Share & Help Create More Math Moments

In this post, I want to dive into the math wars and try to clear up some confusion that may exist.

Importance of Math Facts

When addressing the math wars, I think it is really important for us to clear up some of the confusion that may exist around the importance of “math facts” or “multiplication tables” and whether students should be memorizing them.

In Canada, the media often paints a picture as though there is one group fighting for students to memorize math facts like multiplication tables – often referred to as “the back to basics” group and the other group – often referred to as the “discovery math group” is promoted as a group that doesn’t believe that math facts have any importance. Sadly, the picture portrayed in the media is incomplete at best.

And unfortunately, after the debate finally quiets down in the media for a while, it is brought right back to the forefront when standardized test scores or international math rankings such as PISA scores are released.

Regardless of whether your beliefs align more closely with a “back to basics” or “discovery and inquiry” viewpoint, the fact is that we all want students to know their math facts. The real conflict exists in different interpretations of what that means and how we can help students get there.

So, let’s spend a few minutes to better understand the similarities and differences of the two stances that are often portrayed in the media in order to find some sort of balance between both.

“Regardless of whether your beliefs align more closely with a ‘back to basics’ or ‘discovery and inquiry’ viewpoint, the fact is that we all want students to know their math facts. The real conflict exists in different interpretations of what that means and how we can help students get there.”

Memorization vs. Automaticity

One of the big differences I see between those who tend to side with the “back to basics” group and those who align more closely with the “inquiry and discovery” group is that of memorization versus automaticity.

When many think of the word memorization, they think about rote learning; committing information to memory through repetition, speed and without the need for meaning.

While humans memorize a lot of information by rote, this memorization technique is used optimally for memorizing information that is difficult to connect to other information we already know such as memorizing the address or phone number of a family member, Learning new information that can easily connect to our prior knowledge through rote can be truly limiting that new learning for recall purposes only, rather than for understanding.

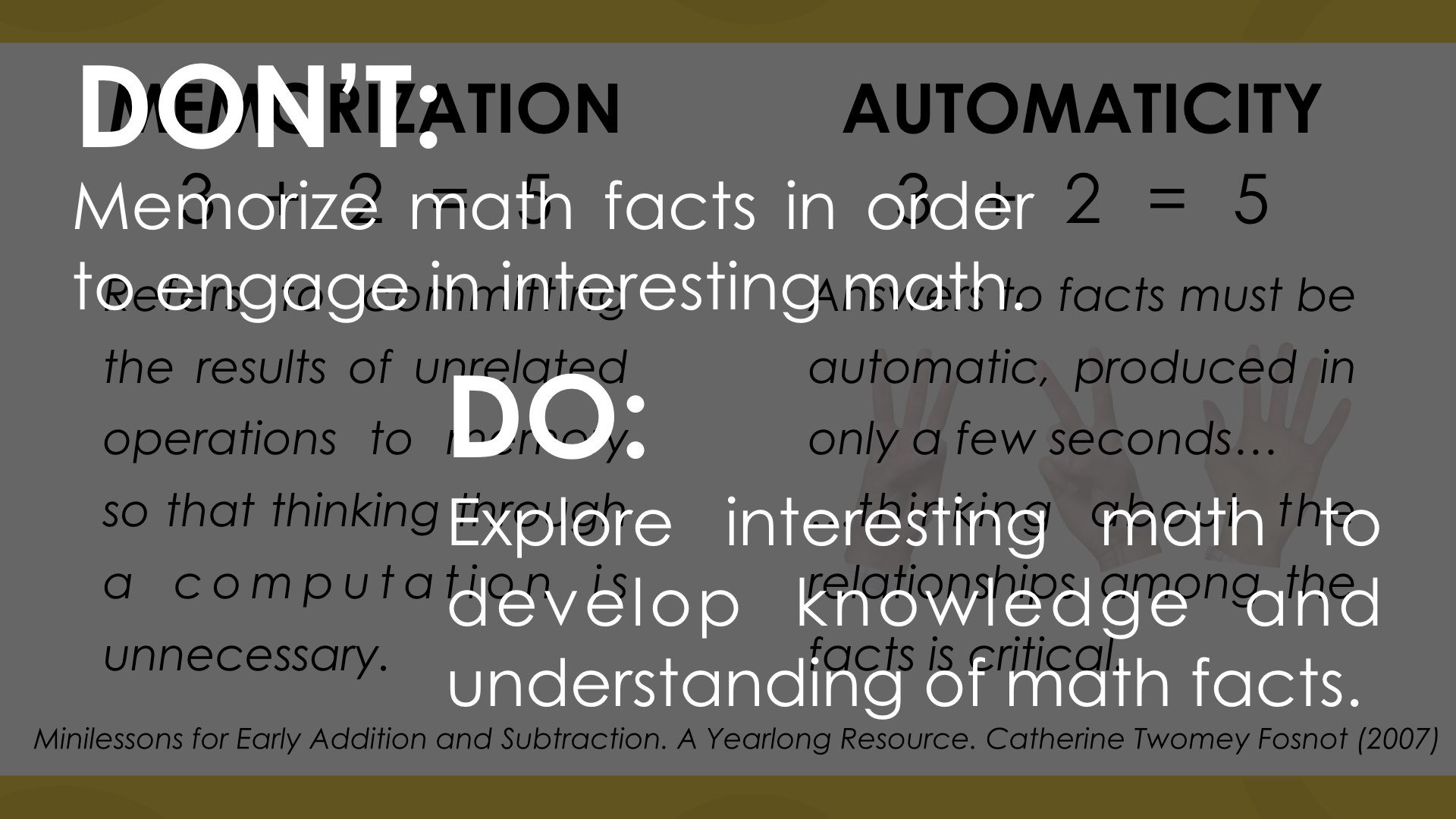

By promoting the learning of math facts and mathematics in general through purposeful mathematical experiences, students are not only able to recall their new learning, but they can also do so with understanding. This approach to learning math facts is often referred to as automaticity.

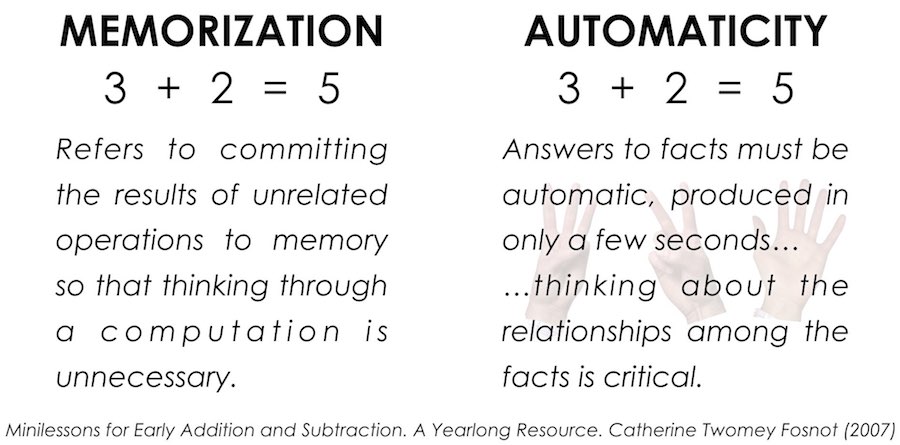

While different people may have slightly different definitions, I really like how Cathy Fosnot describes both memorization and automaticity in her Minilessons series. Fosnot states that memorization “…refers to committing the results of unrelated operations to memory so that thinking through a computation is unnecessary” while automaticity suggests that “answers to facts must be automatic, produced in only a few seconds … thinking about the relationships among the facts is critical”.

Share & Help Create More Math Moments

Hi. I am looking for ways to familiarize students with numbers, quantities and basic arithmetic. I’m working with students from sixth grade to ninth grade. There are surprisingly many students who are not able to recall or recalculate basic arithmetic and must rely on a calculator, a table or counting. Many of these students are intelligent and can easily recall other facts and reason well and many can even solve algebra problems quite readily. But there seems to be no memory for numbers which I want to say appears to me that these students have no internal model for numbers and quantities. I do not know how to help them.

Use cuisenaire rods or multilink cubes to lead children through the combinations of numbers that make larger numbers and in older students smaller numbers or negative numbers with zero pairings.