Japanese Multiplication? Chinese Multiplication? Line Multiplication?

Whatever it’s called, it’s only a trick if you simply memorize without meaning

Have you ever wondered why Japanese multiplication works?

I’ve heard some call it Chinese multiplication, multiplication from India, Vedic multiplication, stick multiplication, line multiplication and many more.

While many might argue as to the origin of this multiplication trick, I’m going to argue that it very well could have originated right here in Ontario, Canada, considering how our Ontario grade 1 to 8 math curriculum suggests we might go about teaching multiplication.

But just for the record, I really do have no idea where it came from and nor do I care. I do, however, REALLY care about WHY this method works. If you think it’s simply a trick, that’s because you’re likely considering this method from a procedural perspective alone.

Check out a full explanation in the video or read the written/visual summary right underneath.

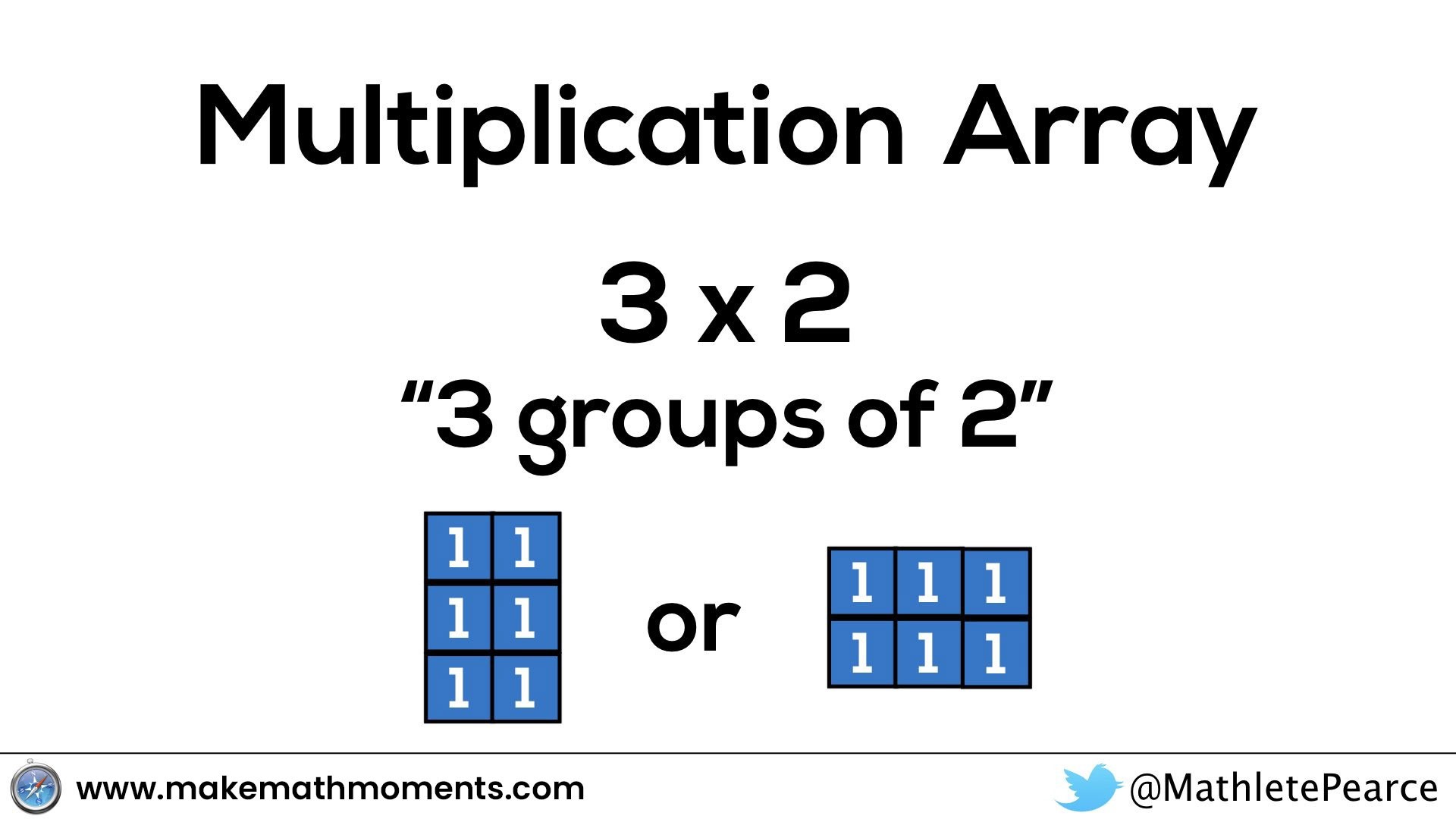

In order to understand how Japanese multiplication works, we must start back at the good old, reliable method of organizing equal groups in rows and columns. You’re right, I’m talking about an array:

When we say “3 times 2”, that is the same as saying “3 groups of 2” and we can show these three groups as 3 rows and 2 columns or 3 columns and two rows.

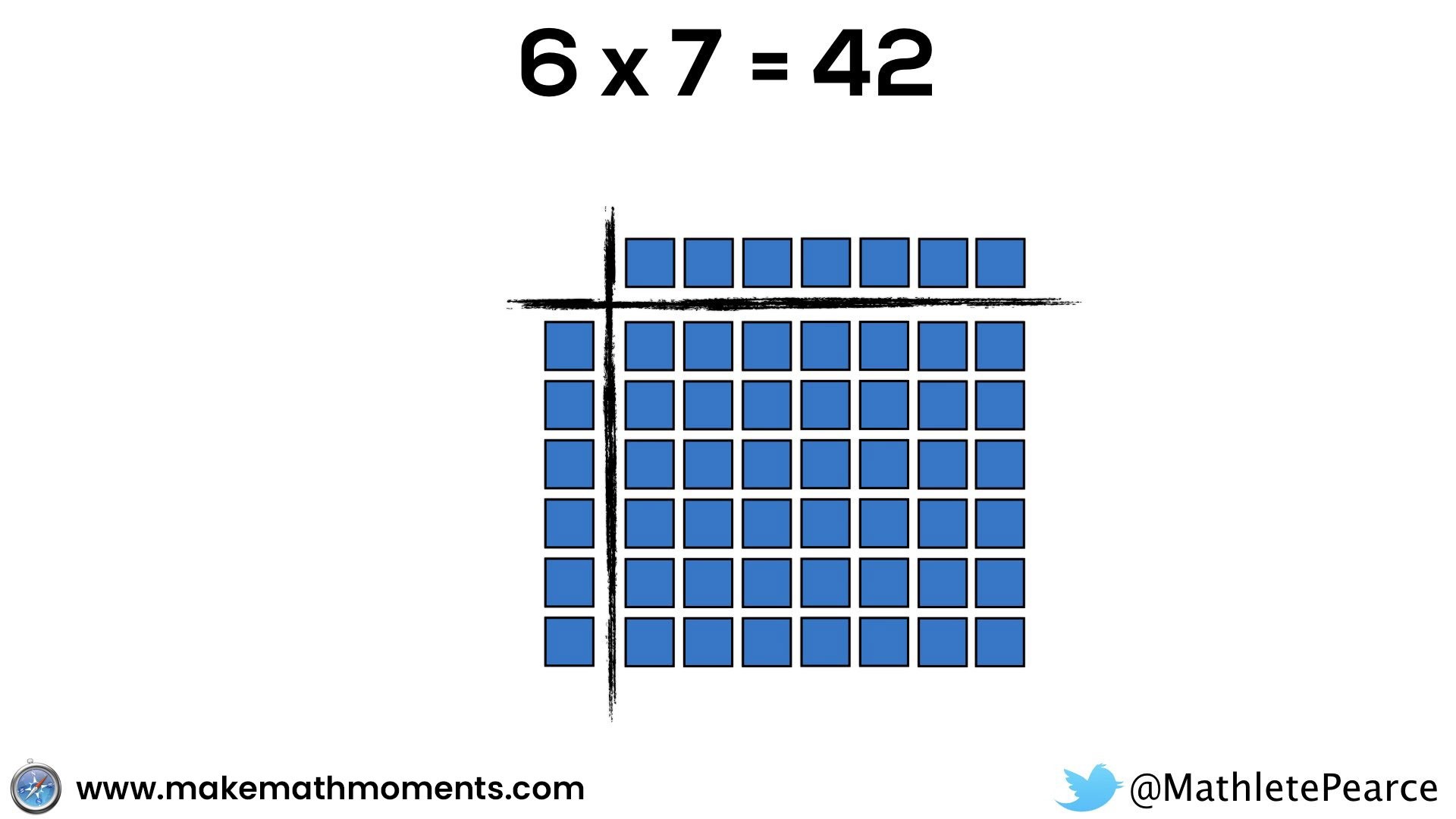

As numbers get bigger, like 6 groups of 7, it can often be helpful for students to show the number of groups and number of items in each group (also known as factors).

Note that the arrangement might look familiar as this is often how we traditionally organize our multiplication tables or multiplication charts.

While arrays are super cool, we’re not here to just discuss the benefits of using arrays when learning how to multiply. They can also help us understand why Japanese multiplication actually works.

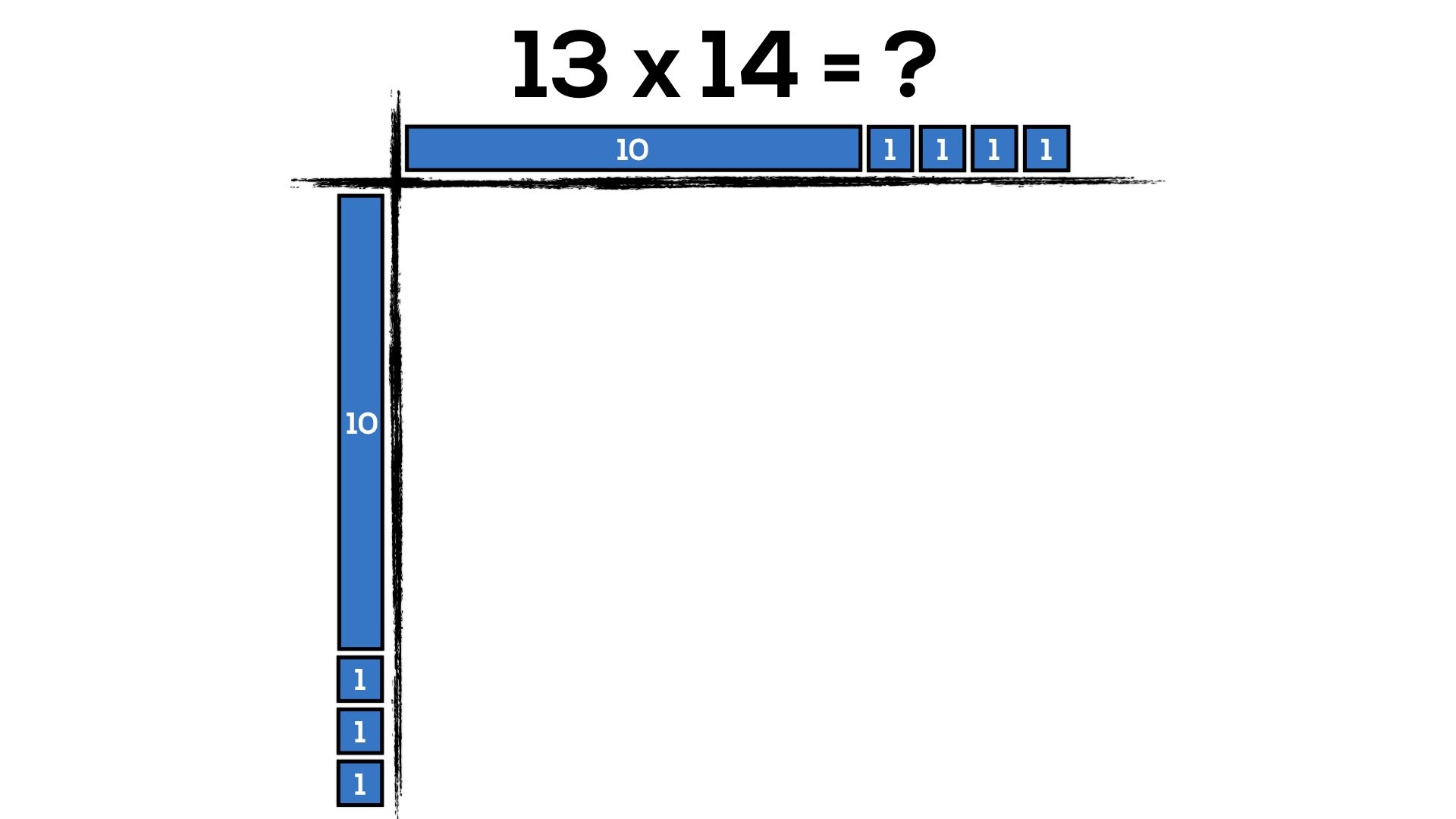

We’ll get closer to the reason when we start looking at larger factors like 13 groups of 14. But man, it would really suck if we had to build an array of 13 rows and 14 columns with individual tiles!

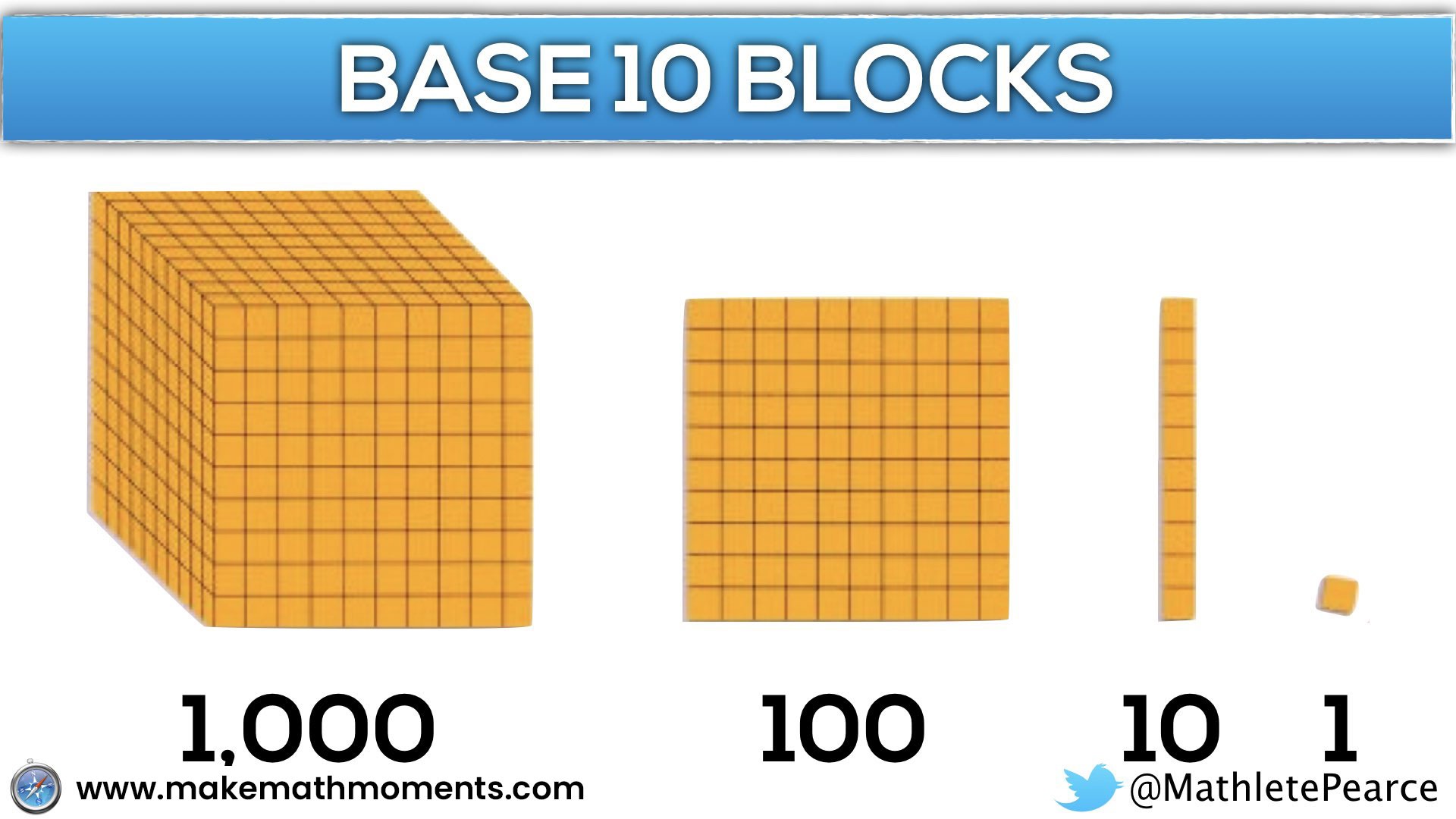

Luckily, somebody out there thought of base 10 blocks to make building arrays with large factors easier!

To build an array of 13 groups of 14, we can use base ten blocks to represent 13 as a “10-rod” plus 3 “unit tiles”. This reduces the number of manipulative pieces from 13 pieces to represent the number 13 to only 4 pieces and from 14 pieces to represent the number 14 to only 5 pieces.

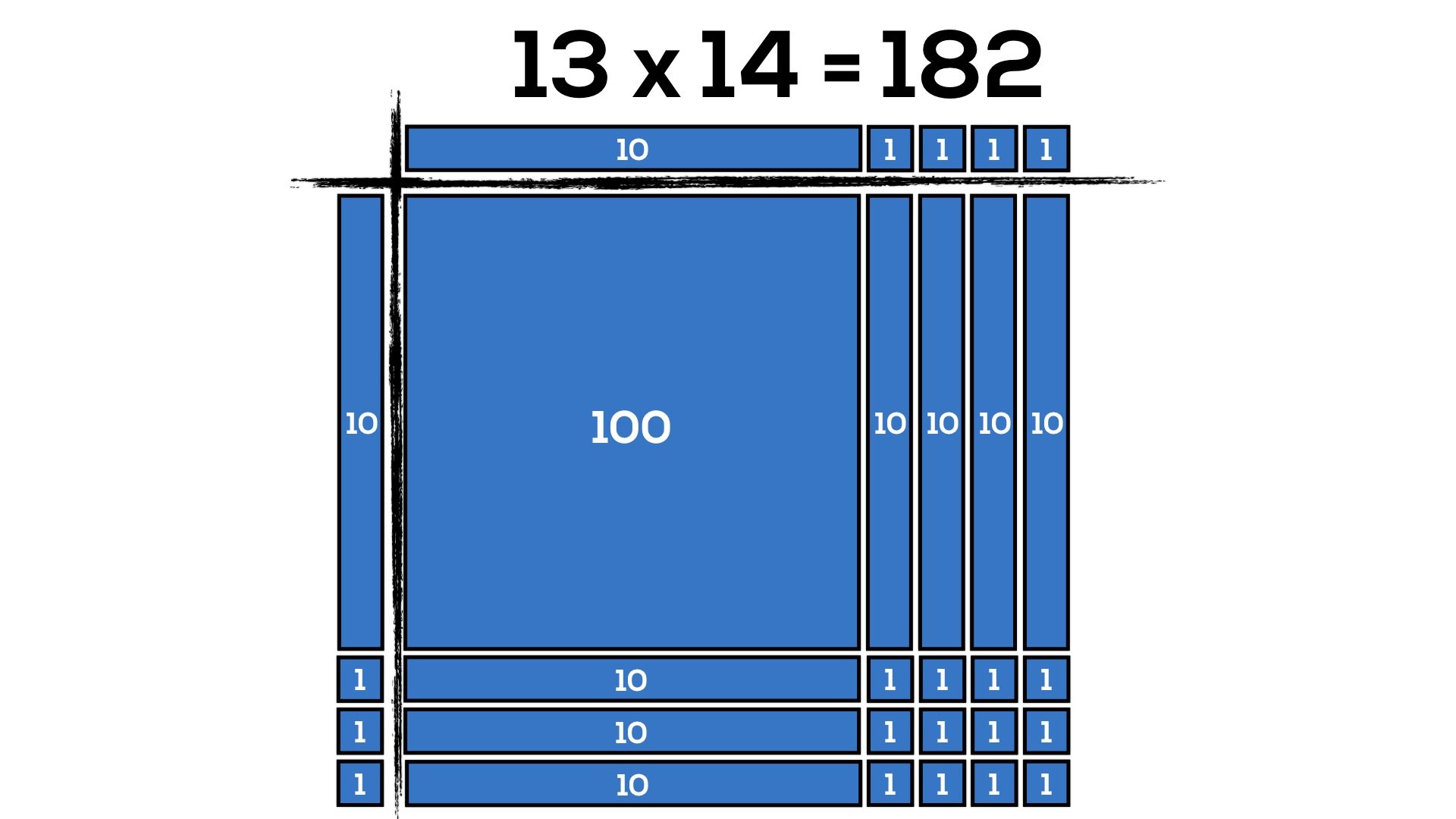

Now, we can multiply in parts, focusing first on our 10 rods.

Just like you would with a multiplication table, we can multiply 10 times 10 and see that the space the product occupies is 100. With base ten blocks, we can use a “100 flat” instead of 100 individual units, or 10 ten-rods.

Then, we can look at the empty space in the top right of our array and note that we now have to multiply 10 (from the factor of 13) by the remaining 4 units (from the factor of 14) to get 4 ten-rods, or 40.

Repeating the same logic for the remaining 3 units form the factor of 13, we then multiply 3 by the ten-rod to get 3 ten-rods or 30.

Finally, we multiply 3 units by 4 units to get 12 for a final product of 182.

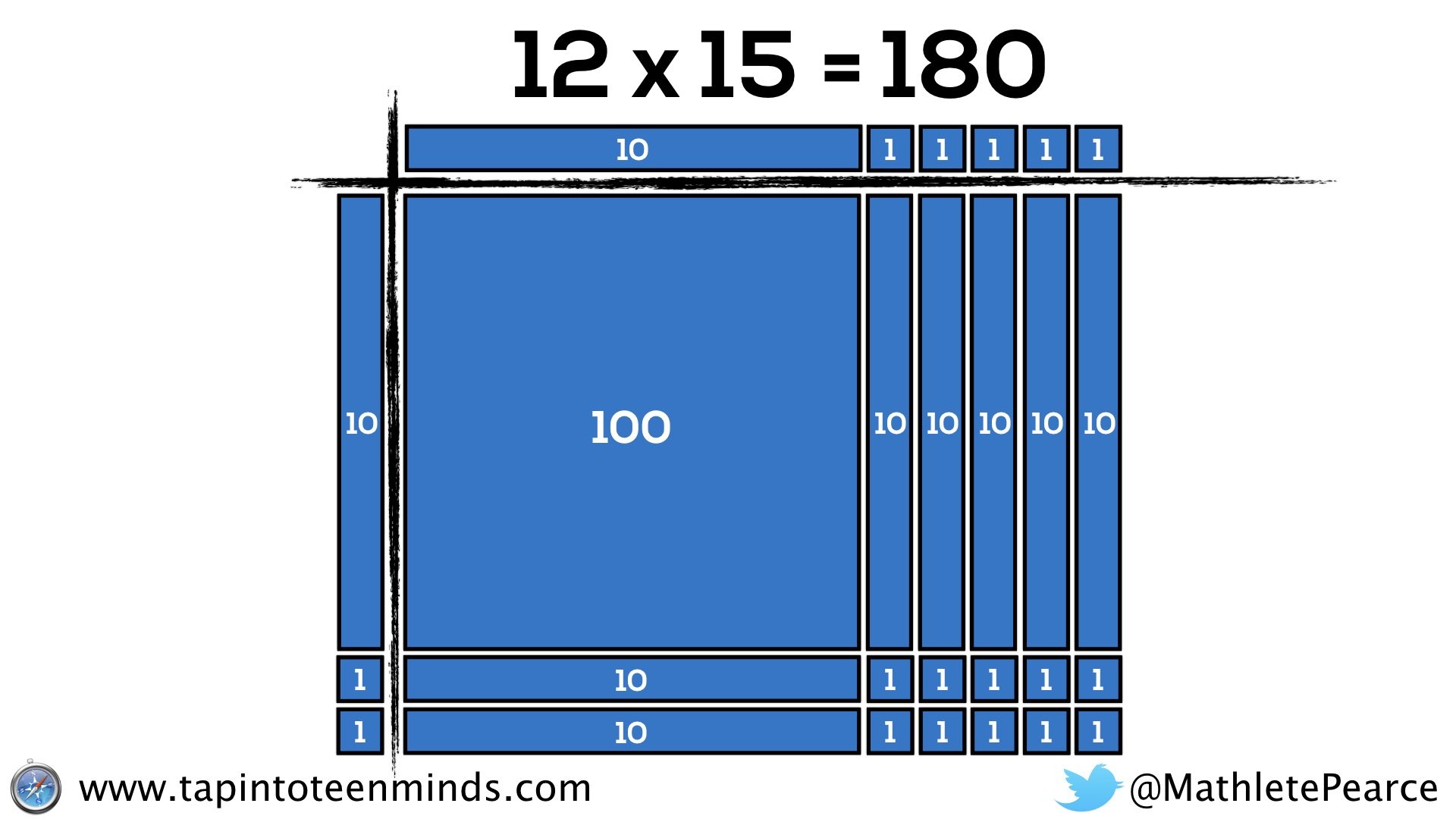

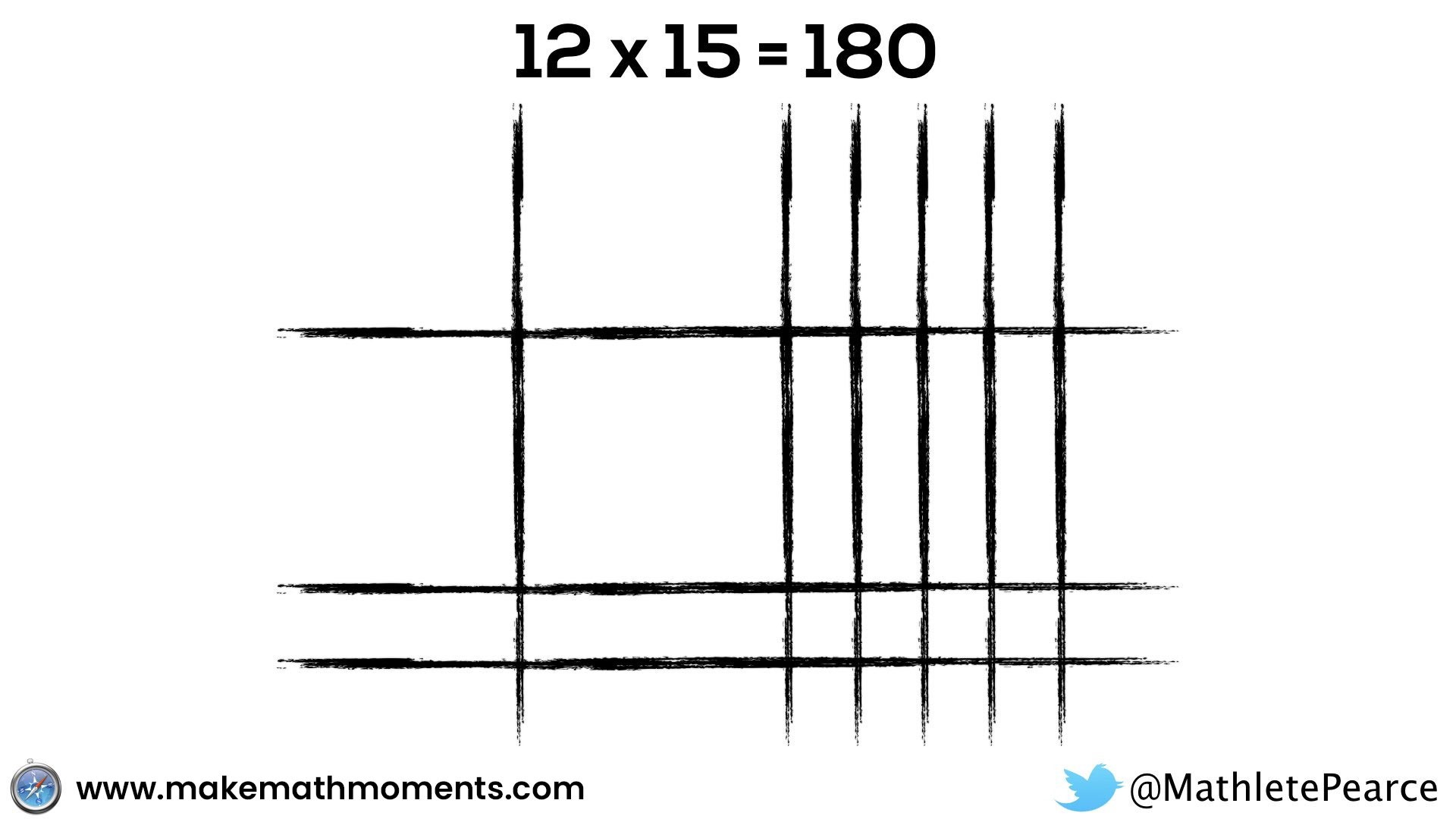

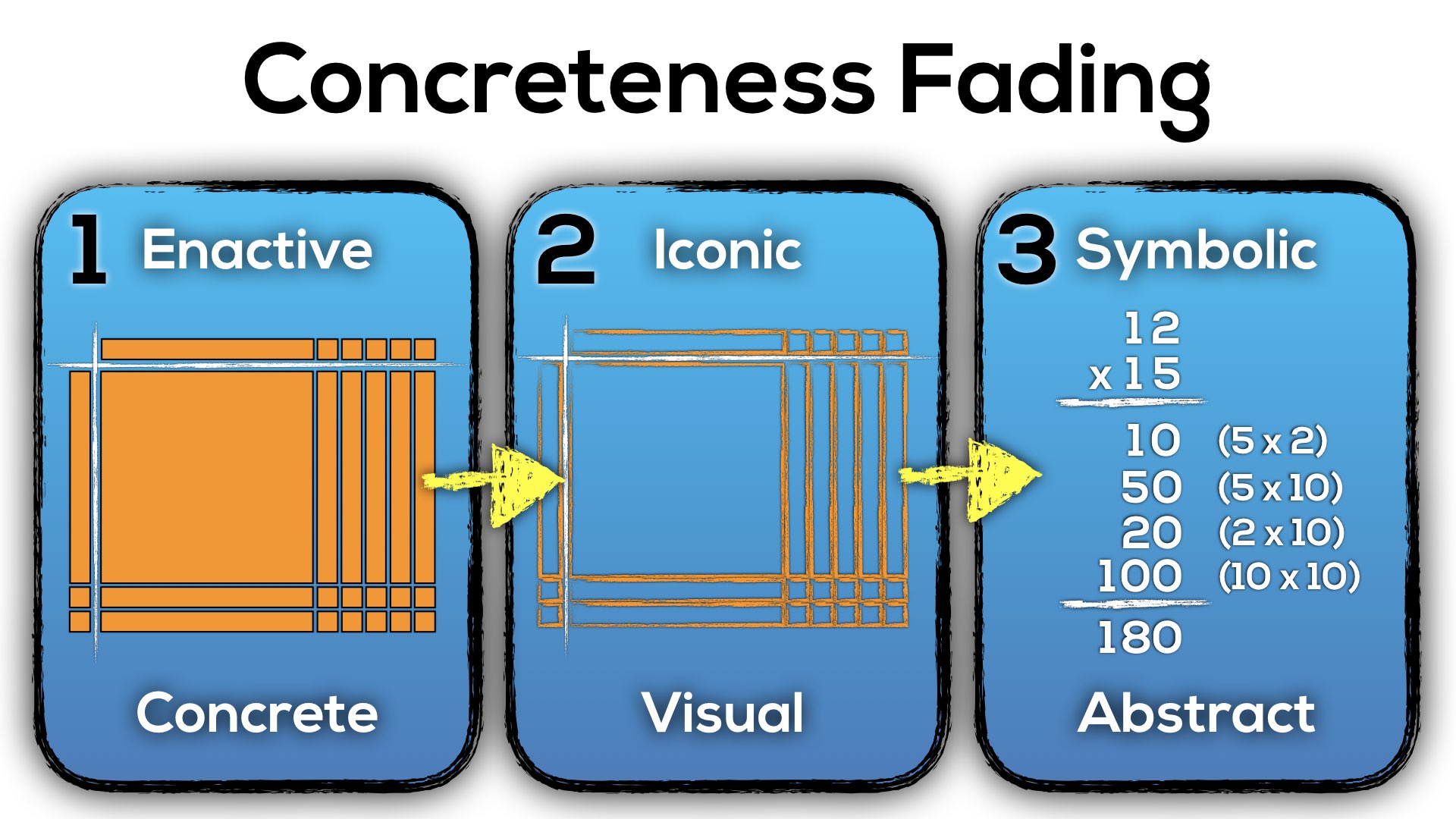

This time, we’ll look at 12 x 15. Notice that the same logic applies:

Now, let’s make the connection to the Japanese multiplication method.

I’m going to hide the values of the base 10 blocks in order to clean up the screen and get rid of the clutter. Now, I’m going to highlight the “gaps” between each base ten block piece with lines (see where this is going?):

Moving forward, I will separate our factors from the array a little bit more so we don’t get confused. As you’ll see below, the Japanese multiplication is simply skipping the step of drawing out the base 10 blocks by having you focus on the intersection of the base 10 blocks (or the sticks / lines). As you can see in the animated gif below, each base ten block is replaced by the intersection of the lines situated between each base ten block:

- In the top left corner, we have a ten-rod multiplied by a ten-rod to give 100. Notice it is the intersection point of the two ten rods that represents the 100 flat.

- In the top right corner, we have 5 units multiplied with a ten-rod to give 5 ten-rods or 5 intersection points to represent 50.

- In the bottom left corner, we have a ten-rod multiplied by 2 units to give 2 ten-rods or 2 intersection points to represent 20.

- Finally, in the bottom right corner, we have 5 units multiplied by 2 units to give 10 units or 10 intersection points.

Looking at both the array with base ten blocks or Japanese multiplication, both methods are automatically chunking our factors of 12 and 15 to make use of the distributive property; 12 = 10 + 2 and 15 = 10 + 5.

Now that you’ve had a chance to experience using base ten blocks through this post or more in-depth here, you can probably visualize the base ten blocks sitting between the lines that are used in the Japanese multiplication method.

Pretty cool, eh?

Japanese Multiplication Is Only a Trick If You Don’t Know Why It Works!

I’ve seen a bunch of posts floating around social media suggesting that Japanese multiplication is a multiplication trick or some sort of “magic” or “voodo trick“. This statement is only true if you never seek out to understand why it works. While I’ve taught many math tricks such as cross multiplying for solving proportions and sum and product for factoring in the past, these past few years I have completely abandoned this approach from my teaching. I have to be careful here because I’m not suggesting that cross multiplication or sum and product are bad methods to use in math; it is more about when and how they come about in math class.

Developing a Deep Conceptual Understanding Will Lead to Procedural Fluency

It is my belief that there is no such thing as a “trick” in math class when a deep conceptual understanding is constructed prior to introducing procedural fluency. In the case of solving proportions, students should be able to solve a proportion using opposite operations and their understanding that the equivalent relational quantities are multiples of each other. Understanding “how many times bigger” one “piece” of a fraction is than another is very important prior to simply giving students a tool like cross multiplication to simply “get to an answer” as fast as possible. I’d like to think that if students have built a deep conceptual understanding prior to moving towards procedures and algorithms, it is likely that they will better understand how to use the procedure efficiently and will also be able to get themselves out of a jam if troubles ever arise.

In the case of Japanese multiplication, I would argue that it is only a multiplication trick if you are teaching this method without students having had the opportunity to work with the conceptual underpinnings that make it work flawlessly. In particular, students should have the opportunity to spend a significant amount of time working with concrete materials like square tiles and base ten blocks to build arrays in order to build strong multiplication fluency prior to pushing students to an iconic or visual representation like drawing the base ten blocks or using a more abstract representation like drawing intersecting lines.

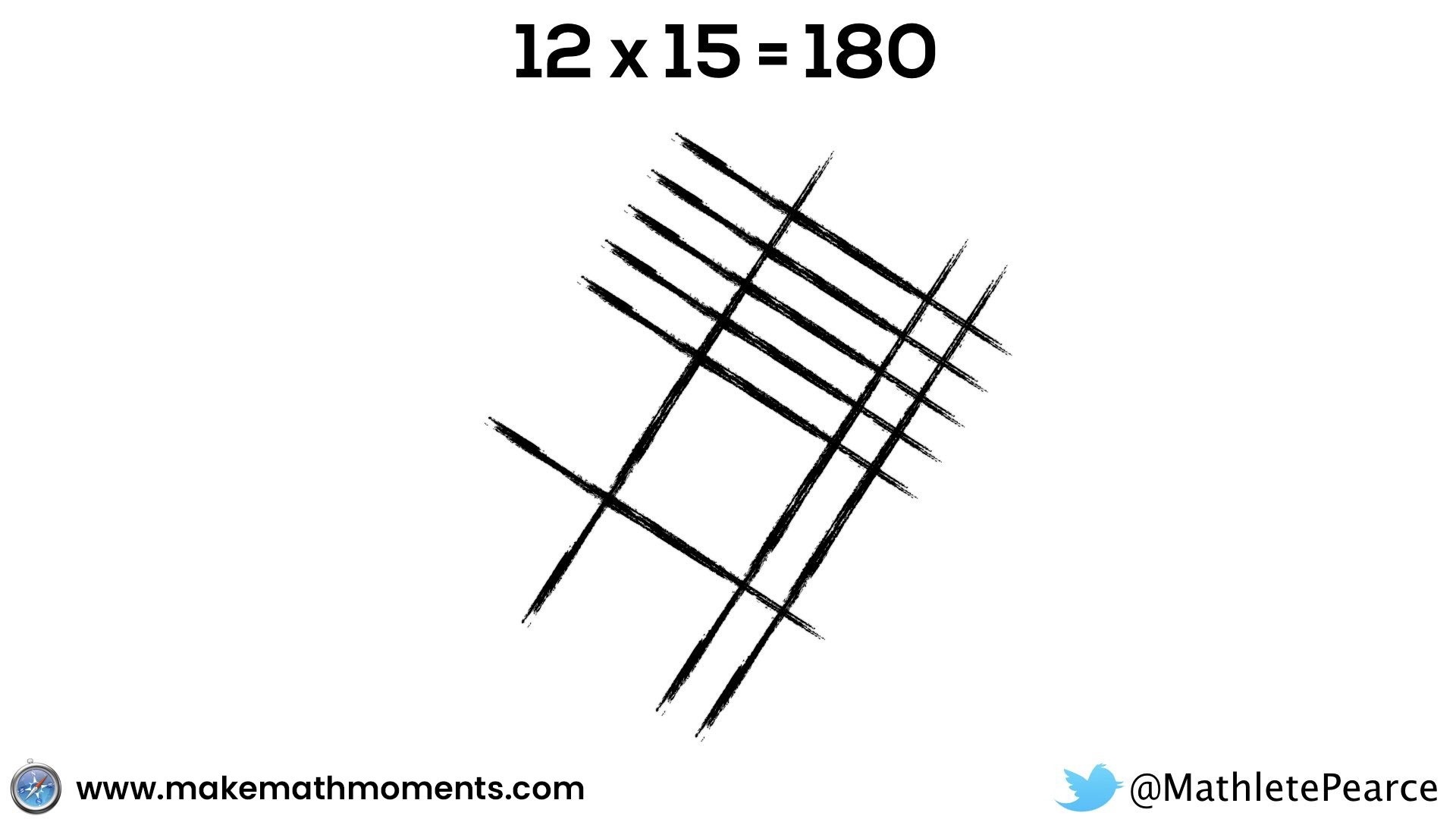

Japanese Multiplication: Why Diagonal Lines?

You might be asking yourself:

Why do I always see the lines in the Japanese multiplication method on a diagonal?

By showing the lines diagonally, the base ten block array now organizes the intersection points in order of place value. Have a look below:

As you can see above, an opportunity to circle back to place value and the importance of understanding that in base ten, we cannot have any number greater than 9 in any place value column. You’ll notice that the 10 one’s must be swapped out for a ten rod.

So while many might consider this to be a pretty cool “trick”, it is much more powerful if students can articulate where procedures like these come from and why they work.

Better yet, after students have a thorough understanding of arrays with base ten blocks, I’d much rather challenge them to see if they could come up with an easier way to visually represent their two-digit multiplication on paper without having to draw a bunch of rectangles and squares. Some might use sticks for base ten blocks and maybe, just maybe, someone in your class might come up with something similar to this stick method. How cool would that be?

Base Ten Block Arrays & Japanese Multiplication IS the Standard Algorithm

Oh, and before you go, you should know that using base ten blocks or the Japanese multiplication method is a great way to explain why partial products and the standard algorithm for multiplication works.

If we have a look at the array and the standard algorithm, side by side we can clearly see each step of the algorithm. Check it out:

If you’re interested in more about how arrays, area models and the standard algorithm connect, see this post.

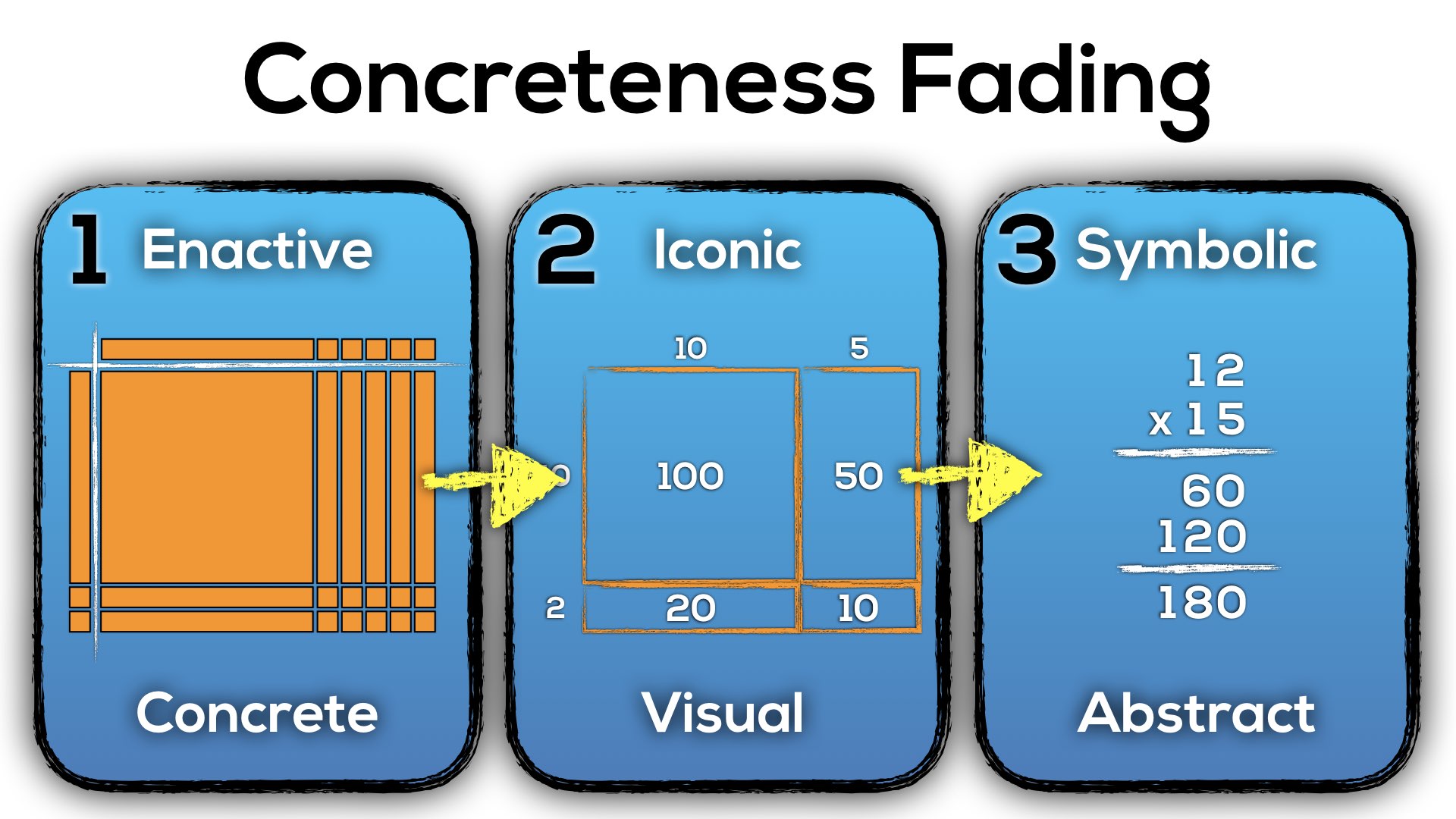

The Importance of Concreteness Fading in Mathematics

Concreteness fading is a theory suggesting that mathematical concepts are best learned in three stages; the enactive stage, where students use concrete manipulatives that represent the mathematical concept they are working on.

Over time, after students have had enough experience physically working with the concrete manipulatives, they move to the iconic stage, where they begin to (often naturally) draw a visual representation of the concrete manipulative instead of having to physically hold and manipulate the object in their hands.

As students become increasingly comfortable with the iconic or visual representations, does it make sense for them to begin using symbols that represent the meaning behind the previous visual and concrete representations. This stage is thought to be the most abstract of the three stages because now numbers and symbols are used as a more efficient way to represent the work and experiences that have been developed in the previous stages.

The Japanese Multiplication Method and Concreteness Fading

So what does the multiplication we just explored today look like relative to the three stages of concreteness fading?

Concreteness Fading: One-Digit by One-Digit Multiplcation

When it comes to single digit by single digit multiplication using individual unit tiles as we did at the beginning of this post, the stages might look like this:

- Enactive/Concrete: Physically arranging square tiles into an array.

- Iconic/Visual: Drawing squares or dots in an array on paper or using spatial reasoning to visualize the array in your “mind’s eye”.

- Symbolic/Abstract: Using numbers and symbols to represent your thinking, with the hope that you can visualize what those symbols mean in your mind.

Concreteness Fading: One- or Two-Digit by Two-Digit Multiplcation

As we move to two digit by one digit or two digit by two digit multiplication, the stages of concreteness fading might look like this:

- Enactive/Concrete: Using physical base ten blocks to create arrays and over time, possibly moving towards free virtual manipulatives like Number Pieces by the math learning centre, the Ontario Ministry of Education’s Mathies Colour Tiles app or the interactive manipulatives offered through the free Knowledgehook Gameshow tool.

- Iconic/Visual: Drawing the array using a base 10 configuration on paper and/or visualizing in their mind.

- Symbolic/Abstract: Connecting the concrete and visual to symbolic notation such as this “conceptual” multiplication algorithm (or “partial products”).

Another possibility might include different visual and symbolic representations such as this:

- Enactive/Concrete: Using physical base ten blocks to create arrays.

- Iconic/Visual: Drawing an area model on paper to show partial products and/or visualizing in their mind.

- Symbolic/Abstract: Connecting the concrete and visual to symbolic notation such as the standard algorithm for multiplication.

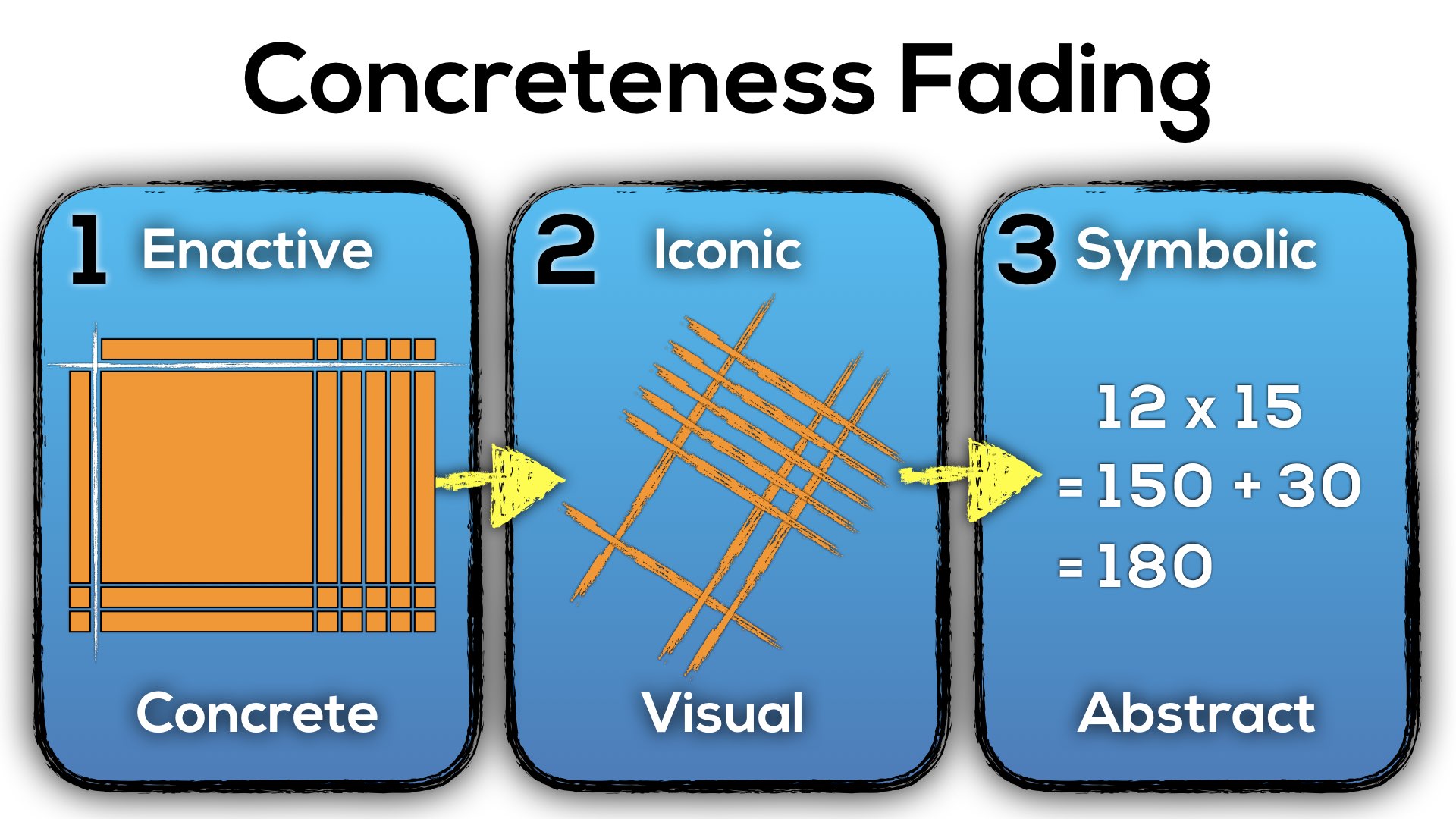

Finally, another possibility might be:

- Enactive/Concrete: Using physical base ten blocks to create arrays.

- Iconic/Visual: Drawing a modification of a base ten block array using the Japanese multiplication method on paper and/or visualizing in their mind.

- Symbolic/Abstract: Connecting the concrete and visual to symbolic notation by using mental math strategies like decomposing and re-composing numbers. In this case, mentally using the distributive property to multiply 10 by 15 and then 2 by 15.

While my initial intent with this video and post was a quick animation to show how the Japanese multiplication method really isn’t a trick, but rather a simplification of what we are asked to do in the Ontario mathematics curriculum, it blew up into a monster. I hope the time and effort spent at least has you thinking about how we might work to deepen our student understanding of multiplication in conjunction with Concreteness Fading.

I strongly believe that as we are exposed to more ways to represent concepts in mathematics, our understanding of those concepts will continue to deepen and produce more and more connections over time. I am living proof that this is true, because I am shocked routinely at the new connections that seem to present themselves to me with less and less effort with each passing day. Let’s all keep an open stance to learning and continue to build more and more connections in mathematics that we can leverage as tools in our classrooms to address student learning needs.

Do you know any other interesting ways to multiply? Please share some more (links welcome, also) in the comments for others to enjoy!