What I personally didn’t enjoy was the really general “what did you wonder” questioning that I have experienced in other workshops as well. I feel like if a teacher asked me to notice and wonder, I would be annoyed knowing that it is very likely this task will have nothing to do with what I come up with, so why waste my energy? When people ask for your opinion and they don’t do anything with it, they might become resentful that you would even ask in the first place.

If the idea of “Notice and Wonder” is new to you, check out Annie Fetter from the Math Forum who has done a great job developing this idea and sharing it with the math world.

This isn’t the first time I’ve had workshop participants question the utility of asking students to notice and wonder. Sometimes, I can see a few eyes roll and every now and again I come across some who are reluctant to participate in this portion of the task. However, I feel that this portion of the lesson can often make or break a task. Let’s explore why.

Building Trust and Confidence Through Discourse

If you’ve ever been to workshops led by Jon and I, we make a significant effort to get participants talking as much as possible in non-threatening situations just as we would when working with students. For example, in this past workshop, we asked the group to think about memorable moments in their lives and the math moments they remember from their educational experience as a student in order to share with the group. Taking the time early on in a math lesson for students to talk and share their thoughts where the stakes are low can be helpful to build trust and confidence, while also showing them that we value their voice regardless of their ranking in the invisible – yet very apparent – math class hierarchy. A well led notice and wonder discussion can really go a long way to creating a classroom of discourse that will hopefully over time, develop into mathematical discourse.

Sparking Curiosity

Not only does asking students to notice and wonder give them an opportunity to have a non-threatening discussion with their peers, but it also helps to feed their natural curious mind. I will never forget the first couple of years attempting to use Dan Meyer-style 3 act math tasks in my classroom and how often I felt like the lessons were a flop. What I eventually realized was that I didn’t take enough time to spark the curiosity in my students by developing the storyline of the problem. After taking much time to reflect on what my lessons were missing, I realized that I wasn’t giving my students a reason to get excited about the task or give an opportunity to engage in any thinking until they were ready to actually solve the problem. They knew that I was going to show some sort of video or photo and I would then tell them what to do next. When we ask students to notice and wonder, we are asking them to think, discuss and share their thinking which builds more interest and anticipation for more. And while the teacher should always have a specific direction in mind for where the learning will lead, we can still make each student feel like a contributor to the class discussion and the direction of their learning by writing down their noticings and wonderings for possible extensions and for future lessons.

Notice and Wonder Challenges

That said, asking students to notice and wonder isn’t something all students will enjoy at first. Some have said they “feel silly” or that “this is stupid” likely because they aren’t accustomed to being involved in the development of a problem and thus, they aren’t quite sure what they are supposed to do. However, I think that this temporary struggle can be a good thing. One of the reasons I want students to notice and wonder when they think about mathematical situations is so they aren’t so dependent on me telling them everything they are supposed to see or do in math class. Over time, many students learn to enjoy the process however like in other areas of life, some may not. An observation I have made over time is that I often find that my “go-getter” students are the largest group of students who hold out the longest on the notice and wonder – much like workshop participants who dislike the process – because they just want to get to the point. However, if you were to watch a movie or read a book that jumps straight to the conclusion, you’d be pretty let down. We have come to expect that sort of uninspiring and emotionless experience in math class and it shouldn’t surprise me when students push back when I try to push them to get involved in the development of the problem.

Our Unconscious Bias

Something Jon and I have discussed in the past is about how most teachers would likely fit in the “go getter” category since we were likely the students who understood the game of school and specifically, how to succeed in math class. It can be easy for us to believe that all students think and feel the same way we did in the math classroom. However, the reality is that many students do not feel as comfortable or confident as many of their teachers may have when they were in math class. When our experiences learning math are very different than that of many of the students in our classroom, it is easy for us to develop an unconscious bias. This might influence our thinking around whether or not there is a need to create non-threatening opportunities for students to talk and discuss in math class.

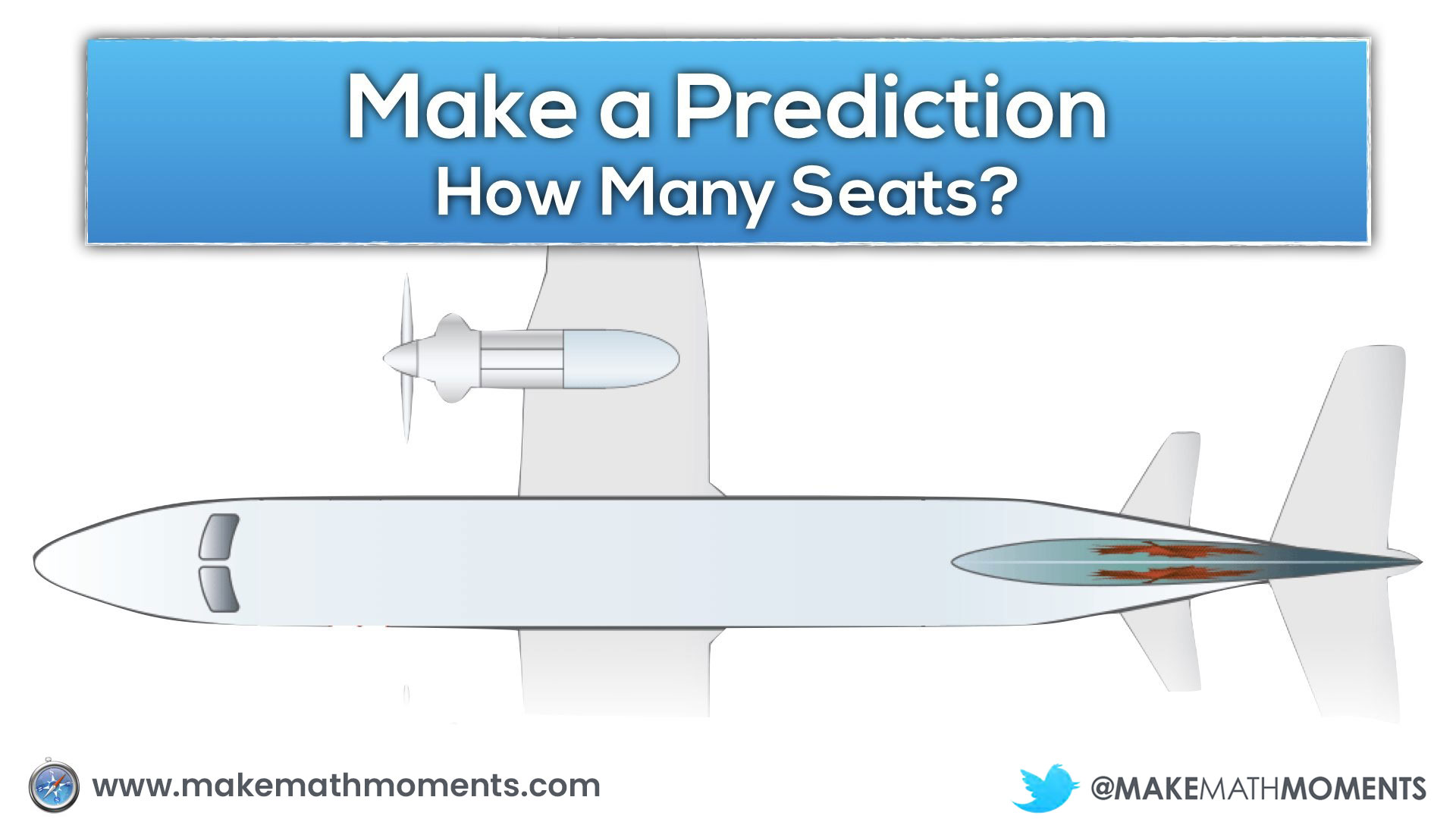

Interestingly enough, it is not uncommon for those who oppose the notice and wonder portion of a lesson to also become uncomfortable making predictions when required information is withheld. For example, if I ask a group to make a prediction about how many passenger seats there are in the plane below, some get anxious and a bit scared to throw out a prediction that may be way off despite the fact that they don’t have enough information.