Episode #434: When Early Strategies Are No Longer Working: Helping Students & Teachers Move Toward Efficiency in Math

LISTEN NOW HERE…

WATCH NOW…

Ever watched a student solve 146 ÷ 12 by drawing 146 dots… one by one?

In this episode, the MMM team dives into a common but frustrating classroom challenge: students who cling to inefficient math strategies like counting on fingers, skip counting, or repeated subtraction—long after they’ve outgrown them. These early strategies worked, and students trust them. So how do we help them build confidence in more sophisticated approaches?

You’ll hear from our newest team member, Beth Curran, as we unpack why students get stuck, what teachers can do in the moment, and how school leaders can build the conditions for long-term change.

Listeners Will:

- Understand why students cling to familiar but inefficient math strategies

- Learn what teachers can do in the moment to nudge students toward more flexible thinking

- Explore how dynamic assessment and anticipating student responses builds instructional skill

- Hear how one district used the Five Practices to build teacher capacity over time

- Reflect on what it takes to build a math improvement flywheel that actually gains momentum

If you’re supporting students—or teachers—who are stuck using early math strategies, this episode gives you real steps to move forward with clarity, confidence, and purpose.

Attention District Math Leaders:

Not sure what matters most when designing math improvement plans? Take this assessment and get a free customized report: https://makemathmoments.com/grow/

Ready to design your math improvement plan with guidance, support and using structure? Learn how to follow our 4 stage process. https://growyourmathprogram.com

Looking to supplement your curriculum with problem based lessons and units? Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons & Units

Be Our Next Podcast Guest!

Join as an Interview Guest or on a Mentoring Moment Call

Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

Book a Mentoring Moment Coaching Call

Are You an Official Math Moment Maker?

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Jon Orr:

All right, we’re gonna get into it here today. We’re talk about how students are relying on inefficient strategies and what we could be doing sometimes specifically when we’re helping kids with strategies at varying levels and help them progress to say a more clever, we’ve used that word before, like more clever, a more sophisticated strategy and we all want that. So we’re gonna get into that, but before we do, we want to welcome a guest. We have a panel of four here today. We have Kyle’s here, Yvette’s here, but Beth, Kieran is here, she is a new addition to the Make Math Moments team. We are proud to have her as a joining member here. We’ve invited her to participate today in our discussion on this, and I think it’s a very appropriate, ⁓ timely discussion, and I think Beth can share a lot of insights. So Beth, welcome.

Beth Curran:

Thank you, John. Happy to be here.

Jon Orr:

Awesome, awesome. Now, hey, we’ve gotta do a little bit, we gotta do a little thing here, Kyle. Like we’ve asked, like every guest we’ve ever had, now, I don’t want you to think that, you know, Beth, I don’t want you to think of yourself as a guest. I want you to think that this is your home. But ⁓ we ask every guest what their math moment is. So when you say like math class, there’s always like this image, this kind of like lingering thing that sticks with you through all these years. So if I said math class, what’s the math moment that stuck with you all these years, Beth?

Beth Curran:

So I’m going to give you a little bit of history about me and math. I always felt like I was a good math student. It was never something I had to worry about. I was not very good at picking up on reading. So math was kind of like my thing when I was a young child. And then all through middle school, high school, I had the ability to listen to what the teacher said, follow that example that the teacher had given me, and basically plug and chug and do well on my assignments and on my assessments.

Kyle Pearce:

Plug-in chug. Love it.

Beth Curran:

I never really enjoyed math class though, but it was something that I didn’t really have to worry about. So I guess in a way math was kind of comforting to me because I didn’t have to worry about. I could put in very minimal effort and get good grades because I was a good memorizer, which is something that came to me much later. I didn’t realize that that was why I was doing so well at the time.

Beth Curran:

I didn’t enjoy math though, even though all the aptitude tests said go into this math field. I entered college in engineering and absolutely hated it. So kind of shifted, moved into other areas that were more interesting to me. And then ultimately I landed in a teaching position. So I think looking back on it, I probably should have pursued that somewhat sooner in college. But my math moment was really when I was teaching fourth grade.

I was probably in my late 30s, early 40s at the time. I had a fourth grade student come up to me and say, Ms. Curran, I never really understood how come when you subtract across zeros, now he didn’t say that, but it was like 200,000 minus some crazy number. He said, how come when you subtract across those zeros, some of the zeros turn into nine and some turn into 10? He said, I never understood that.

Beth Curran:

And I kid you not, I was instantly like flashback to second grade to third grade when I was being introduced to this standard algorithm. I confused that as well. I would cross off the zeros in the middle and make them 10 and make the last one a nine because it was just a procedure. didn’t make sense to me. And I looked at him and I knew there was a good answer, but I did not have

Jon Orr:

There’s gotta be, right?

Beth Curran:

the resources, the curricular resources to provide him an answer that he wanted. So I said to him, you know what? I want you to just hold onto that thought. I’m going to go home tonight and I’m going to play around with this. I know it has something to do with place value and I’m going to come back tomorrow and explain it to you. And so I did, I did that all on my own. And I think that was my moment when I realized the way that we’re teaching young learners needs to change because they’re curious. They want to know why.

Beth Curran:

things work. And I can remember myself being in a situation in the classroom and asking my teacher, why does that work? Oh, don’t worry about it. Just memorize it. Right. So I think that was my big math moment. I mean, was admittedly late thirties, early forties, and I could not explain to that student why that worked in a fourth grade classroom. I had to go back and I had to dig into it myself. So, you know, that was kind of the moment where I realized that we need to be presenting math in a different way.

to young learners because we have calculators, we have computers. Calculation can’t be the end all anymore. They really do need to understand concepts and see connections between concepts and apply all of that to problem solving.

Kyle Pearce:

Well, thank goodness that you were the type of individual who didn’t want to just leave that question unanswered because I think there’s many, many of us, and I’m sure we’ve all experienced it where you just sort of like shake it off and move along and don’t really reflect on it. So clearly you were reflected on it. It’s an important question. And probably more important is the fact that I’m teaching this concept.

And I actually don’t necessarily understand the concept as deeply as I probably should. Right. And I think that sort of summarizes the work that we’re trying to do in mathematics education in general. And I think it’s a good lead in to what we’re going to be chatting about here on the episode. So Yvette, us up on our conversation we’re going to have today with a I’m going to call it a common educator challenge that we see around there and what we might be able to do to dig in.

Yvette Lehman:

I think based on Beth’s math moment, you can see why we invited her to this conversation today. That’s such a natural fit for our team in deeply understanding conceptual math. And so we’re gonna unpack a problem that many teachers can probably relate to. I remember experiencing this in my own junior classroom. Imagine you have a fourth, fifth grade student who’s now performing operations with larger quantities. So we’re multiplying, we’re dividing, we’re adding, subtracting.

but those students are still relying on the strategies that they developed K2. So they’re still relying on counting with their fingers. They’re still relying on, you know, it’s a division problem and they’re going to draw out all of the items and then circle groups of 12 and then count the groups or, you know, they’re still relying on repeated addition or repeated subtraction or skip counting. But now those strategies that once served them are becoming really inefficient.

and they’re leading to a lot of errors because the quantities are just too large to be able to accurately leverage those kind of early counting, early addition strategies that students developed. And so the question that we’re going to tackle today is if I’m a teacher and I’m seeing this behavior in some of my students or I’m a coach and I’m supporting a teacher who’s saying we’re getting stuck because students are still relying on these inefficient strategies, what’s the move?

Yeah, well give me give us an example so everyone in listening can paint this picture like like what is like when you’re saying strategies and inefficient versus efficient or clever like like tell us Let’s use an example here just to paint the picture

Yvette Lehman:

Yeah, so the division one, I think, is a good one. Have you ever seen this in a junior classroom where, you know, you’re getting up to large quantities and it’s like, you know, 146 divided by 12 and the student is relying on drawing 146 circles on their page and then circling the groups of 12, counting them and they’re counting the 12 one-to-one because they don’t have a system to organize the 146. They’re counting them one-to-one and then they’re circling. It’s a lot of one-to-one counting that they’re relying on.

Jon Orr:

Hmm, I see. Right?

Yvette Lehman:

And again, you know, to draw all of the 146 circles to make sure you and then that I’ve seen this so many times they go to draw the 146, but then they lose count or they they miscount and they have to count them again. And so think about how long that’s taking and how inefficient it is. But it seems like, you know, this is what the student has to rely on. They’re relying on counting because they trust counting.

Yvette Lehman:

And they haven’t moved beyond that to a more sophisticated strategy to tackle this division problem.

Jon Orr:

I see. So it’s like, I think the key line there you just said is they trust that they’re like, they’re like, I know this works and I know and I understand it. And then I feel confident using this strategy. And if I felt confident using another strategy, then I probably would use that. But I just don’t because I don’t have one and I don’t think about it because there’s not one that I can, that’s internalized to me as a, as a very reliable strategy, so therefore we all default to the level of our most accessible strategy instead of the ones that we could be using because we just don’t understand them.

Kyle Pearce:

Well, and I think when we talk about efficiency and mathematics, like we’re always thinking it’s easier to be more efficient, but it’s actually a lot harder because you have to do a lot more thinking if you’re not confident in that strategy, right? So by counting, you know, one to one, even though it takes a lot longer.

it’s certainly easier from a cognitive understanding and cognitive load perspective, right? So, let’s dig in here and let’s chat a little bit more about what do we do when we find that students are, we’ll call it stuck with a less efficient strategy than where we’d like to see them along the journey.

Yvette Lehman:

hearing once and I can’t remember I wish I could quote the researcher but they said essentially think about how many exposures students have had to that counting strategy by the time they hit fourth fifth sixth grade is probably thousands thousands of times that they’ve relied on that strategy and it has worked for them can we say the same for the other strategies that we’re trying to help them have ownership of

Yvette Lehman:

Like when I think about, you if I want students to have ownership of another strategy, I want them to be able to use partial products using their understanding of twos, fives and tens. I think about the number of opportunities they have to have had to own that confidently so that it’s in their back pocket and they know that they can trust it and they can use it reliably and it’s going to get them an accurate answer. And so I want to be cautious in saying,

I don’t think we need to sit down and do hundreds of these at a time. But if we’re trying to build up their toolkit of strategies that are in their back pocket that they can rely on, that they trust, I think we need repeated exposure and multiple opportunities to experience them. And to me, it’s like in short bursts every day, 60 minutes of it in a single day and then not revisiting it, but every day short bursts.

Yvette Lehman:

of opportunities for them to really develop and own these more efficient strategies so that they can trust them and they can pull them out of their back pocket.

Beth Curran:

Yeah, so I’m gonna kind of build on what Yvette said here. I mean, I 100 % agree with the fact, well, everything, everything that Kyle said and Yvette said that students are comfortable using these inefficient strategies because they’ve had the opportunities to practice them over and over and over again and never really being pushed to maybe thinking about numbers and calculations in different ways. And to kind of to build on what Yvette was saying about finding those opportunities for practice. It doesn’t mean that we have to spend a half hour drilling students on how to use these alternative strategies, if you will. But what it means is that when given the opportunity, because math, in math class, we’re solving lots of problems, right? So when given the opportunity to solve some sort of calculation, we need to equip teachers.

Beth Curran:

with the understanding of these flexible strategies themselves so that they are encouraging students to approach problems with more flexibility in the moment, not creating separate lessons that just focus on these strategies. But in the moment, can a teacher say, okay, this student counted on their fingers or made groups of 12 or something to divide, did anyone do it a different way? And just

Beth Curran:

pausing and having that opportunity to practice that flexibility and thinking in class is going to provide students with that exposure. Also, if calculation is you’ve discovered that it’s a pebble in your shoe, students are not using efficient strategies and that’s something you want to work on, then you definitely have to encourage students to step out of their comfort zone.

Hey, student, you solved it by creating groups of 12. We just talked about this other strategy too. Could you try that as well? So I think that if we can shift math class, especially in the lower grades, away from quick answer getting to more focusing on developing numbers and flexible strategies, then teachers will realize I don’t have to get through a bunch of problems to see if they can answer correctly. It’s more like.

Beth Curran:

What was the focus of the lesson here? Look at all the flexibility, number sense that they were able to develop. so, you know, so that’s, I just mentioned a whole lot of really big things there, but.

Jon Orr:

Yeah, exactly. Yeah, for sure, for sure. It’s like, what you’re saying is that paradigm shift of like, what are we really striving for here in the class, like this lesson? It’s like, what’s the big idea? And we have to accept that if we want our students to be fluent in round number sense, we have to dedicate time and make that the focus is to say, like, because I think what’s happening, right, is that too many times we’re flipping to the calculator, we’re flipping to like,

Jon Orr:

go right to the algorithm because we think it’s the most efficient strategy because if I help them with that, then they can always fall back to that instead of spending time on say, these strategies that could be useful for mental, you know, people will say like, you wanna do it in your head or mental math strategies. It’s like, well, if we want kids to have those strategies, we need to spend time on them. Therefore, the purpose of the work has to be about doing more of that.

and being okay that it’s gonna take some time and making sure that when we are modeling for students, we are explicitly talking about the strategy or the model that helps this strategy kind of emerge. So I think that’s that paradigm shift that we need to make for ourselves. But like Beth, you touched on, I think the gatekeeper here is that we ourselves rush to those when we’re doing calculations as educators. So if I’m a coach or a coordinator and I’m helping educators, and I want those more strategies,

Jon Orr:

Have we taken the exact same approach when helping and working with our educators? Like, are we spending time with them to help them see those strategies in the same way we want the teachers to spend time with kids on those strategies? We have to dedicate that as well because our teachers don’t know it. Typically, typically, like you went down the rabbit hole because you’re like, I need to know this. Some teachers have that. you’re listening to this podcast, it’s likely that was you, you know? But.

Jon Orr:

you’re working with or supporting or you have colleagues who just haven’t gone down that road, the rabbit hole yet. And it’s like we need to have those math epiphanies on a regular occurrence so that they can then go, my gosh, the big idea here is to put the calculator away, is to push the algorithm to the side for a little bit to develop these types of strategies so that kids have something to fall back on when the numbers get bigger, right? When the strategies, when the things get tougher, it’s like we don’t wanna have to go back to the most efficient or the most inefficient strategy because it’s the one that they feel confident on.

Beth Curran:

Yeah, if I could, no, go ahead. I was just going to say if I could wave my magic wand in classrooms around calculations, I would have teachers no longer write equations in standard algorithm formats on the board. I would have them always write them horizontally. I think that one shift can bring so much more number sense and talk around the numbers into the classroom. But,

Yvette Lehman:

You just made me think of me. sorry, go ahead Beth.

Beth Curran:

we’ve all seen the example where a teacher puts 18 minus nine on the board and then crosses off the one in 18, makes it a zero, then crosses off the eight, makes it 18 again. we’re thinking that calculation is standard algorithms as opposed to all the flexibility and number sense that can be built. So my magic wand would be stop writing equations on the board in standard algorithm formats. start writing them horizontally.

Yvette Lehman:

So this is making me think about from the coach perspective. know, imagine now you are supporting a teacher who wants to engage in what Beth is describing, which I am interpreting as dynamic assessment. That’s how Cathy Fosno describes it in conferring with young mathematicians, the ability to see where a student is, what strategy they’re using to solve and advance them. And it makes me think of the work that one of our districts did. So we have a district in Louisiana who did a lot of work last year around five practices, but

All they focused on was anticipating and looking at assessing and advancing questions. And how, why I think this really connects to what Beth was describing as far as the next step is that I need to be able to think about if my student solves this division task by drawing all of the circles and trying to circle the groups of 12, then what? What is my advancing question to that student to help nudge them along the developmental continuum?

So think about that particular practice within five practices, where you look at the task, you anticipate all of the ways that students might approach it. Just that alone is capacity building for educators. Because when we do that together, we see that there are more ways than just accessing it through counting or accessing it through the standard algorithm. There are all of these other strategies that exist. But when we engage in that practice together and that, and again, the five practices is a lot to unpack.

So that’s why this district said, we’re just going to focus on, here’s the task that we’re using. We’re going to anticipate how students might go about solving and we’re going to plan for how do I take the student who drew all the dots today and help move them towards thinking about maybe a fact that they’re familiar with, like, well, could, would you be bold enough to say, I know for sure there are 10 groups of 12 because this number is greater than 120.

And how do but we have to, as educators know that developmental continuum in order to push students along, which is why doing this work collaboratively with a network of other educators like our district in Louisiana has been doing is such a valuable exercise.

Kyle Pearce:

And you know, like something I always like to take these ideas and I try to put them in other contexts in life. And, you know, and, and when we’re talking about say building up skills in any say sport, you know, and I’ll bring up the hockey example, Canadian example here, but you know, we can teach our kids and our players to skate as fast as they can. We could teach them how to shoot, but if we don’t

work on other skills and other opportunities for them to, you know, pivot and do different things on the ice. They’re not going to be able to play the game to, you know, their their best, you know, potential. And the same is true here with mathematics as we’re working through the problems. And Beth, you said this earlier is like really reshifting why we’re doing what we’re doing and really making sure students understand that we are not

as interested. And I don’t want to demote the idea. I don’t want to go down the rabbit hole of the answer doesn’t matter. And, you know, accuracy doesn’t matter. That’s not what we’re talking about here. But we’re talking about the point of the work we’re doing today is to help you build your skill set and to help you build your strategies. And of course, over time, build your trust that you can actually use that strategy to solve problems when you may not have a ton of time.

Kyle Pearce:

to think it through. And I think that’s one of the big like chasms that we have is like when we go to the inefficient strategy, we just know it’s going to work every single time without thinking about it. And I can just get to it. Whereas if I’m working with a strategy that maybe I saw, you know, once or twice in math class, or we tried once or twice here or there, basically, I’m going to always doubt that I have a full understanding of it that I have a trust

that I can lean on that strategy in all sorts of different situations and contexts. And that’s going to essentially box me out from going down that path. And I’m just going to go, you know, I don’t have the time to think this through. I’m going to move back to this inefficient strategy. So I think these are things as we’re developing our lessons. And, you know, when we think about as the numbers get larger, you know, we, have to be really strategic about moving up that progression.

you know, or moving down that progression intentionally so that students have the opportunity to kind of take what they know, still have a little bit of trust there, but then play with some of the unknown, you know, and like play in this land to understand the behaviors, to understand what’s going on so that they can actually bridge that gap and start to build more and more trust. Now they can move a little further down that road and feel more confident doing so. So

Kyle Pearce:

when we’re structuring this and as coaches who are listening to this podcast, when we’re working with our educators, like we really have to be cautious about not pushing too fast to get down that road because I know we have time and I, or I know we have time. I know we have time limitations and I know we have many standards that we’re worried about, concerned about. And ultimately at the end of the day, we have to just be very, very cautious not to sort of rush down the road. Otherwise

Kyle Pearce:

the time that we are taking to introduce strategies is probably wasted time, right? Like if we’re not taking enough time to do it well, then we’re actually wasting the time. We may see, you know, less favorable results than had we just chugged in plugged, I think is what Beth said. I love that, that expression, you know, so rushing to that algorithm, you know, the result might turn out better if we’re going to half bake.

Kyle Pearce:

the strategies approach. So we have to be really cautious and aware of that.

Beth Curran:

Right. Excuse me. And I want to just build on a couple of things you said there, Kyle, because you kind of breezed through it quickly. And I think it deserves a little bit more emphasis. The idea that, again, getting back to our comfortable strategy, whatever that might be, counting on our fingers, using a standard algorithm, whatever it might be, and encouraging students to step outside of that and practice. So the more that students are provided opportunities to

use their comfortable strategy to get that answer, but now try a new strategy. The more opportunities they have to see that trying my new strategy, I get the same answer as the old strategy. So then they start to develop this trust. And so it’s all about getting students to a point where they trust that this other way of thinking about and looking at numbers and thinking about calculating.

Beth Curran:

because they’ve had the opportunities to like maybe check with their old favorite strategy. And so they’re seeing that they’re ⁓ using these new flexible strategies, they’re also able to get the correct answers. And I find that often working with adult learners as well, working with teachers who in trying to expand their understanding of flexible strategies is, I’m not gonna say don’t count on your fingers or don’t use your standard algorithm.

No, that’s your comfort zone. Do that. But now try a new strategy as well and see if you get the same answer. And the more that they’re provided those opportunities to do both, right? And see that they’re getting the same answer, then they start trusting in these other ways of calculating.

Jon Orr:

Yeah, well said. Well said. So we think about zoom out for a sec. Like the thing about the big picture here is like we’re helping our students be, you know, have strategies, rely on those strategies, be confident with those strategies. It takes that that focused effort. know, Beth, like you were like, I needed to realize that I needed to go down a rabbit hole, you know, teachers, teachers do that, like we go down rabbit holes. If you if you zoom out a little bit, what’s happening is like

Teachers are building their capacity in the area of mathematics to make that possible, to make that the focus of the work that you’re doing. If you zoom out a little bit more and we’re supporting teachers, we have to dedicate time to helping those educators because you can’t just assume that everyone’s gonna go down the rabbit hole on their own. You need to create those epiphanies for them to all of a sudden start to go down that rabbit hole. Therefore, we have to dedicate that time at our, school level or in our PLCs or at the district level when we have full day pullout sessions like,

We have to think about that in the work that we do in the Louisiana district is they made that commitment to capacity building, which is part of your math improvement flywheel is that we have to spend time there because we can’t solve these problems like students moving from one strategy to the other without building that as part of your math improvement planning. Zoom out a little bit more because it’s like, how do you make that happen? You have to think about the structures that you have inside of your school or your school district.

You have to optimize those structures to make sure that we’re making use of that. And how do you do all of that? Well, you have to zoom out a little bit more and say, like, we have to have the one thing. Like the Louisiana team was like, we’re going to do one thing. And we’re going to do one thing really well. And that gives us the focus to structure our support so that we can build capacity with educators. Because in previous years, they were throwing spaghetti at the wall and just hoping some of these things stick without real purpose, real structure, real focus.

So when you put all those pieces together, you have that flywheel that starts to turn and it’s, and even think about it, was thinking about this the other day when you have a flywheel, it’s like, sometimes it’s like people think it’s like, you have to just get that flywheel by doing this one big push. And all of a sudden it moves, you know, like it’s like, ⁓ we, we’re going to have our summer PD kickoff session and that’s going to be the get the flywheel moving. But a flywheel doesn’t move by one big push every summer. It moves with little pushes all year long on the things that matter.

Jon Orr:

and that’s what this Louisiana team was doing well, and that’s what we wanna do. If we wanna build capacity, we gotta figure out what are those little pushes all year long on that capacity building so that teachers have what they need to address these strategy problems so that students can do this type of work. So we gotta build that math improvement flywheel. We know you’re listening. You wanna build that math improvement flywheel too, no matter whether you’re at school or whether you’re in the classroom or whether you’re at the district coordination level. You could always learn about the math improvement flywheel a little bit more.

head on over to makemathmoments.com forward slash grow, makemathmoments.com forward slash grow, take that assessment there and start learning about your flywheel now.

Yvette Lehman: How many times have you heard teachers share their frustration that, you know, my students just are struggling with computation? It’s like, just the four operators, we’re adding, subtracting, multiplying, dividing, and, you know, the algorithm isn’t working for them. A lot of inaccuracies. Students are coming up with answers that are not even reasonable, and then they’re asking themselves, you know, and we look at the solution and we’re like, does this even make sense?

Jon Orr: Yeah.

Yeah.

Yvette Lehman: and the students like, have no idea if it makes sense because I just followed the steps.

Jon Orr: Sure. That’s a main problem. think that here’s the next problem though, right? We want then to say, let’s not focus on the algorithm, let’s focus on strategies and maybe making use of models. But I’ve tried that. I’ve tried the multiple approach, but that’s even… That might be even more confusing and therefore I should just stick to one thing. Like let’s just give one solution. Like you recognize this is the problem, do it this way. Because at least then I’ve given them the one way to solve that. then, cause I feel like giving them too many options is confusing students.

Yvette Lehman: I actually just heard this last week from a teacher. That was exactly their reaction, right? It’s like, well, if the algorithm isn’t working for you and it’s not working for your students and your students are coming up with answers that are unreasonable, maybe there’s another way to approach that computation. And you’re right. The first reaction was like, I’ve tried that. And it just gets messy and it’s confusing. And if they can’t master one approach, how am I going to get them to own more than one?

Jon Orr: Mm-hmm.

Great.

Yvette Lehman: So now imagine you are the instructional leader in this building. And so, you you’ve identified and the staff agrees, know, your teachers are saying, yes, we want our students to have increased computational fluency. We want them to be accurate when they’re working with all four operators. We recognize that maybe for some, the standard algorithm approach is not working, but we’re also reluctant to teach more.

Jon Orr: Yeah, we’re not convinced.

Yvette Lehman: strategies. They’re not convinced.

Jon Orr: Yeah, we’re not convinced that the more is the more is better approach, you know, the optionality isn’t isn’t the better approach. It’s more it’s louder, stronger, you know, and more repetition of the first approach. That might be the ticket because it worked for me, you know, it worked for us, you know, but that’s that’s easier than trying to do, you know, all the other stuff because it’ll just confuse them more.

Yvette Lehman: We’re working with a principal right now. And what was really, I think, amazing about this particular site is this, identifying the problem that they wanted to solve was actually pretty easy for the staff. They came to a pretty quick consensus that, of course, they would all like to see their students increase their mathematical fluency as defined by working flexibly with all four operators based on what’s appropriate for their grade level. Where they’re struggling, is on the solution, agreeing or committing to a strategies-based approach. And so this principal is now in the position where I don’t think she is confident to move forward with the solution until the teachers themselves have some mathematical epiphanies around the value of maybe having more than one way to solve a problem.

Jon Orr: Mm-hmm.

Right.

And that’s, and that’s typically the, you’re saying is, is, typically the, I, the recommended solution that we talk about our teams with is, is when we are seeing resist, you know, I tried that multiple approach or multiple strategies approach, or I think the one way is the best way. How do I get my, how do I help my teachers see that being flexible is, is, is a better skill or a more worthwhile skill? to have as a student, but also as a teacher, then trying to just memorize the one way. Because that’s typically what these barriers are, is that we know that this is better for our kids in long run, but it’s hard to kind of get over the hump, I guess. What does that look like? How do I support? And the supporting, our recommendation is, this is what you’re helping this team with, is to say how many… But we have to help everyone with more access to like have those math epiphanies. Like what are some of those, the strategies that they don’t have? Because if I’m saying I think that one way is the better way, it’s just likely that I just haven’t had the confidence around all the other strategies to create the flexible superpower that I could have. And if I spent time supporting educators to create that,

Yvette Lehman: Mm-hmm.

Mm-hmm.

Jon Orr: and embedded into any sort of collaborative time we have together, then down the road, they’ll have like, it’ll be like through no fault of their own, all of a sudden they’ll have these strategies to rely on. And that is the convincer, right? Like the convincer isn’t like, just do more of it. The convincer is like, you’ve got to build their capacity up.

Yvette Lehman: The advantage that this particular site has is that they are willing and able to commit time every week to this work. So they meet as a staff weekly and a portion of that staff meeting every week is reserved for math because math is a priority at their site. Yeah, it’s awesome. They come together as a full staff. This is a K-5 school. And so where we started with this team is we had to start to shift belief. and shake up a little bit of the resistance. And so we started by engaging in some webinars together, watching some videos, and we used an ICQ protocol, which is that confirms my current belief and something that I’m questioning. So it leaves space for people to say, I don’t believe this, know, or this, I’m not convinced of this. So we’ve created two opportunities so far. The first one was we had them engage with Jennifer Bay Williams session from the summit, you know, where she basically talks about, I wanna say in the first 10 minutes, it’s like, She pretty bluntly says, you know, the ways that sometimes we try to say students are going to build their fluency, you know, through rote practice and memorization is just, the research does not back that. And I think sometimes people need to hear that from somebody other than their instructional leader in their building. You know, somebody that’s respected in the math community and again, with space for them to also push back or challenge. Like this was not a space where it’s like, let’s watch this webinar and everyone needs to agree.

Jon Orr: That’s right.

Yvette Lehman: It’s just an opportunity to begin having some discourse and to maybe start questioning if the way that we were taught or the way that we’re teaching is actually getting us the results we want for students and maybe opening our eyes to the possibility of there being another way that we hadn’t yet considered. I also really love there’s a YouTube clip from Christina Tondevold and we’ll link it in the show notes. The clip itself is actually about the difference between procedural fluency and conceptual understanding. But in this 10 minute clip, she talks about some really great examples of where the standard algorithm fails us, where it’s just super ineffective. And so she does, of course, know, the 1000 minus 999 stacked standard algorithm. And it’s like, wow, if I use the standard algorithm to solve that problem and I can’t just see that it’s one, like.

Jon Orr: Mm-mm.

It’s a lot of carrying. Yeah.

Yvette Lehman: That is such an inefficient way to approach that problem and really shows a deep lack of understanding of the behavior of subtraction. The other example she gives in the video is she talks about going into high school classes and students have to subtract 17 minus nine. And so they write it 17 minus nine stacked, and then they borrow the one and they still have 17 minus nine. It’s like we’re no closer to an answer.

Jon Orr: I’ve seen that, yeah.

Yvette Lehman: Right, of course, because we’re blindly following, right, we’re blind,

Jon Orr: I’m borrow the one again. You just didn’t do it enough.

Yvette Lehman: right, we’re blindly following these procedures that really aren’t helping us get to an answer. And so that’s where we kind of started was we just needed to shake belief a little bit and create a space for dialogue where we have a conversation starter about maybe the standard algorithm isn’t always the best way to approach problems. And wouldn’t it be amazing if students didn’t get stuck in these traps of being very inefficient or coming up with very inaccurate answers because they don’t know what they’re doing.

Jon Orr: ⁓ Yeah, yeah. What I love about what this team has done, you know, because if we think about the high level in terms of math improvement planning, because that’s really what’s happening here, right? Is that we’ve recognized that there needs to be a shift towards making sure that there’s fluency strategies happening in our classrooms and multiple strategies that are priority for where we’re trying to go. Therefore, I need to make that shift in our classrooms or we need it as a collective group need to make that shift in our classrooms. And instead of just saying, is where we’re going, here’s what the, we’re going to choose a curriculum and we’re going to stick, know, that follows this and do this and follow this with the pacing guide and go down this route. It’s, it’s they unpacking and taking into a consideration some really big elements of what you need to include for math improvement planning, which is one is realize that the barrier to most shifts is the content knowledge for our educators in the unfamiliarity of multiple strategies, multiple models, and what, say, models stretch vertically, which ones we need to rely on more than others, which strategies we could be helping with, like our students with, coming at it from the conceptual towards the procedural, like just having that fundamental belief shift happen, but also supporting that shift. in terms of the educators own capacity building around their own mathematical thinking and their own mathematical proficiency. We just don’t have that, you know, we don’t have that familiarity that we need our educators to have. And it’s not their fault. It’s it’s it’s we came through a system that just didn’t, you know, teach math and we still consistently don’t teach math that way. And we need to teach it to our educators or give them experiences. So I love that they’re focused on. But the other thing I really love is as another big picture element, like we got four big problems we solve with our teams. And one of them is obviously building capacity and making sure we’re focusing on that. The second one that they are doing a really great job on is making use of their subsystems for instructional improvement. they’re, you’re saying they’re, the priority here is to create epiphanies for mathematics so that it will translate into instructional practices down the road or even now. But we gotta make use, because we recognize a priority, we gotta find the time. Because it’s like, we don’t have time to do that. But it’s like, find the time. The fact that they’re meeting every week to do this type of work, it means I put the priority here. I’ve decided this is the priority. we’re going to come together to do more math together as a prior. And we’re going to make use of that collaborative time in that way. We’re not going to treat this like, you know, all the, all the logistics that we could be going over in this, all the stuff that could have been an email. We’re actually going to use this time to do this type of work because it, it’s going to lead us down this pathway. And there’s, can see what the future will look like if we stick to these two, really two things, focus on math. make use of the collaborative time to do it.

Yvette Lehman: I remember when I first met with this leader, that was one of her hesitations, I guess, is that she didn’t feel she had support or subsystems. So she’s a single administrator, no coach, no lead teacher, no math con, it’s a single administrator building, and they don’t have any embedded teacher collaboration time or PLCs. And so I think when this journey began, she actually was…

Jon Orr: Right?

Yvette Lehman: concerned about not having the right supports in place or having the subsystems, but the fact that, like you mentioned, she’s committed that, okay, the one system we do have is staff meetings. We have a staff meeting every Wednesday. She’s committed that, like you said, any of the logistical things that would be monopolizing that time are being put to the side, sent in email, addressed very quickly so that they can carve out, and sometimes they actually dedicate the whole hour. to math, you know, it’s a minimum half of the time, but most times it’s actually the full hour that they commit to this learning because it is a priority and their data, their benchmark assessment, their standard state test assessment suggests that there’s a critical need in math. And so this is how they are dedicating their professional development time this year. I also understand too that at the elementary level, math is often not the only priority, right? So it’s challenging, like it certainly is, but I think that they’ve done a really good job of saying, We know we can’t tackle everything at once. We don’t have the capacity. We don’t have the systems. So this is the one we’re going to commit to right now. And we’re going to go all in and we’re going to use all the time that we possibly can. I’m excited for this team’s journey. So I’m picturing, you know, I work with this principle and we come together after every staff meeting. We reflect on what emerged and then we plan. So we always gather some type of exit ticket or she does some anecdotal documentation to get a really good sense of where the room is at. so that we can target the learning for the next session. And so what I obviously would like to get to with this team is that they are doing math, right? So right now we’ve been mostly understanding the why or creating a space for dialogue, but now we need to get into a routine of every time we come together, we are building our own toolkit of strategies that we are better positioned to solve problems that don’t lend themselves to the standard algorithm with efficiency. The advantage this team has though, the principal does have a math background. So I just want to put that out there for everybody, right? That’s also a huge factor when it comes to this work at the school level.

Jon Orr: Yeah. Right. Right. There’s two conditions. She has the two conditions that you really need at a school level to do this type of work consistently. If you’re going to make use of those subsystems for and support, like a staff meeting or PLC is that you’ve got a skill facilitator who can lead individuals and can facilitate sessions and can rally the troops here. But then you also have a math. an understanding of the progressions of mathematics. Like you have a solid understanding of like what is important in mathematics. Like you can decide, like you can have that what’s important in mathematics, like fundamental core beliefs around learning mathematics, but you still need to have, you know, lead these sessions. Like you still need to be able to unpack, like when you’re doing division sessions, like what does this division look like? What are the models? What are the strategies that we could really unpack? Let’s grab our curriculum. Let’s tie it to that. She’s got that because she came with some of that math background prior to being in this role. And it’s not always the case that your instructional leader has that math background. And I’ll probably argue that typically that’s not the case. But you do need, who is that significant other that can do that work with you? Like that’s the duality that other teams have, or we try to encourage if you are gonna create that type of environment in a building or a system. That’s the type of, you know, the dual role you want to strive for. You know, the bigger system you have, the more people are involved, but you do at least need to have, say, at a school site, you know, who is the instructional leader for math? And is that the same person as the facilitator that can keep the wheels turning in the right areas, in the right, in the right piece and use the right pieces to do it? So they’ve got some great things happening here. if you zoom out a little bit too, is that this is one school inside of a larger system where the system also has many schools working on similar goals, similar processes. So when you bet, you said, I’m working with this principal, but really this school system is taking part of our district improvement programs. We’re supporting the entire district on improvement. And right now, the year that we’re on with them is specifically helping instructional leaders at school sites develop appropriate school goals and have, make use of say those support structures in appropriate ways to help them achieve those goals. And that’s some of the specific work we’re doing inside this bigger system. While we’re also meeting with say the system leaders to help design the other areas like vision and goal setting and sustainability and making sure that the you know, the program doesn’t rest on one or two people’s shoulders and how are you making use of distributive leadership. So we solve these types of problems inside this, inside this district, but specifically that is paired with a number of schools inside the district to kind of do that boots on the ground school site support work as well. So that’s the work, you know, we, we, we do on a consistent basis has helped team schools, school systems, design math, planning, and what that looks like. from a high level down into the school level. If you want to get a little bit more insight what this could look like for you, we have some space available. Head on over to mcmathmoments.com forward slash discovery. We can talk about your program soon.

Thanks For Listening

- Book a Math Mentoring Moment

- Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

- Leave a note in the comment section below.

- Share this show on Twitter, or Facebook.

To help out the show:

- Leave an honest review on iTunes. Your ratings and reviews really help and we read each one.

- Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, and Spotify.

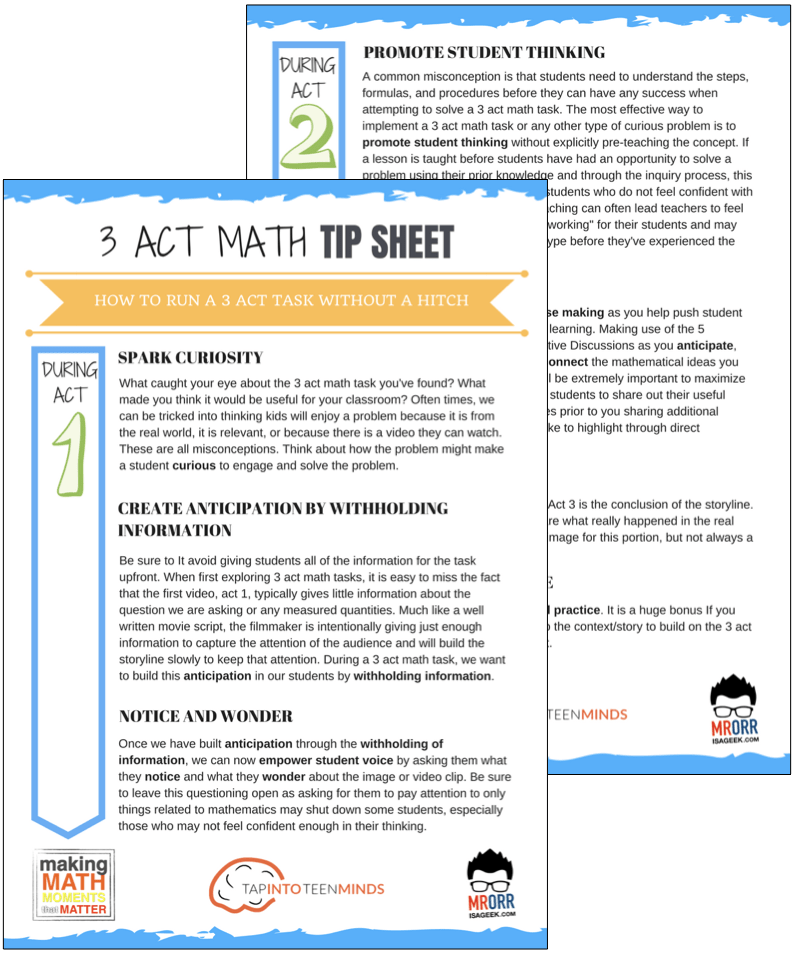

DOWNLOAD THE 3 ACT MATH TASK TIP SHEET SO THEY RUN WITHOUT A HITCH!

Download the 2-page printable 3 Act Math Tip Sheet to ensure that you have the best start to your journey using 3 Act math Tasks to spark curiosity and fuel sense making in your math classroom!

LESSONS TO MAKE MATH MOMENTS

Each lesson consists of:

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson consists of a Teacher Guide to lead you step-by-step through the planning process to ensure your lesson runs without a hitch!

Each Teacher Guide consists of:

- Intentionality of the lesson;

- A step-by-step walk through of each phase of the lesson;

- Visuals, animations, and videos unpacking big ideas, strategies, and models we intend to emerge during the lesson;

- Sample student approaches to assist in anticipating what your students might do;

- Resources and downloads including Keynote, Powerpoint, Media Files, and Teacher Guide printable PDF; and,

- Much more!

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson begins with a story, visual, video, or other method to Spark Curiosity through context.

Students will often Notice and Wonder before making an estimate to draw them in and invest in the problem.

After student voice has been heard and acknowledged, we will set students off on a Productive Struggle via a prompt related to the Spark context.

These prompts are given each lesson with the following conditions:

- No calculators are to be used; and,

- Students are to focus on how they can convince their math community that their solution is valid.

Students are left to engage in a productive struggle as the facilitator circulates to observe and engage in conversation as a means of assessing formatively.

The facilitator is instructed through the Teacher Guide on what specific strategies and models could be used to make connections and consolidate the learning from the lesson.

Often times, animations and walk through videos are provided in the Teacher Guide to assist with planning and delivering the consolidation.

A review image, video, or animation is provided as a conclusion to the task from the lesson.

While this might feel like a natural ending to the context students have been exploring, it is just the beginning as we look to leverage this context via extensions and additional lessons to dig deeper.

At the end of each lesson, consolidation prompts and/or extensions are crafted for students to purposefully practice and demonstrate their current understanding.

Facilitators are encouraged to collect these consolidation prompts as a means to engage in the assessment process and inform next moves for instruction.

In multi-day units of study, Math Talks are crafted to help build on the thinking from the previous day and build towards the next step in the developmental progression of the concept(s) we are exploring.

Each Math Talk is constructed as a string of related problems that build with intentionality to emerge specific big ideas, strategies, and mathematical models.

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Use our OPEN ACCESS multi-day problem based units!

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Partitive Division Resulting in a Fraction

Equivalence and Algebraic Substitution

Represent Categorical Data & Explore Mean

Downloadable resources including blackline masters, handouts, printable Tips Sheets, slide shows, and media files do require a Make Math Moments Academy Membership.

ONLINE WORKSHOP REGISTRATION

Pedagogically aligned for teachers of K through Grade 12 with content specific examples from Grades 3 through Grade 10.

In our self-paced, 12-week Online Workshop, you'll learn how to craft new and transform your current lessons to Spark Curiosity, Fuel Sense Making, and Ignite Your Teacher Moves to promote resilient problem solvers.

0 Comments