Maximizing Your Return on Investment

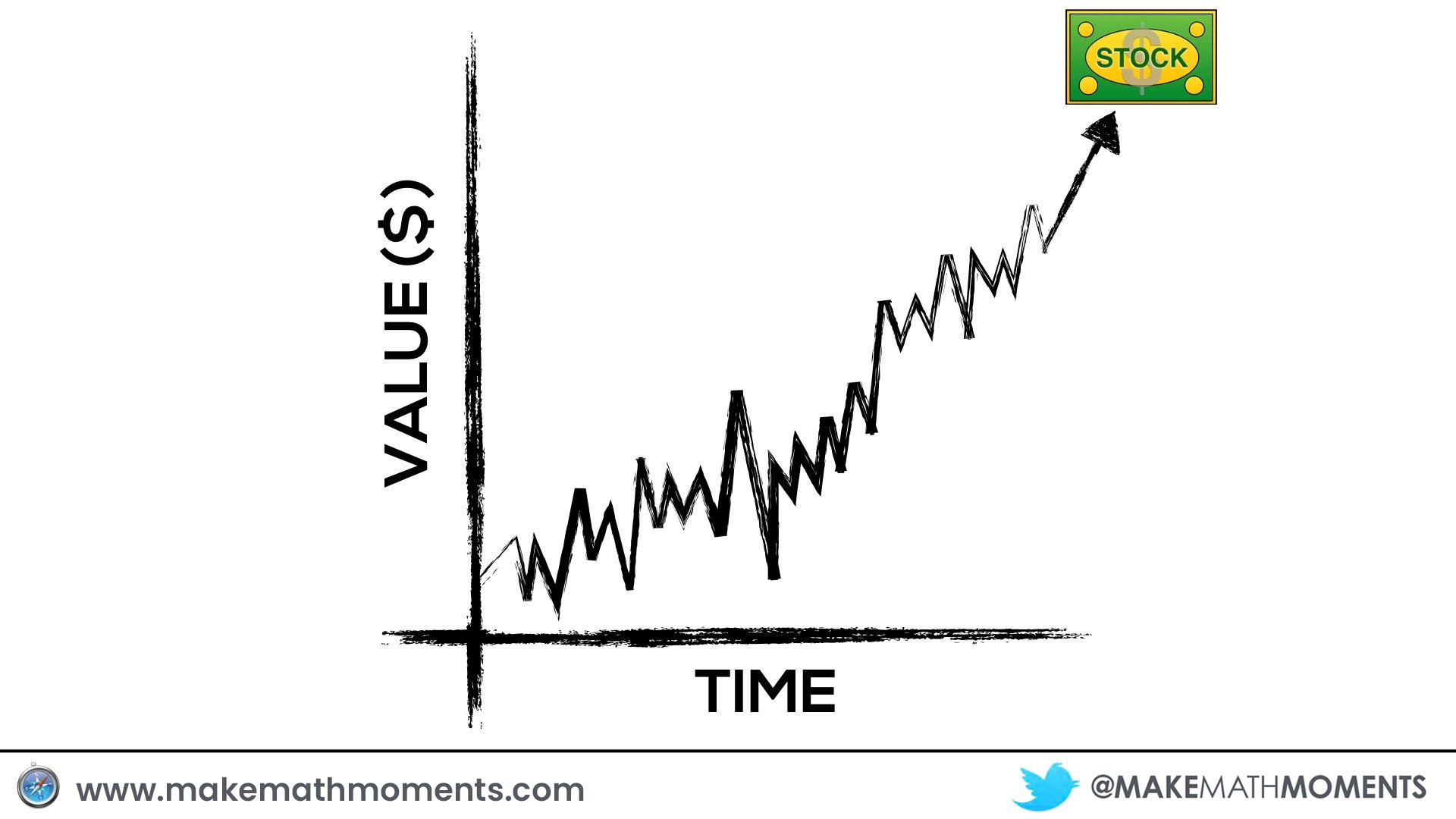

In recent months, I’ve been doing quite a bit of reading about investing in the stock market. I’ve always had an interest in finance and saving money, but I have never really had a deep understanding of how to be a successful investor beyond handing my money over to a financial advisor or picking random mutual funds. As I dug deeper into the investing world, I began to notice that some popular keys to investing seemed to mirror a reasonable approach to implementing effective teaching strategies.

Regardless of whether you feel like you are a pro-investor or a newbie, my guess is that many have at least heard the popular investing saying: “buy low, sell high!”

This concept parallels what an educator is trying to achieve when introducing a new teaching strategy in the classroom:

If I invest time and effort into a new teaching approach, then learning outcomes will improve for my students.

Despite how simple this may sound, things are rarely as easy as they seem. When investing, many are not comfortable making their own investment decisions. A similar lack of comfort is common amongst many educators when conversations about making changes to their teaching practice are explored. My hunch is that while the concept of buying low and selling high is fundamentally straightforward in both cases, determining what to buy when investing or which strategy to use when teaching becomes much more convoluted once you begin to dig in.

Which Companies/Strategies Should I Buy/Use?

If you’re thinking it can’t be that difficult to find a good company to invest in or an effective teaching strategy to use in the classroom, then you might want to think again. There are over 2,800 different companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange and over 150 teaching strategies listed on The University of North Carolina at Charlotte’s learning resource page. Don’t forget that there are a large number of stock markets around the globe and a wide range of other influences on student achievement that we may not even be aware of.

In the investing world, one could invest in Apple (APPL) at about $100 a share or Microsoft (MSFT) at $50 per share, but which is the better pick? Does Apple having a value double that of Microsoft make it a better pick or does Microsoft seem like a deal you can’t refuse?

In the learning world, a teacher could invest all of their time and effort into direct instruction or an inquiry-based approach, but may still feel uncertain as to whether or not they are maximizing learning outcomes. Is direct instruction a better teaching strategy due to the highly structured and guided approach or does inquiry-based strategies provide a better opportunity for students to construct their understanding of content?

Risk, Speculation and Gambling

Making a decision based on speculation to invest in a company or in a math teaching strategy without specific and logically sound reasoning increases risk. If we allow our decision making process to be influenced without an appropriate amount of evidence, we are ultimately taking a gamble in hope that probability will be on our side. What constitutes an appropriate amount of evidence could look very different when comparing investing and teaching. For example, I think that while many teaching strategies are research-based, there are many other strategies teachers may explore based on their own creativity and an intuition that the strategy could have positive effects on student achievement. On the other hand, some in the financial world believe that intuition can be useful to identify a good buy, but I don’t believe there are any investors claiming to make decisions without thoroughly conducting the necessary research to confirm that their thinking is more than just a hunch.

With that said, my hypothesis is that investors would be less likely to gamble on an investment based purely on intuition than an educator would on a teaching strategy because the investor has more to lose in a very short amount of time. We as educators are protected because it is almost impossible to go “all in” on a strategy and lose it all. A particular teaching strategy may yield no academic gains, but it would seem highly improbable that there are too many (any?) strategies that would cause students to actually regress or “undo” prior learning.

Changing Teacher Practice Yields Limited Risk

Despite the seemingly limited risk educators take on when exploring new teaching strategies, teacher resistance to change is common across many school districts. This seems logical since every teacher believes they are doing the best they can by using effective strategies they feel will be most beneficial to student learning. Conversely, I have never met a colleague who openly admitted to doing less than their best by intentionally using ineffective strategies to limit learning outcomes.

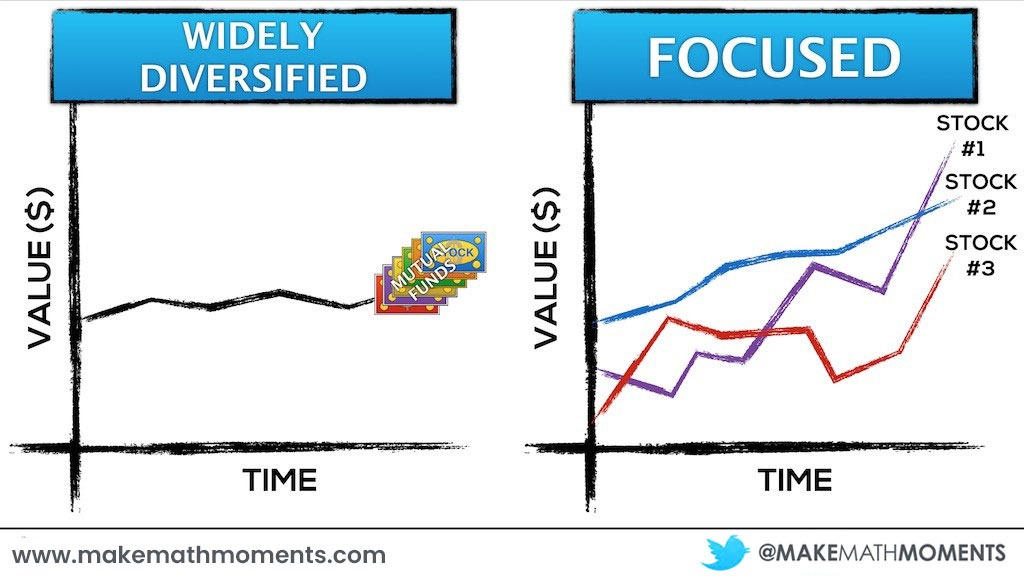

So what do education policy makers, districts, consultants and instructional coaches like myself do? We bombard teachers with a huge list of “research-based teaching strategies” to diversify the lesson delivery in classrooms. Just as an investment advisor would tell you to diversify your investment portfolio to limit risk, it would seem that we promote the same logic in education reform.

Why Do We Need Diversification?

If exploring new teaching strategies produces minimal risk, why do we need diversification?

Rather than sharing a variety of teaching strategies that educators can use at their discretion, all too often system frameworks are created with an expectation that teachers will follow specific lesson formats regardless of whether the approach aligns with their current (hopefully, ever-changing) beliefs. While research indicates the benefits of using such teaching strategies, the risks may outweigh the rewards when teachers are forced to use them against their will. To make matters worse, we often exacerbate a group of already jaded educators when we forget to celebrate the many great things they are already doing in their classrooms on a regular basis.

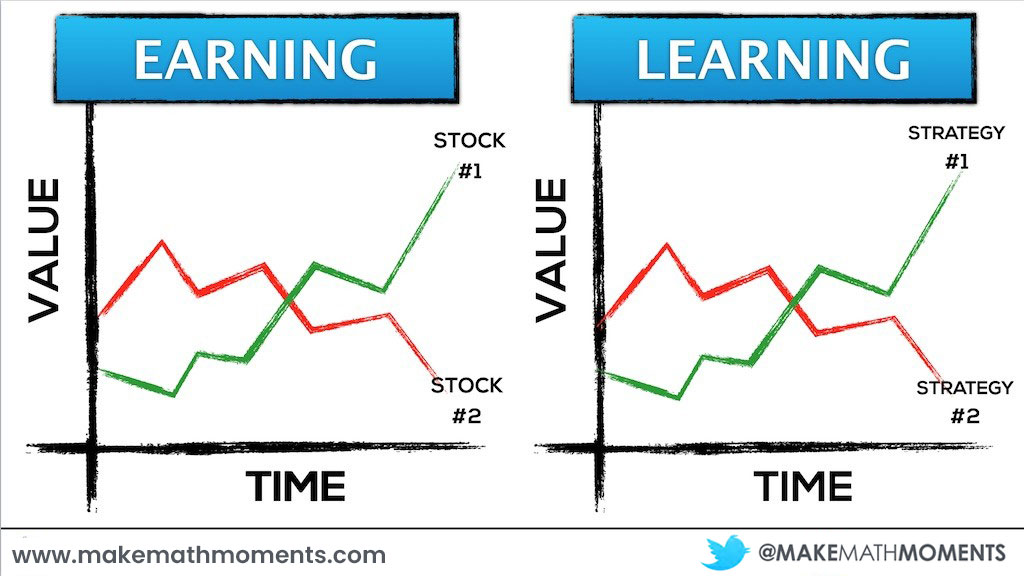

This self-induced need for wide diversification in the classroom also arises on Wall Street. The inherent need for diversification when building an investment portfolio has been rejected by some of the most successful stockholders of all time as a “recipe for mediocrity“.

Wide diversification is only required when investors do not understand what they are doing.

What Buffet and other successful investors like him advocate for is focus. Rather than investing into a large list of companies – some that will go up in value, some that will go down – do the necessary research to understand the difference and invest in only those that will maximize the return on your investment.

In Search of The Formula

While the word “formula” is probably more common to us math teachers than those in other subject areas, there is no denying the human tendency to want a simple list of steps to follow in order to achieve a desired result. Whether it is The Formula for Losing Weight, 10 Steps to Getting Noticed by Your Crush, or Five Steps to Make Your House Hunt a Happy One, people are always looking for a quick-fix to their problems. The world of finance and education are certainly not exceptions to this rule.

Unfortunately, there is no formula to getting rich or to being the best classroom teacher. If there was, we’d all be rich and our problems in education would be solved.

Fundamentals for Successful Earning and Learning

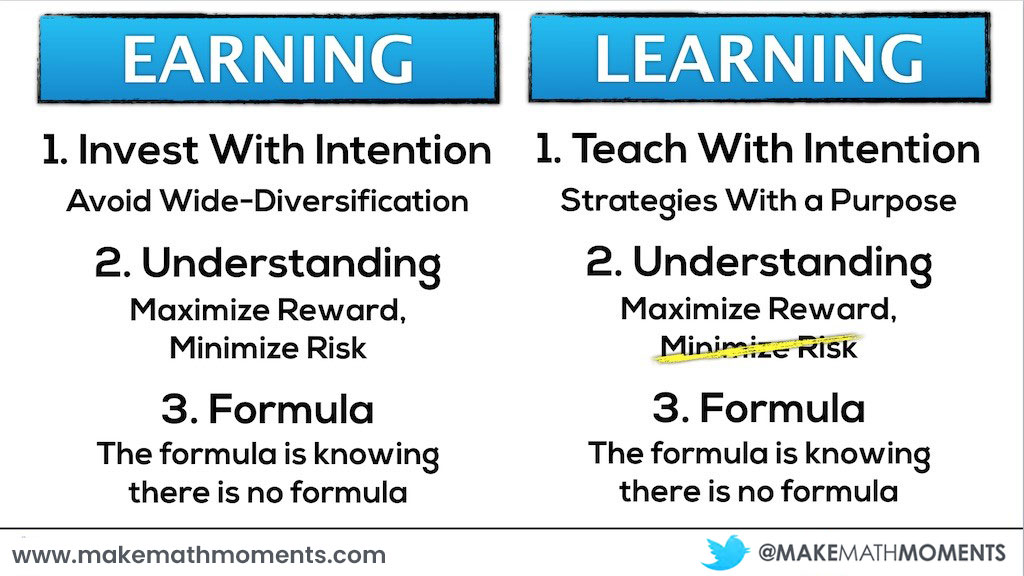

Although there is no exact formula that will lead to successful investing or teaching, we can use the following fundamentals to help guide our work:

-

Intent

Avoid widely diversifying without having specific intent or purpose for each of your selected investments/teaching strategies.

-

Understanding

The only way you can maximize reward and minimize risk is to deeply understand the investments/teaching strategies you use.

-

Formula

The formula is knowing that there is no one formula for success.