesting that we should wait until the concrete and visual phases are mastered before using those words. I would actually suggest that we are verbally saying those words during the concrete stage and even possibly writing down that sentence during the concrete stage since there are no new symbols or abstract ideas being introduced by doing so. With an idea like single digit multiplication, you might consider having students build the concrete representations and the teacher may draw the visual representation as well as the symbolic representations at the same time.

The key with concreteness fading is that we are aware of these three phases and we use our professional judgement to determine when to introduce each phase as to push student thinking forward without overwhelming them with too much abstraction too quickly.

Assuming students have had a substantial amount of experience building concrete representations of multiplication, you may see students skipping right over the concrete phase to the visual stage creating drawn diagrams of this situation. This is absolutely fine as a student who is able to draw what the concrete representation should look like suggests that she could indeed build that representation if required. Furthermore, this also suggests that this student is now able to create a more abstract representation of that concrete model, which is what we are hoping to develop.

What I would not advocate is completely skipping over the first two phases and focusing only on the symbolic representation. Despite the fact that some students may have a visual of that concrete model clear in their minds, we don’t want to promote students relying solely on procedural fluency and risk forgetting all of that conceptual understanding we worked so hard to build. By giving students enough practice drawing visual as well as abstract or symbolic representations, they are utilizing their conceptual understanding and procedural fluency in tandem, where they can be used most effectively.

Concreteness Fading is Cyclical

As students become more comfortable with the abstract representation of multiplying 2-digit numbers by 1-digit numbers, we might think it is fine to start with the abstract stage of concreteness fading when we progress to 2-digit by 2-digit multiplication. Although we have progressed through the stages of concreteness fading for one concept, as we add a new level of complexity (i.e.: adding another digit to multiplication) we should be cycling back to the concrete stage to lower the floor for all students to access this new learning.

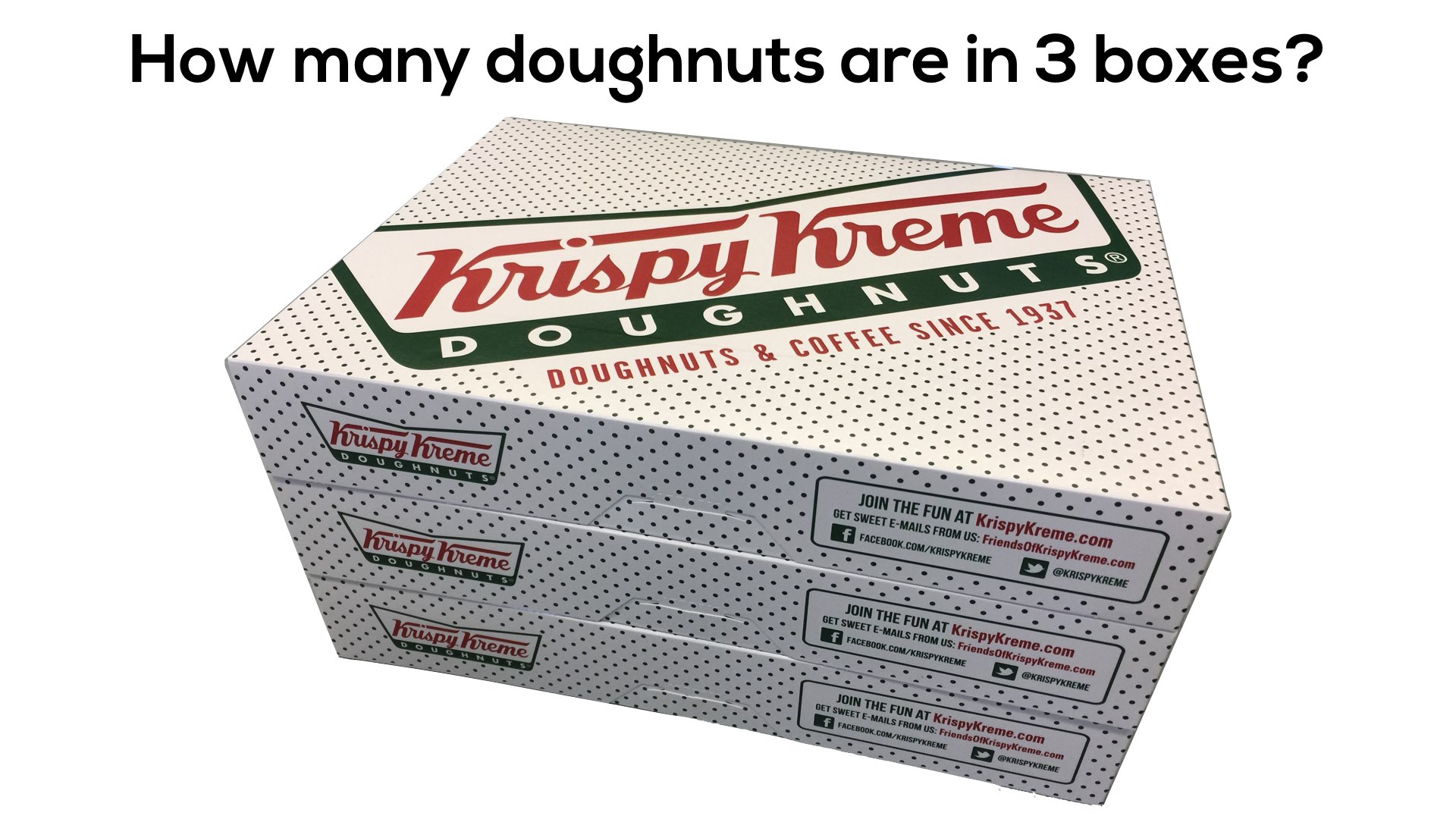

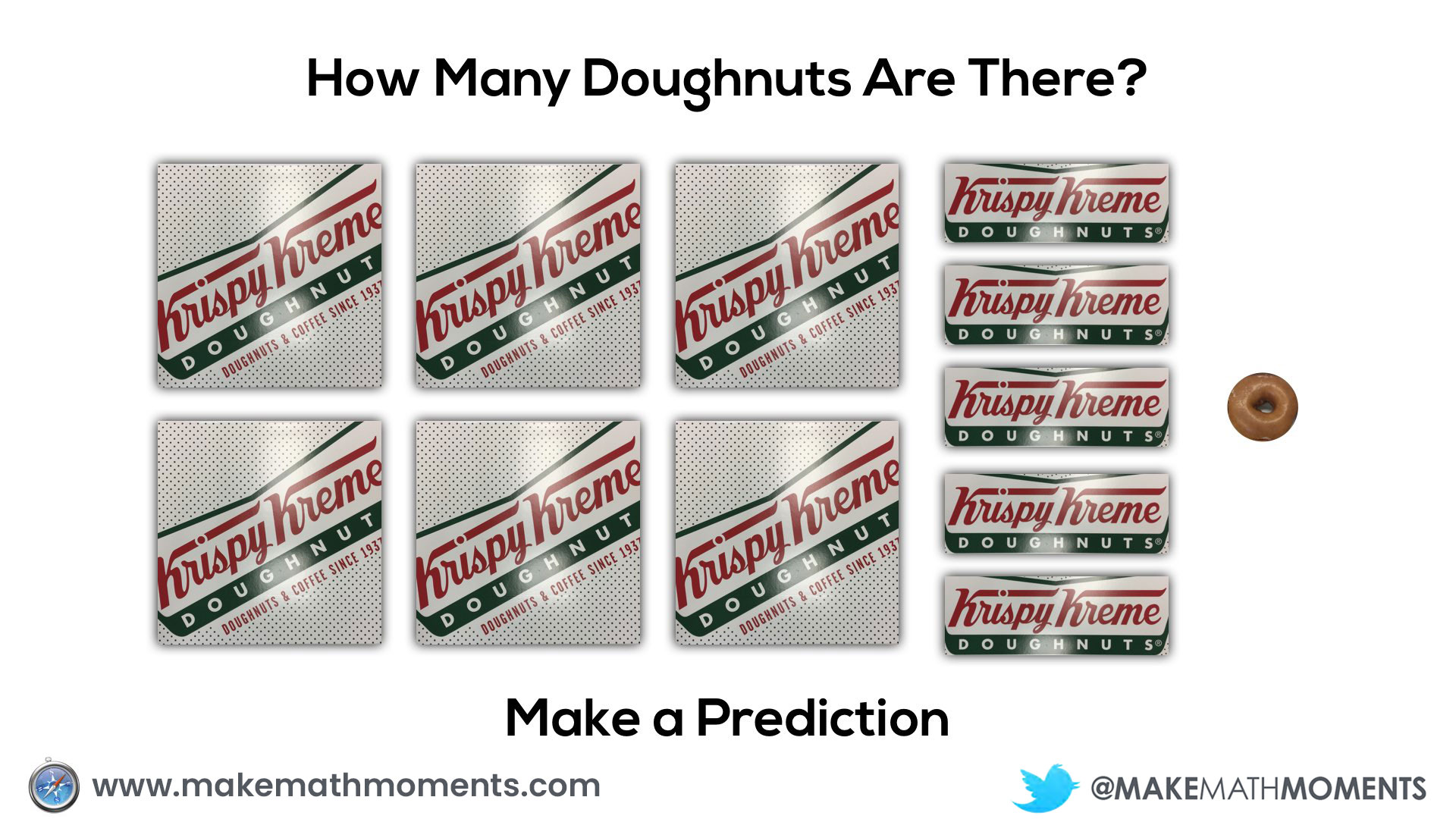

A great example that works well here is the 3 act math task, Doughnut Delight.

After students notice and wonder, we land on the question:

How many doughnuts are in that giant box?

There are 32 rows and 25 columns of doughnuts.

They are then set off to find a solution using an effective strategy of their choosing. Assuming this is their first exposure to 2-digit by 2-digit multiplication, starting in the concrete stage using base-10 blocks would be appropriate. For students who may already have made connections to the work they have done previously, they may choose to draw out an array or use another visual model to show their thinking.

Here in Ontario, we explicitly introduce 2-digit by 2-digit multiplication in grade 5. Every time I’ve used this task with students in grade 5, most are rushing to the algorithm and making errors due to the lack of conceptual understanding.

I do my best to try and get students to back up a stage or two in order to truly understand the mathematics we are asking them to grapple with. This can be a struggle, because often times students just want to get “an answer” and move on.

However, if they are shown how easy multiplication can be by having a conceptual understanding in their back pocket, they will eventually jump on the opportunity.

Here’s what concreteness fading could look like for this task:

- Donut Delight – 3 Act Math Task

- Progression of Multiplication – Where does the standard algorithm come from?

Scenario #3: Middle School Classroom

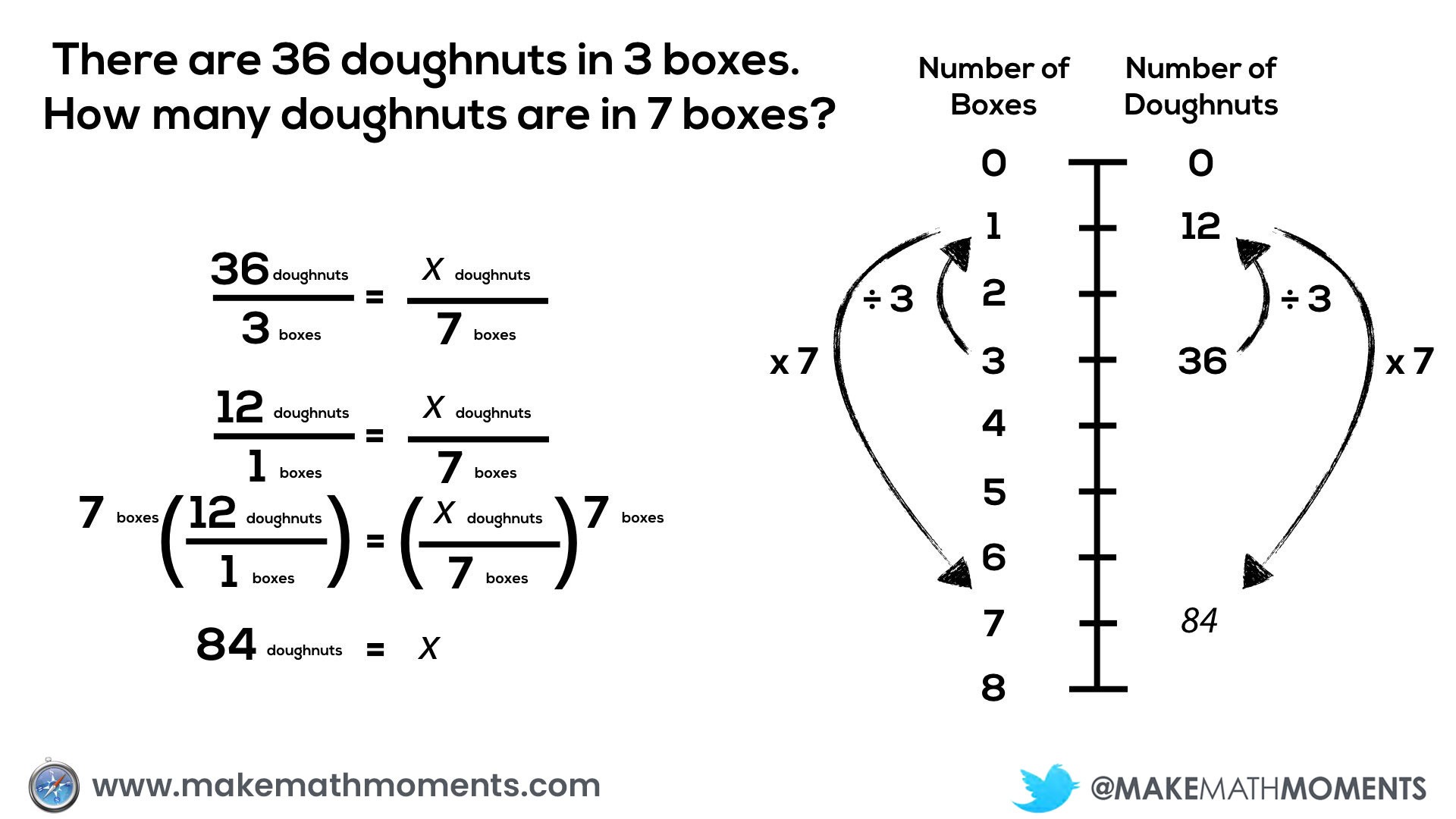

In a middle school classroom (end of junior/intermediate classroom in Ontario), the question might sound more like this:

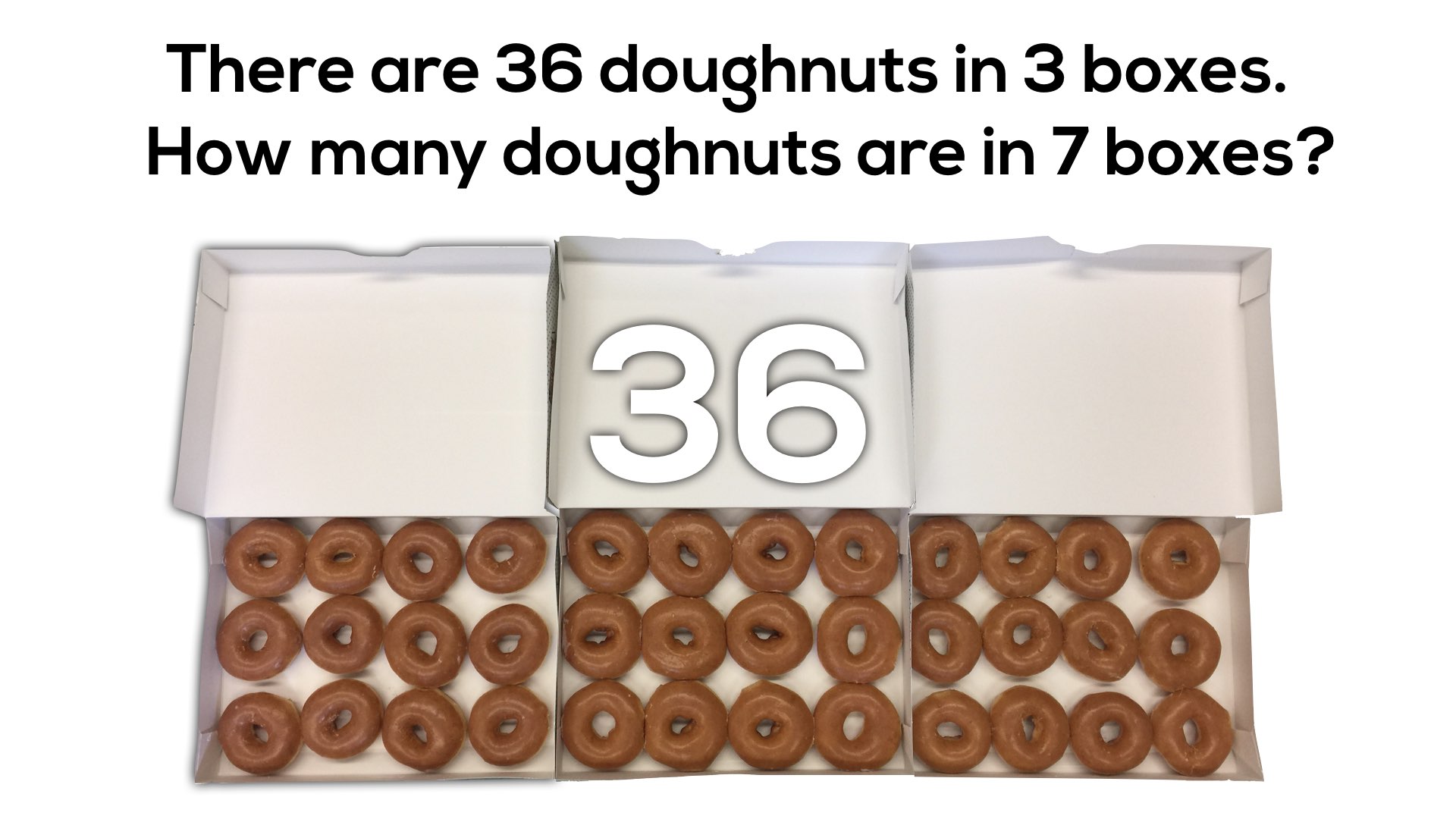

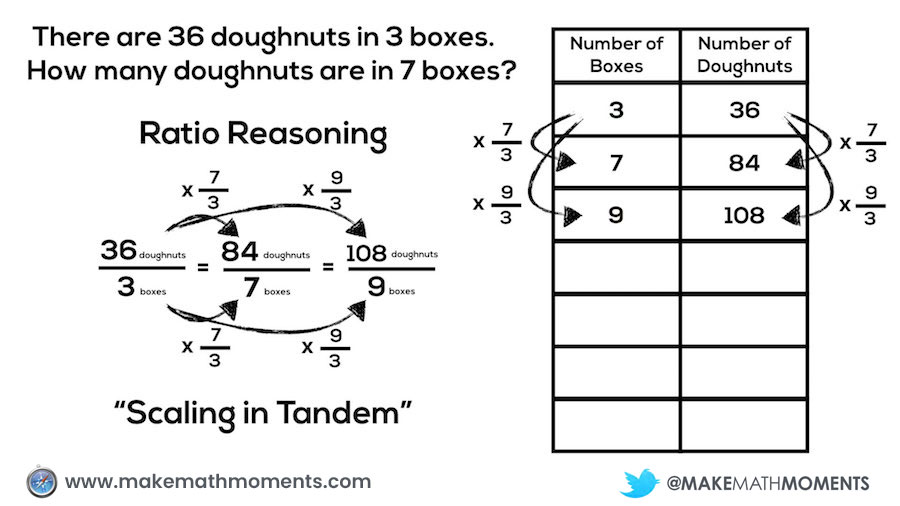

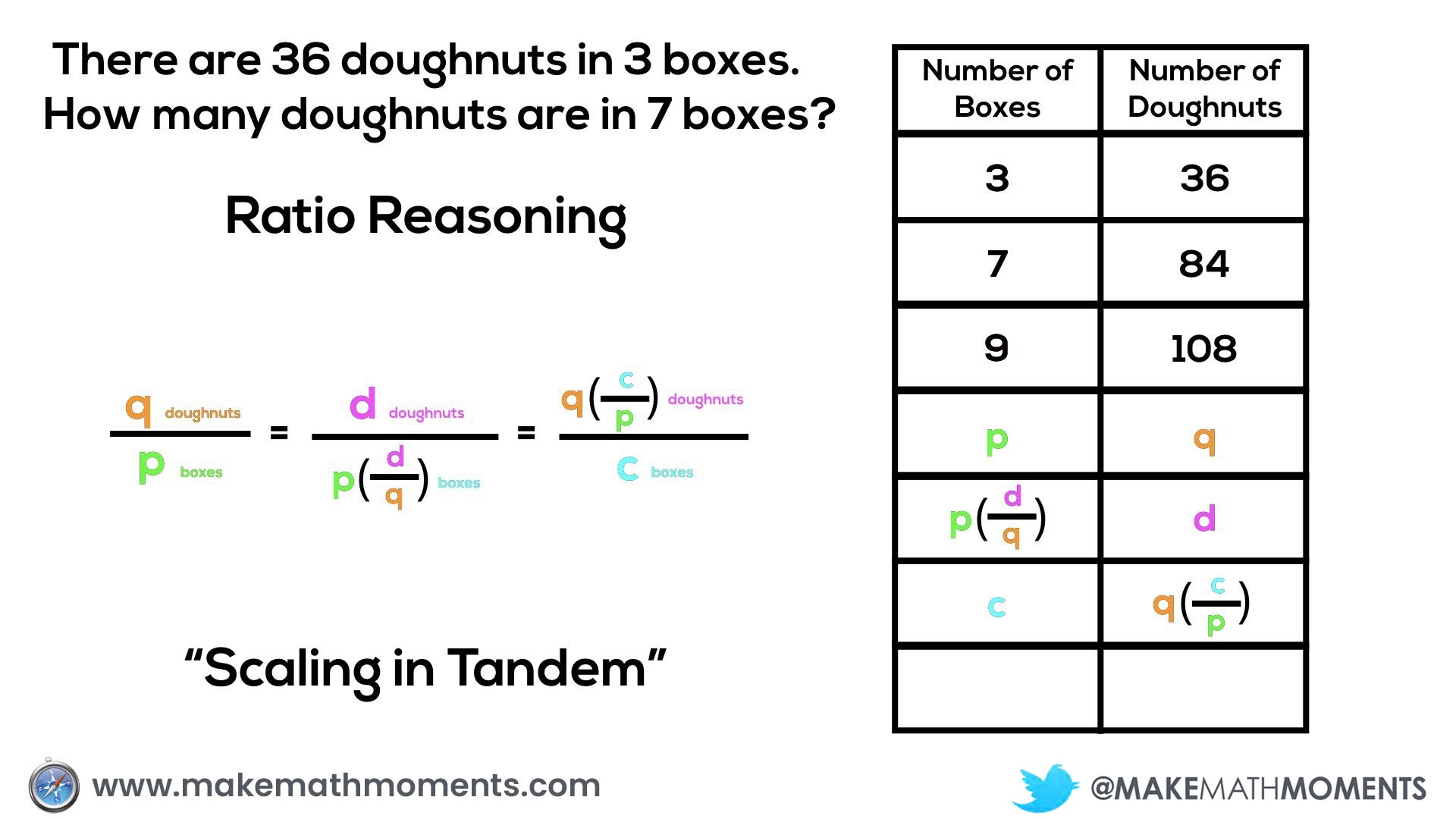

There are 36 doughnuts in 3 boxes.

How many doughnuts are in 7 boxes?

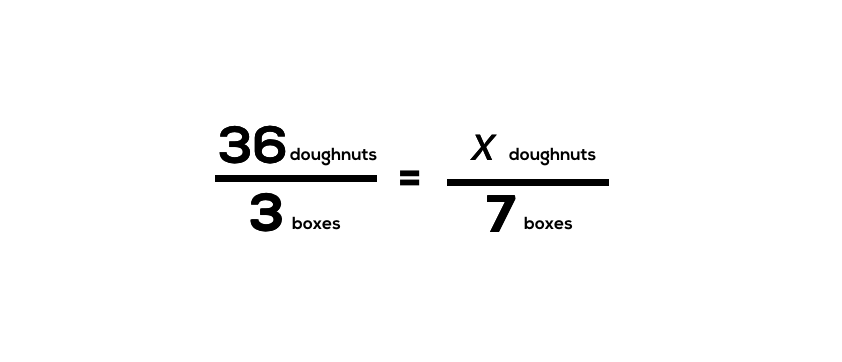

Despite the fact that proportional reasoning is introduced explicitly in the Ontario Grade 4 Math Curriculum, many of our grade 9 students continue to struggle with this type of reasoning. Many may not have fully conceptualized the prior knowledge necessary for them to be successful at that particular grade level. Before I understood the power of concrete and visual representations, I can recall trying to help students in my grade 9 (and sometimes grade 10) class by breaking down the symbolic representation with more symbols.

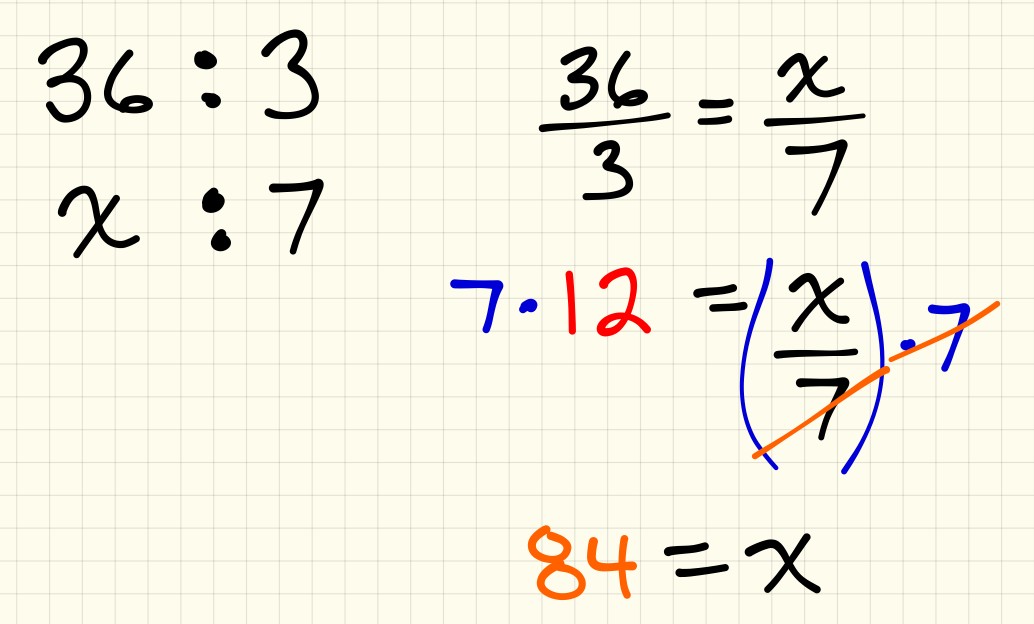

For example, with this particular problem, I might have attempted unpacking the problem with students by creating a proportion and solving for the unknown:

How might I have approached this same problem had I known and understood the concreteness fading model?

Well, I would definitely start with concrete manipulatives for all of my students. Just because a student is able to solve familiar problems using all the right steps and procedures does not necessarily mean that they have a conceptual understanding of the mathematics they are employing.

One possible idea could be giving students connecting cubes and having them model out the situation. They might start by grabbing 36 cubes and dividing them to the 3 boxes. Then, they could double the 3 boxes of doughnuts to get 6 boxes and add an additional box.

For example, you might ask students:

How many times bigger is the quantity in 7 boxes than in 1 box (i.e.: 7 times bigger)?

How many times bigger is the quantity in 7 boxes than the quantity in 3 boxes? (i.e.: 2 and 1 one-third times bigger)

While I try to encourage all students to make a concrete model, some may be moving away from physical manipulatives and pushing towards a visual model which would suggest that they are ready to move one step deeper into abstraction.

Here’s an example of how a double number line could be used to help students visualize the situation and problem solve their way to a solution.

The more I can help my students link their concrete and visual models to more abstract representations, the stronger their conceptual understanding will be to help support any procedural approaches they wish to use to progress towards more efficient methods.

Had I known more about concreteness fading earlier in my career, the progression might have looked more like this:

Let’s take a closer look.

Fuel Sense Making: Scaling in Tandem and The Constant of Proportionality

I have been blessed to be a part of an amazing group of mathematicians funded through the Arizona Mathematics Project (AMP) to make sense of proportional relationships and this group of 18 mathematics education influencers have landed on some really useful definitions related to this very commonly encountered type of middle school math problem.

When we look at the animation of the concrete model using connecting cubes, you can see the two methods of attacking proportional relationships that the AMP group refers to as:

- scaling in tandem; and,

- using the constant of proportionality.

We can see the use of scaling in tandem when we see the doubling the number of boxes and number of doughnuts from 3 boxes, 36 doughnuts to 6 boxes, 72 doughnuts.

We can see the use of the constant of proportionality when we look at the number of doughnuts (12) in a single box – often referred to as the unit rate.

First, we will head a bit further down the concreteness fading continuum by taking our horizontal double number line and represent it as a vertical number line. This is a nice way to progress towards a table of values without losing the relative magnitude between each quantity on the number line.

What we are referring to here is the limited usefulness of setting up a single proportion for a “rule of 3” problem.

While I do not want to advocate that we avoid proportions altogether, I would much prefer giving students the opportunity to explore these problems more deeply and allow for the students to stumble upon some of the procedures we see taught explicitly in middle school classrooms.

Let’s look at where we might start.

Ratio Reasoning: Scaling in Tandem

We can see from the animation below that scaling in tandem is responsible for allowing us to solve a proportion using any of the procedures we see taught in many middle school math classrooms:

If students are encouraged to utilize scaling in tandem with double number lines, tables and equivalent fractions, over time we can help students see that some of this scaling can be done more efficiently:

For example, we can find the number of doughnuts in 9 boxes of doughnuts by scaling in tandem by multiplying both 36 doughnuts and 3 boxes by 9/3 or 3:

q/p = d/c

qc = pd

c = pd/q

or

d = qc/p

While I taught tricks like cross-multiplication, “the magic circle” and “y-thingy-thingy” before I constructed a firm conceptual understanding of proportional relationships, the reality is that they provide a dead end pathway to a single answer rather than an understanding that allows you to own the problem.

So rather than simply teaching a trick using steps and procedures, let’s give students an opportunity to build a conceptual understanding of scaling in tandem and challenge them to come up with their own procedures and algorithms.

Rate Reasoning Using the Constant of Proportionality

While we can use ratio reasoning and scaling in tandem to up the conceptual understanding over solving a “rule of 3” problem using a proportion, we still don’t “own” the problem yet.

Under the hood of every proportional relationship lies a constant that we can use to solve ANY problem related to the proportional situation. This constant of proportionality can be found by taking the quotient of any two covarying values in the relationship.

Many know this constant of proportionality as the unit rate.

In the case demonstrated here where the number of doughnuts is proportional to the number of boxes, we can determine the number of doughnuts in any number of boxes by multiplying the number of boxes by 12 doughnuts per box, while we can determine any number of boxes by multiplying the number of doughnuts by 1/12 boxes per doughnut (or dividing by 12 doughnuts per box).

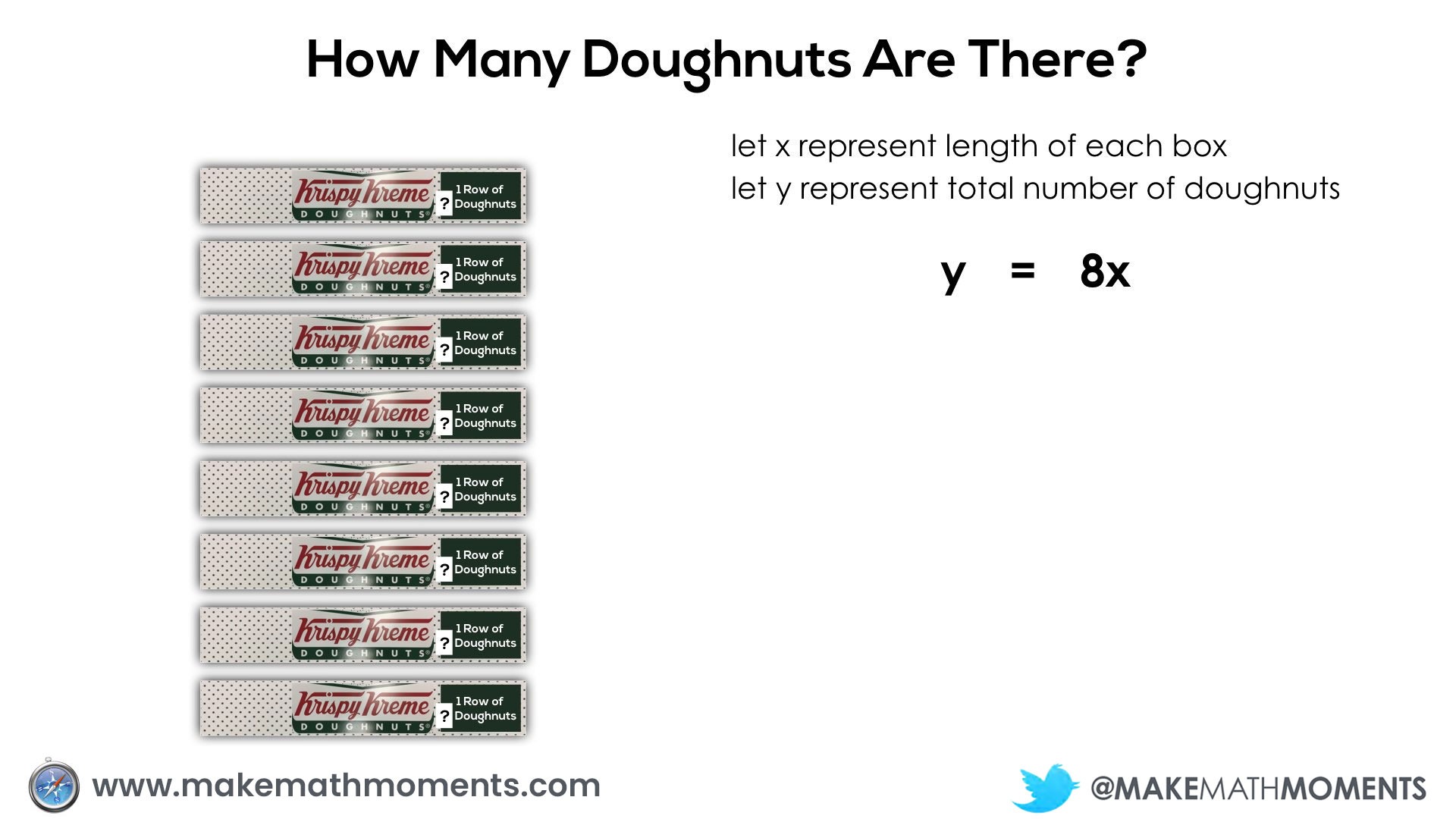

Scenario #4: Middle and High School Classroom

In grade 8 classrooms here in Ontario, we start making a serious push towards deeper algebraic reasoning and functional thinking which carries over into the deep exploration of linear and quadratic relationships in grades 9 and 10. While the context for doughnuts may not be my favourite – despite all their yummy-ness – it is possible for us to extend our thinking around this context from multiplicative and proportional reasoning to algebraic and functional thinking.

In this case, we’re going to continue exploring some situations where the goal is to figure out:

How many doughnuts are there?

In the first scenario, we’re looking at a 1 row box or “strip” of doughnuts, however we do not know how many are in each box initially:

Since a proportional relationship exists between the number of doughnuts and number of boxes, we can use our understanding of the constant of proportionality to help us create an equation for this situation.

If we assume (or we are given) the number of doughnuts in each box, we can then determine how many doughnuts in total.

In this next situation, we are given 8 square boxes and we know the total number of doughnuts is 72.

If a student uses ratio reasoning, scaling in tandem might look something like this using a concrete and/or visual representation:

Having them share with their partner how they came up with their prediction can be extremely useful to see what they notice about each of the boxes. The goal here would be for students to make the connection that each doughnut “strip” box is the same length as the square box dimensions.

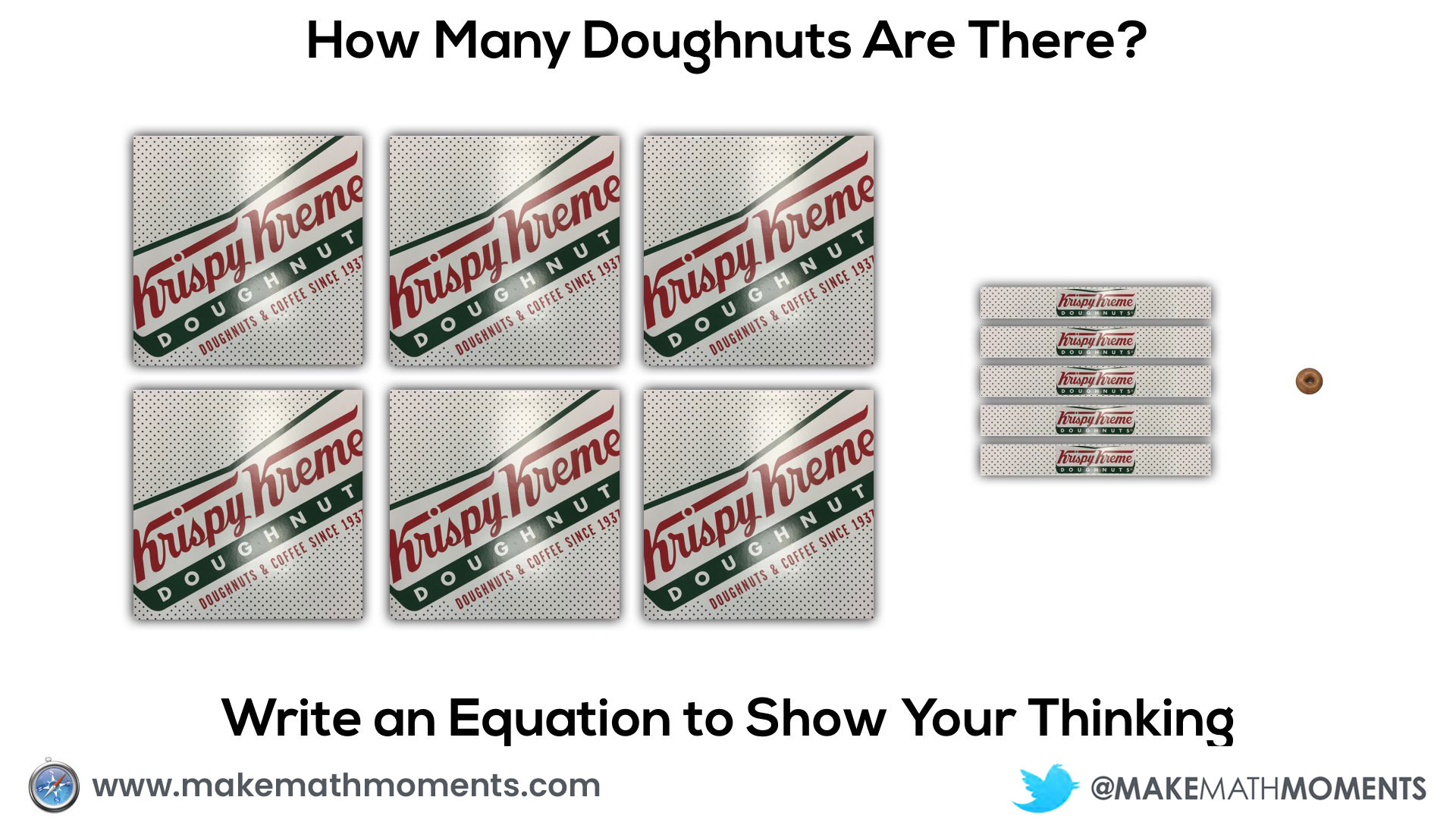

You can then share some more information and have them update their prediction:

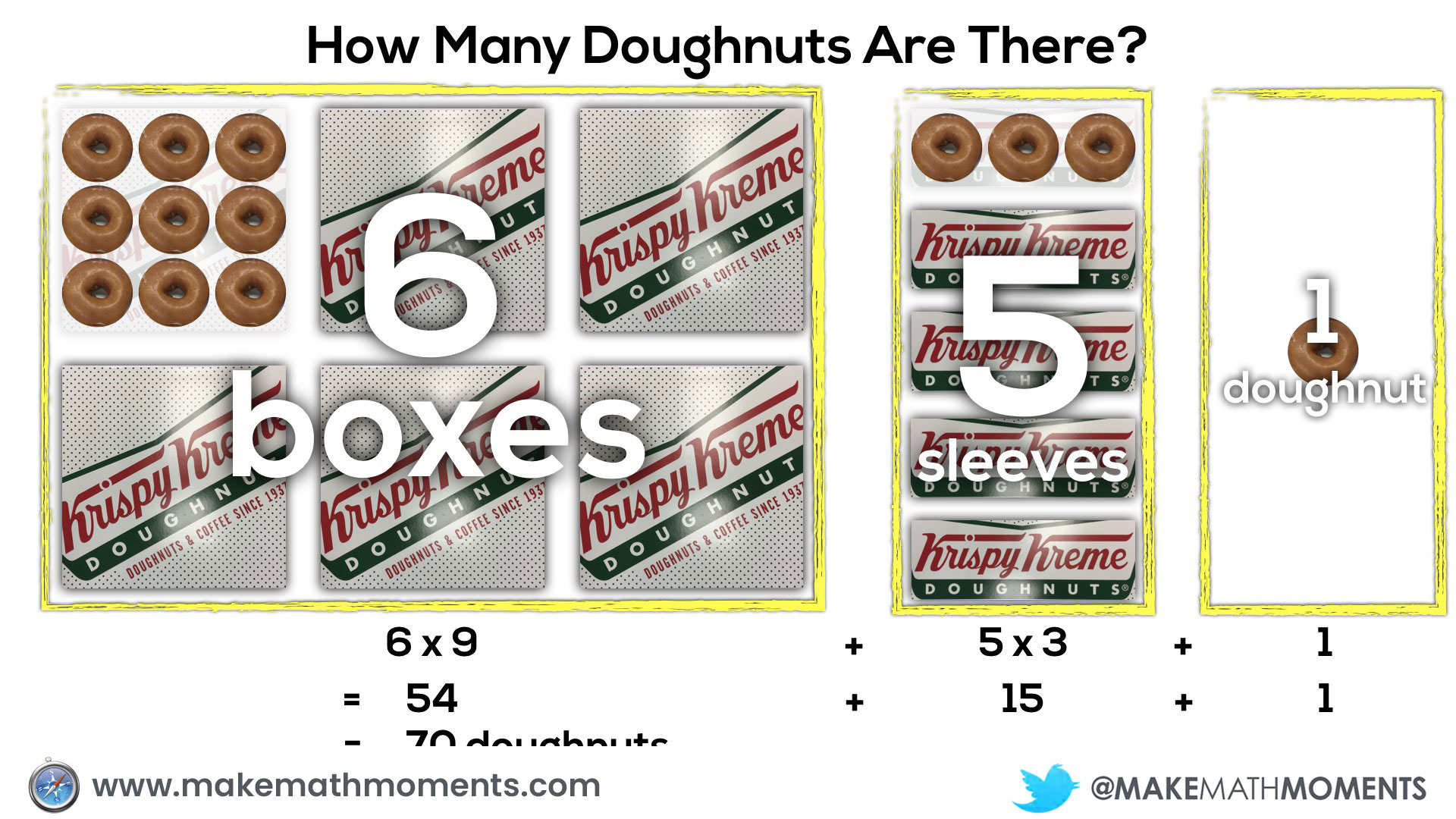

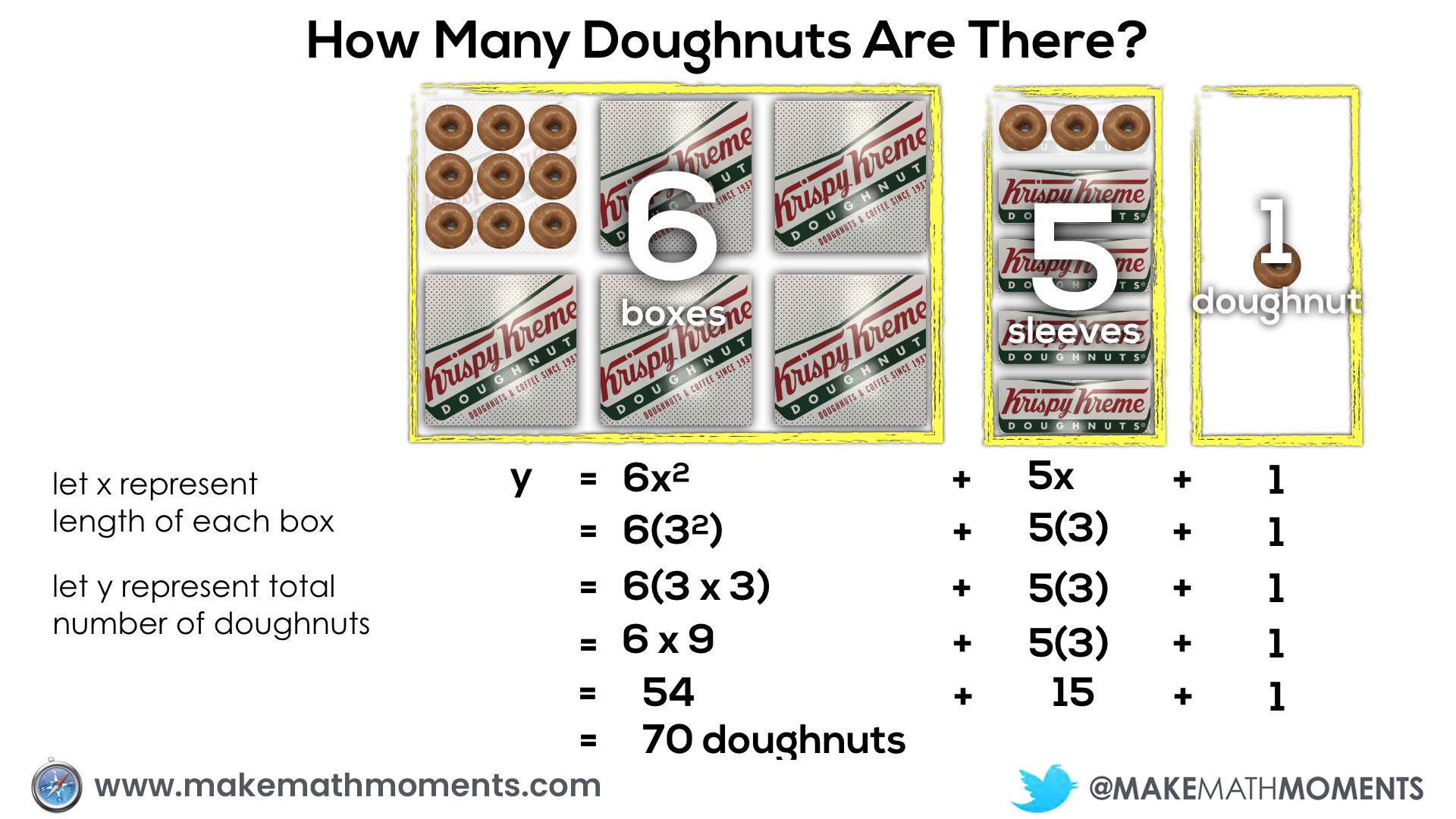

Initially, they may do this verbally by describing the 6 square boxes, the 5 single row “sleeves” of doughnuts and the 1 extra doughnut. Since they know that there are 9 doughnuts in each square box and 3 doughnuts in each single row “sleeve”, it might sound like this:

6 boxes of 9 doughnuts plus 5 boxes of 3 doughnuts plus 1 doughnut

Here’s a visual of substituting a value of x into a quadratic equation and simplifying:

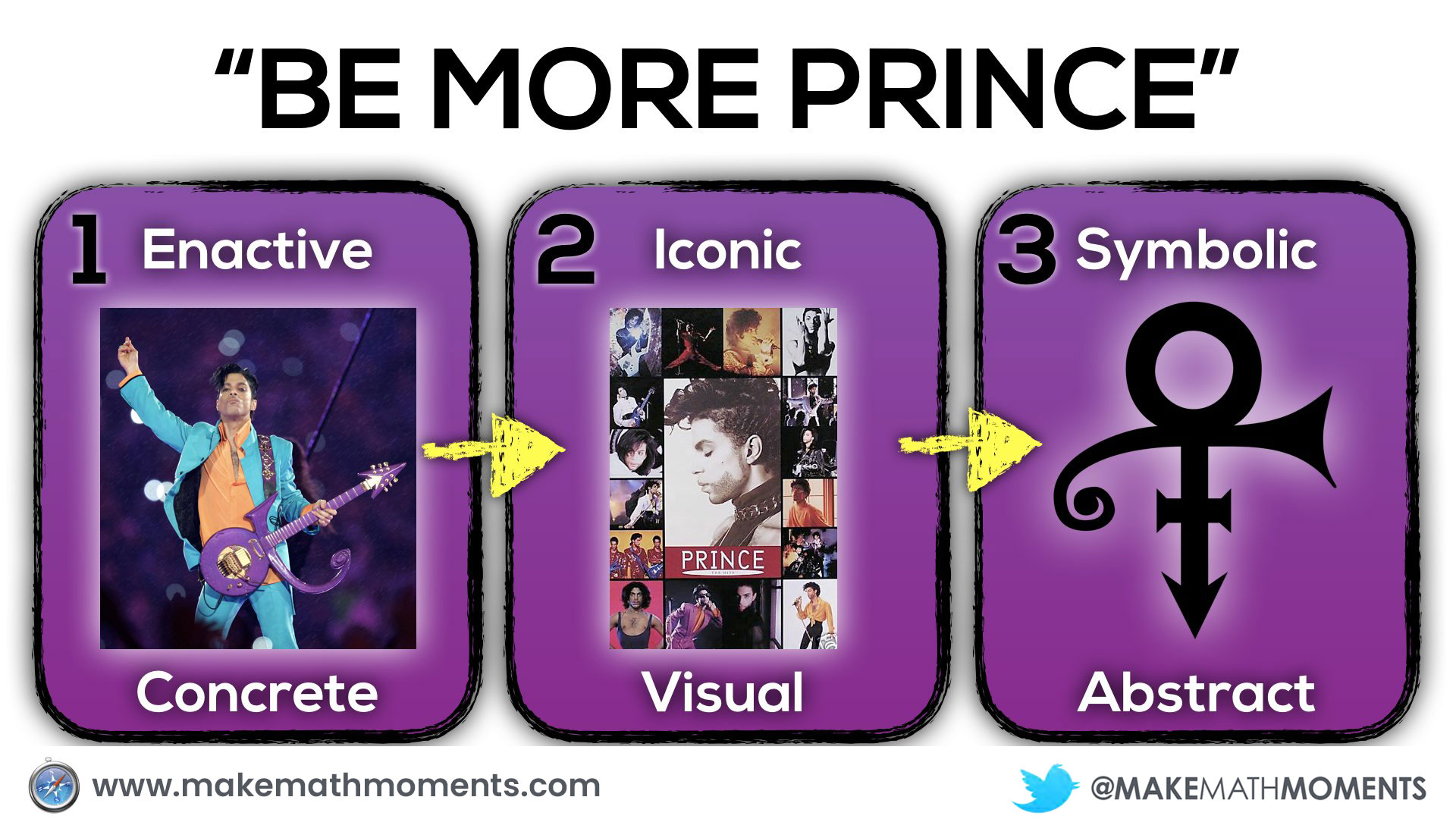

If Prince Knew About Concreteness Fading, Why Didn’t I?

For years, I was spinning my wheels trying to teach students how to make sense of mathematics through abstract representations. However, even musicians are aware of the importance of marketing through a concreteness fading model.

Take the musician Prince for example.

Every successful musician knows that the best way to build a true fan base is to begin at the concrete phase. If you go to see Prince live in concert for example, you will quickly understand why he and his music are so great.

After seeing the show, you might rush to grab the next best thing to seeing him live in order to bring back the energy and positive feelings you had while watching live. Buying albums, videos, posters and magazines are great examples of how we can listen and see Prince in our minds as if he were there in the flesh.

My call to action here is to be more Prince and think about concreteness fading during the planning process of each and every lesson. If we do this, we stand a much better chance of Making Math Moments That Matter for students.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks