Episode #388: How to Lead Math PD Without False Authority

LISTEN NOW HERE…

WATCH NOW…

In this episode, we reflect on a challenge many math leaders face: the risk of presenting ourselves with false authority. Whether we’re facilitating professional learning, supporting instructional coaches, or engaging in school- or district-wide math conversations, strong convictions can easily be mistaken for certainty.

But leading meaningful change in mathematics education requires something different—humility, curiosity, and a deep commitment to learning. We unpack what it means to hold space for growth (both for ourselves and those we support), how to notice when we may be signaling certainty instead of inquiry, and why leading in math from a place of openness—not ego—is essential.

This is a reflective episode for anyone striving to lead math learning more authentically and build a culture where mathematical thinking, risk-taking, and professional growth are safe, shared, and ongoing.

In this episode, you’ll discover:

- Why presenting with false authority can unintentionally shut down curiosity and collaboration

- How to lead from a place of learning, not knowing

- Practical ways to model humility and openness in your leadership

- The difference between strong conviction and rigid certainty

- Why reflecting on your privilege and positional power deepens your impact as a math leader

Attention District Math Leaders:

Not sure what matters most when designing math improvement plans? Take this assessment and get a free customized report: https://makemathmoments.com/grow/

Ready to design your math improvement plan with guidance, support and using structure? Learn how to follow our 4 stage process. https://growyourmathprogram.com

Looking to supplement your curriculum with problem based lessons and units? Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons & Units

Be Our Next Podcast Guest!

Join as an Interview Guest or on a Mentoring Moment Call

Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

Book a Mentoring Moment Coaching Call

Are You an Official Math Moment Maker?

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Yvette Lehman: All right, in today’s episode, this is really just a chance for us to reflect about our own leadership in the last little bit. We had a conversation amongst our team recently about my apprehension, sometimes in this space of math leadership, of walking into different rooms and having a false authority on topics that maybe I shouldn’t be saying with so much certainty.

Jon Orr: Hmm. Tell me about like more about false authority first. Let’s like, let’s go there and then we can kind of unpack this because, you know, I think you may be downgrading in a way the in a way the authority that you have because you’ve done a lot of learning in a lot of different areas that say maybe other educators specifically haven’t. So you might be like, I just don’t have authority. But I mean, like you, you do. So like, let’s unpack like What do you mean by false authority?

Yvette Lehman: I maybe to your point, it’s that because I have engaged in this learning and I do see myself as a math leader, I worry about the influence that I have because I’m the type of person, and you say this all the time, John, I have really strong, and Kyle, you know this too, I have very strong convictions. I feel very strongly about the things that I believe, but I’m also an aggressive learner.

And so those strong convictions are constantly, they’re loosely held. They’re loosely, right, they’re loosely held. I feel like I’m constantly learning and striving to be better and different. And so I worry sometimes that what I believe today, I’m gonna walk into a room, I’m gonna share my thinking, it’s going to have so much weight in that room, but then a week from now, I’m gonna feel differently.

Jon Orr: They’re loosely held? Or they’re strongly held? They’re strongly held until they’re not.

Kyle Pearce: Well, it’s funny because it’s like a vicious cycle, right? And John, kind of what you were getting at, it’s like a short term versus medium or long term. Like short term, very convicted, and very tightly held and very firmly held beliefs. But then when we zoom out to like a medium or a longer term view, you’re going, actually they were pretty loosely held because once I learned more, so you went continued down the rabbit hole and you learned something new, you then recognize that.

either it was incomplete or I still believe that, but maybe not in that one scenario because that one scenario wasn’t considering this. And I think this is one of the most challenging, not just education. doesn’t any, any part of life all really revolves around this, whether you choose to be a learner and continue to grow or whether you’re willing to sort of like die on that Hill, assuming that you’ve arrived and that you’ve learned at all. And I think

Which event do I want? I want the current event. But I think really what we’re hoping to get into in this conversation is sort of like, how do we have that strong conviction with the big asterisk there that says,

Jon Orr: I was gonna say that, Yvette is kind of saying, I really believe this right now and if I’m asked my opinion or if I’m leading a PD session or if I’m engaging other and I’m coaching other educators or I’m coaching other leaders in work that they have to go ahead and do, it’s almost like I think what you’re saying, Yvette, is like, I really wish if I could rewind time to a lot of these instances where I spoke very, very, you know.

with a lot of authority, but also a lot of conviction about certain ideas, you almost want to go back and go, disclaimer, I reserved the right to change my opinion tomorrow or a year from now. And it’s almost like every time you say something in those environments, you’re like, disclaimer, and then like every time because because you feel like I’m on this path. So it’s kind of like these are the things I’m thinking about now. But these are the things that are backed by my learning.

in my experience that either are working in this way, but then it’s like, but it could change. So take that with, you know, the grain of salt that it actually is. Is that fair to say?

Yvette Lehman: For sure. I’m going to share an example that’s been eating me up inside for the last week. And then I’m also going to talk, I guess we can unpack my reflection about what I’m going to do different the next time I’m in this situation. Okay. So I was with a group of educators last week and we were diving into the content. One of my favorite ways to spend time with educators. And we were looking at subtraction structures and we were looking at, you know, the fact that often subtraction is

Yvette Lehman: know, narrowly defined as takeaway, but in reality comparison is such a strong behavior of subtraction, but they are experientially different. Okay, so picture me, Kyle, you’ve seen this, I’m at the whiteboard.

Kyle Pearce: I’ve been there in the background nodding, you know, like going like, yeah, I like this. I feel this.

Yvette Lehman: I’m at the whiteboard and I’m talking about the different, the experiential difference between takeaway and comparison subtraction. And I’m presenting it in a very passionate way, but I’m doing a lot of the talking. So picture me, I’m at the whiteboard and I’m drawing diagrams and I make this statement that is actually false. But in the moment, no, I believed it in the moment.

Jon Orr: just in the heat of the moment, you’re like, I’m just gonna make something up. Okay, what’s the statement?

Yvette Lehman: In the moment, I made a statement that when you’re doing comparison subtraction, you often have two different attributes. So it’s like you’re comparing blue and red. You’re comparing my money and Kyle’s money. And although the units might be the same, there’s something about it that distinguishes. And oftentimes we use like a stacked bar model because it’s like there’s something about these two quantities that makes them different. And often it’s an attribute. It’s,

you’re comparing this class to that class. So class one has this many cans, class two has this many cans. And I said that with conviction, but then I got home and I was like, that’s not always true. That’s partially true sometimes in some scenarios, but then when you’re, for example, looking at proportional relationships and you’re looking at change, you’re comparing change within a single attribute or a single unit.

Kyle Pearce: Right. Well, this is really interesting because, and now I’m not going to hold you to what you stated as being the exact words you used. Maybe they were, maybe they weren’t. But when you said it now, you did say often. So I do like that. And I do think when we leave the root, like I think when we use some of those examples, like always is a really, really scary one to use. You know, never.

is also a scary one to use. I like leaving it open. So I think you did leave it open. But I think maybe where the problem lies is that when we say often, in the court of law, it leaves it open to say pretty much like often could be interpreted in many different ways. But the problem is what does someone hear on the other end unless I’m more explicit about based on my current

learning, you know, like it’s almost like trying to incorporate that sentence before is that, you know, as I’ve been doing this learning what I’ve noticed so far, you know, like I like the so far idea as well, like a growth mindset idea is those two things. But I’d like to do some more thinking about it or something, right. But in the moment, you’re just like, my gosh, epiphany, we talked about math epiphanies all the time. And I think when you when you have one or think you had one

it’s really hard for us to not run out and like scream it from a rooftop because you’re like, look at what I noticed. Like this is pretty awesome. But then puts you and sets you up for, you know, I’m picturing that five hour train ride from Detroit to Chicago you just had and picturing you in the corner crying, thinking about this experience and you know how you’ve had a hard time getting over it.

Yvette Lehman: Well, and I think that the mistake I made is that I came in thinking I knew, and this was basically a whiteboard monologue from me. Where had I said to the room, because I was in a room with a lot of very knowledgeable educators, I could have said, I think that these two types of subtraction are experientially different. Let’s unpack that together.

Not only in that scenario would I not have walked away feeling like I misled them and I’ve left them with a false conjecture, but I also would have allowed the room to do the learning.

Jon Orr: So like you’re saying, like you’re saying like, because we come into some PD sessions, some sessions, some presentations, the work that you’re doing coaching, we come in with the confidence that naturally come along with the learning you’ve done. It’s possible the way that you phrase the information that you want to share.

shuts down any thinking in the room and almost like no fault of your own because you’re also kind of going well how if I rephrased it this way but also if I say anything does it does the fact that I’m standing in front of everyone else and I’m viewed as a position of authority does it automatically shut down the learning in the room because everyone just takes my word as truth.

Yvette Lehman: think that’s all part of it. And I think that also with my relationship with those educators, had I just stepped back and said, I think they’re experientially different. Let’s think of some scenarios. Let’s look at some models. Let’s model and arrive at some conjectures together. I would have also made those other educators feel more valued. But I unintentionally set almost a hierarchy in the room.

by being the knower and the person at the board and the one doing the talking about this topic. That wasn’t the entire meeting, but on the idea of subtraction structures, I was the one who knew, you know? And then I walked away thinking I actually wasn’t clear. I think I may have actually created a misconception or you know what we talk about, it’s like a…

when you lean into something and you lean into it too hard because you’re like, well, it’s always two attributes, but it’s like, that’s not true.

Kyle Pearce: Right, right. Well, I think too, it’s like the part that, first of all, I want to comment on, you know, your professional growth over the years and thinking about you are much more, in my opinion, aware, which I think is key, right? We have to know we have a problem, right? You’re more aware that these things are happening. I think back to

a lot of the portion of time that I was in these coaching or consulting roles and how unaware I was that that was probably happening left, right and center. And, and I was probably using more absolute language as well. So even though this one’s got you down, I would argue that you probably have some way better examples from like five or six years ago, right? When you’re like getting in this and they like ego is something you’re

constantly battling when you’re in a leadership mentor type position where you’re constantly having to battle this like imposter syndrome in your mind of like I need to show some sort of value here that I do know something like that’s a constant struggle that the vast majority of people have when they’re in that type of role. So to be able to recognize and to be able to notice and name it and then

to actually craft some steps to address it and maybe approach it a little bit differently, I think is a massive, massive strength that you have. Because like I said, for a very long time, I definitely did not have that.

Jon Orr: Right, now on the flip side, it’s like sometimes in my, you both know me, I will always try to think of the devil’s advocate, you know, position to many things. So, you where my mind goes to that is to say like, should then we always be like, how do you go into these situations specifically and have these thoughts be like, if I say anything without the disclaimer, then am I gonna,

feel bad about it or change my mind on it later. like, should I always be like, disclaimering when we enter these types of environments and relationships and sessions together? Or is that gonna hold me back from actually like giving my opinion? You know what I mean? So it’s like, do I just always say like, in my opinion, this is the way, but when you’re trying to coach or guide someone and get them to kind of think about it in a different way, you know, there’s like, somebody’s gonna be thinking that like, maybe I should just say nothing then.

Kyle Pearce:Yeah, that wouldn’t be a very interesting session that you know, or a very interesting conversation. I want I’ll speak to this, but I’m curious to see what event you’ve thought about as like, how you could do it maybe differently next time. Because, John, you’re bringing up a fairly we’ll call it extreme example, right? Where it’s like, hey, we’re not going to come into a room and no one says anything. But I think what makes it really

hard is like obviously and you vet you say this all the time the answer somewhere in the middle and and I would agree there think the hard part is trying to decide what information have I dedicated enough learning enough thinking enough intentional work around that I can say it with say more confidence than something that sort of maybe you noticed in the moment.

or that you only noticed that week or that you you’ve been thinking about but you haven’t really gone down the rabbit hole yet like I think the hard part is like how do you differentiate between those two because imagine if you vet if you did everything exactly the same way you did now you mentioned the fact that you know it was a lot of you talking I’m sure like we’d still want to try to get away from that it’s very hard for us you know and it’s very easy to get caught.

doing that when we’re excited to share something. But imagine, though, what you said and how you said it, and let’s pretend it was 100 % accurate. That could have done a really great service, right? And the problem, I guess, and what I see as the challenge is, how do I know in the moment as to whether that thing is something that I actually feel very confidently about and

is actually worth sharing and I do want people to walk away with and think about versus what happened here where you’re like, shoot, that actually wasn’t accurate or wasn’t complete is probably the right word.

Yvette Lehman: my lesson to myself right now or my self-reflection is actually something that you both do really well, which is to lead with curiosity. Now, this is something that I think you both do really well, which makes you strong coaches is that you are more inclined to ask a question than give an answer. Someone said to me the other day that his rule of thumb is to never answer a question you weren’t asked.

Kyle Pearce:I thought it was my hair. I shoot.

Yvette Lehman: And I feel like I answer questions I’m not asked all the time, where I need to be more mindful of leading with curiosity.

Jon Orr: Right. was going to say the, the, know, this conversation and, and, say some of those next steps often bring up the, the book that we’ve referenced about coaching many times here on the podcast, especially early in the podcast, when we were, were, you know, consistently sharing, you know, what we called mentoring moment episodes where we were interviewing, you know, teach practice in classroom teachers, or those, those coaching questions that we were asking folks. And we still continue to use those coaching questions in the work that we’re doing.

with our district partners and with teachers. that phrase from Michael Benye Steiner’s book, The Coaching Habit, those questions are really about holding back on advice giving and staying a little bit curious a little bit longer and continually asking those questions so that folks are really coming to conclusions on their own.

So I’ve been thinking about that book in this conversation, but then it’s also like up to a certain point before it’s like time to all of a sudden say something of value to help this person move forward or help this person kind of sidestep an issue or take new learning on that they didn’t have before. So there is that fine balance to stay curious, but then when there’s a time to say like, I think you need new learning here, is the time to step in with a little bit of authority.

Kyle Pearce:You know, that book and even the phrase, I think, is really helpful in this conversation, where it’s, again, stay curious a little bit longer. it’s almost like there’s a lot of words there. And I bet you the editor was probably sort of like, can we tighten this up? Can we make the? But it’s almost intentional, which comes back to what we’re discussing here, where it’s like, we’re not going to say you have to do it for a certain amount of time, or you have to.

ask three questions or you have to. There’s so much variability there and there’s so much, you know, uh, flexibility. And, uh, I love the idea and he does say it and he’s very intentional. He says, hold off on advice giving just a little bit longer. So it’s not like an either or it’s like a nice somewhere in the middle. It still leaves a lot of work for us as the end user of this thinking to go.

Where do I wanna line things up here? I think, Yvette, I’m picturing like you’ve got some pretty great next intentional next steps the next time you’re out there doing this work, right? Because you get excited, you’re in the moment. Like in the moment, you’re not thinking about how you’re saying it, but it’s like, but wait a second, if I can maybe just throw in a little bit more.

we’ll call it nuance around the current understanding. And you do use that language a lot, I must say. And I think that you’ve grown intentionally to do so. But for you to be able to hold yourself up in that moment to be able to say, based on my current understanding, inserting some of this language, kind of really, and the more often we use it, I think the more the person who’s listening or participating in the conversation

sort of starts to recognize that like, this is fluid, right? And I think the more we can make that explicit that, you know, two weeks ago, I did not know this, you know, and I know it now, but two weeks from now, I’ll probably know more about this thing. It’s like, how can we be more intentional about bringing that up? And I think that will help to, you know, reduce the number of scenarios where we walk away and go, man, I didn’t think about that one scenario that sort of made this entire statement, you know, inaccurate or less accurate, right?

Yvette Lehman: It’s sometimes a heavy weight, right? And I think that’s what I struggle with is that when I do feel like I have authority in a room and I do, you know, say something that I later have changed my thinking on, I almost feel this, like now I’m responsible for perpetuating a misconception or a partial understanding and I feel the weight of that. So I think that that’s a really good advice just to say, I think it’s tone too.

Right? Like just the tone you use and the delivery makes a difference. Like if you’re standing and you know how I am, like I’m a soapboxer. It’s one of my worst qualities as a presenter. I get so passionate, but sometimes when you do have those soapbox moments, it almost puts like an exclamation mark on it and it makes it feel really important. And then I get into these scenarios where a year later I hear, well, Yvette said,

Kyle Pearce:Yeah, it’s so incredibly difficult. And I think, you know, one of the, I think one of the big takeaways that I have as we come to the end of this episode, and I hope some, some listeners are feeling the same as that, you know, there is no easy answer typically when there’s a tough challenge out there, regardless education, math specifically, presenting, coaching, parenting, being a good friend to someone like all of these scenarios, the hard challenges.

There’s no simple answer, but yeah, there is no simple answer, John. I’m gonna wake up tomorrow and be like, I have the simple answer. Yes.

Jon Orr: Are you saying that with authority right now? Disclaimer, disclaimer, Kyle right now is saying there’s no simple answer. So go forth with that information, folks, I take that with the way you would take it.

Kyle Pearce: 100 % and it’s incredibly difficult, but I think for me that the key takeaway though is the noticing the naming it and then being intentional about trying to do something about it. I think is always going to put you in a better position the next time than you were the previous time, right? And I think it’s really easy for us to beat ourselves up when things don’t go exactly as we would like them to.

But if we can somehow have your network, like right here, hopefully that’s feeling a little bit better after today’s conversation, that it’s like you have your network, the people you care about, and then to be able to go, okay, yeah, that happened, but that doesn’t define what’s gonna happen next. And it’s like, how can I do it a little bit different next? And I think that is how we get better, regardless of it’s the content knowledge, the pedagogy in your classroom, the way you’re leading,

your team, it really doesn’t matter as long as you’re noticing, naming, and then actually trying to make actionable steps to do something a little different next time.

Jon Orr: think that’s a great note to end here today, I’m going to say folks again. Folks. Hey, go forth and make math moments with your fellow teachers and with your fellow students.

Thanks For Listening

- Book a Math Mentoring Moment

- Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

- Leave a note in the comment section below.

- Share this show on Twitter, or Facebook.

To help out the show:

- Leave an honest review on iTunes. Your ratings and reviews really help and we read each one.

- Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, and Spotify.

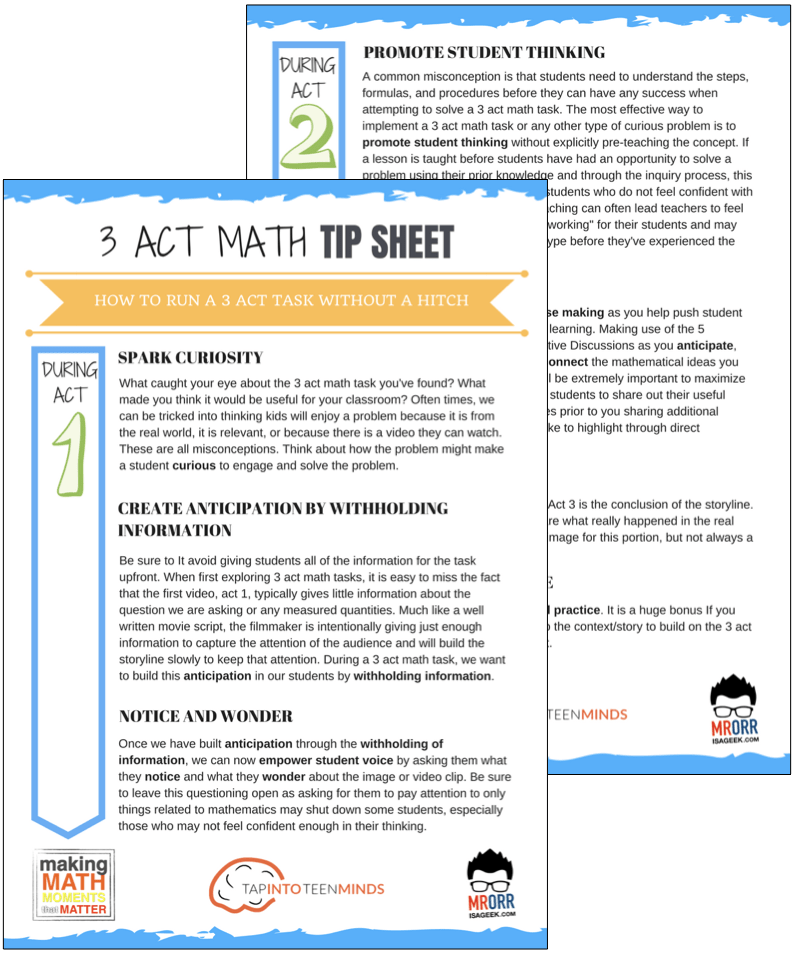

DOWNLOAD THE 3 ACT MATH TASK TIP SHEET SO THEY RUN WITHOUT A HITCH!

Download the 2-page printable 3 Act Math Tip Sheet to ensure that you have the best start to your journey using 3 Act math Tasks to spark curiosity and fuel sense making in your math classroom!

LESSONS TO MAKE MATH MOMENTS

Each lesson consists of:

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson consists of a Teacher Guide to lead you step-by-step through the planning process to ensure your lesson runs without a hitch!

Each Teacher Guide consists of:

- Intentionality of the lesson;

- A step-by-step walk through of each phase of the lesson;

- Visuals, animations, and videos unpacking big ideas, strategies, and models we intend to emerge during the lesson;

- Sample student approaches to assist in anticipating what your students might do;

- Resources and downloads including Keynote, Powerpoint, Media Files, and Teacher Guide printable PDF; and,

- Much more!

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson begins with a story, visual, video, or other method to Spark Curiosity through context.

Students will often Notice and Wonder before making an estimate to draw them in and invest in the problem.

After student voice has been heard and acknowledged, we will set students off on a Productive Struggle via a prompt related to the Spark context.

These prompts are given each lesson with the following conditions:

- No calculators are to be used; and,

- Students are to focus on how they can convince their math community that their solution is valid.

Students are left to engage in a productive struggle as the facilitator circulates to observe and engage in conversation as a means of assessing formatively.

The facilitator is instructed through the Teacher Guide on what specific strategies and models could be used to make connections and consolidate the learning from the lesson.

Often times, animations and walk through videos are provided in the Teacher Guide to assist with planning and delivering the consolidation.

A review image, video, or animation is provided as a conclusion to the task from the lesson.

While this might feel like a natural ending to the context students have been exploring, it is just the beginning as we look to leverage this context via extensions and additional lessons to dig deeper.

At the end of each lesson, consolidation prompts and/or extensions are crafted for students to purposefully practice and demonstrate their current understanding.

Facilitators are encouraged to collect these consolidation prompts as a means to engage in the assessment process and inform next moves for instruction.

In multi-day units of study, Math Talks are crafted to help build on the thinking from the previous day and build towards the next step in the developmental progression of the concept(s) we are exploring.

Each Math Talk is constructed as a string of related problems that build with intentionality to emerge specific big ideas, strategies, and mathematical models.

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Use our OPEN ACCESS multi-day problem based units!

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Partitive Division Resulting in a Fraction

Equivalence and Algebraic Substitution

Represent Categorical Data & Explore Mean

Downloadable resources including blackline masters, handouts, printable Tips Sheets, slide shows, and media files do require a Make Math Moments Academy Membership.

ONLINE WORKSHOP REGISTRATION

Pedagogically aligned for teachers of K through Grade 12 with content specific examples from Grades 3 through Grade 10.

In our self-paced, 12-week Online Workshop, you'll learn how to craft new and transform your current lessons to Spark Curiosity, Fuel Sense Making, and Ignite Your Teacher Moves to promote resilient problem solvers.

0 Comments