Episode #438: Avoid this Mistake When Teaching Multiplication: An Interview with Dr. Alex Lawson

LISTEN NOW HERE…

WATCH NOW…

In this eye-opening episode, math researcher and educator Dr. Alex Lawson challenges one of the most common approaches to teaching multiplication: introducing it as “groups of.” Drawing on years of classroom-based research, Alex reveals why this method might actually be limiting student understanding—and how rethinking multiplication through the lens of rate, quantity, and context can transform learning outcomes.

You’ll walk away with practical insights for both math teachers and coaches, including:

- Why rate is a more powerful foundation for multiplication than repeated addition

- How labeling referents helps students connect numbers to meaning

- Small tweaks you can make—even with existing lessons or resources

- What to do when students are still counting additively in grades 3 and 4

- How to build math teacher confidence in implementing new strategies

If you’re ready to deepen students’ understanding of multiplication and better support problem-solving in your math program, this episode is packed with ideas and inspiration. Press play and rethink how you’re laying the foundation for multiplicative reasoning.

Attention District Math Leaders:

Not sure what matters most when designing math improvement plans? Take this assessment and get a free customized report: https://makemathmoments.com/grow/

Ready to design your math improvement plan with guidance, support and using structure? Learn how to follow our 4 stage process. https://growyourmathprogram.com

Looking to supplement your curriculum with problem based lessons and units? Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons & Units

Be Our Next Podcast Guest!

Join as an Interview Guest or on a Mentoring Moment Call

Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

Book a Mentoring Moment Coaching Call

Are You an Official Math Moment Maker?

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Jon Orr:

Hey there, Alex, thanks for joining us here on the Making Math Moments That Matter podcast.

looking forward to digging in With you. So let us let us know a little bit about where you’re coming from here today And what’s going on a math in your neck of the woods?

Alex Lawson:

So I have been working on research and being out having a look at what that looks like in the classroom, the elementary classroom. So grade three, four is where we have been for the last few years. And now I’ve been out with the teachers to look at whether or not this is going to work in their classroom. So that’s been about. since the pandemic, it was supposed to start in the pandemic and indeed it did. We’ve got interviews with kids with masks on, but things slowed down a little bit at that point.

Jon Orr:

All right, sure, sure, awesome, awesome. Let’s talk about your math moment. When we say math class, there’s always this image that sticks in our minds and we carry with us all these years. So when I say, Alex, when I say math class, describe what is sitting in your mind’s eye right now about math class and what is that memory that you’re carrying with you all these years?

Alex Lawson:

Well, it’s actually not, I mean, I have a bunch in math class, especially when I got into teaching, but the big first math moment I remember was in our kitchen at home when I was a kid. And my brother is about five years my senior and he brought home the new textbook. And the new textbook was the one that was introduced after Sputnik was put up. And the Americans were worried about losing the arm, you know, losing the space race, etc. So it was about set theory. And I can clearly remember my father and my brother looking at each other and my brother saying, you know, dad, I have no idea what this is. And Gord looking at it and Gord going, I have no idea what it is, you’re going to have to talk to your teacher. And so, you know, it was interesting to me, because until that moment, my dad’s math was

Alex Lawson:

I always thought very strong and I think it was, but I think that the theory behind it just made no sense to him. And it didn’t mean a lot to me at that point, but later when I think back about it as a researcher, I understand, you know, sometimes we’re shooting for things that might not be that useful to teachers in the classroom and might have actually a negative impact, which is Certainly the experience of some kids at that point and my brother, he said that was it for math for me.

Jon Orr:

Right. Yeah. And he, he was like, that’s it. You know, that’s it. There’s no, there’s no more. There’s no more learning. I’ve tuned math out.

Alex Lawson:

No, he tuned math out.

He became a historian and a lawyer, but math was, no, he did not like math after that. That’s his memory.

Jon Orr:

And was that like the opposite for you going into math as a major field of study?

Alex Lawson:

It wasn’t a major field of study. My early math, the school math was, it was straightforward. I found it easy, but I didn’t love it. I liked math outside of school. I liked all the things. I liked the card games. I liked learning how to bet on the ponies. You know, whatever I was doing, the math outside of school was fabulous, but the math inside of school was uninteresting.

Jon Orr: It’s like two separate worlds, right?

Alex Lawson:

Two separate worlds, totally. And it was only because my students struggled, some of them, and I wasn’t very good at helping them that I realized I’m actually pretty interested in this and how to do a better job of it.

Jon Orr:

Yeah. Yeah.Right, right. All right, let’s get into talk about multiplication. I think it’s been a major focus of some of the work that you’ve been working on. Now, I guess here’s the question is that, does the world need more multiplication professional development? why we, because you think about it, right?

Jon Orr:

It’s been the major focus of, math. When you say math, when someone says math, they’re probably like, I’ll be honest. We’ve asked, this is episode 400 and something of the Making Math Moments a Matter podcast. And every guest over those years, we ask about their math moment. And almost, I would say, at least 300 of them are about multiplication and whether it’s always related to like math facts or around the world or mad minutes around multiplication. And so it’s like, when you think about it, it’s like, typically, multiplication is probably the most, is it the most studied, you know, basic operation in mathematics and do we need some more help here? so I guess, why focus on this?

Alex Lawson:

Okay, that’s a great question. So why bother? ⁓ And so originally, I didn’t actually want to do more on how to teach it. I just wanted to map out how do kids develop over time in a math class in multiplication and division. All I really wanted to do was to duplicate what I had done with my first book, which is just looking at kids’ videos to understand their thinking, like what is going on when they give a certain answer, in order to help teachers look at the strategies that kids are using and make sense of them, because some of them are more difficult than others, especially if you as a teacher don’t think about things that way.

But they also give us a huge amount of information. So like with addition and subtraction, we had looked at what do kids do with six plus eight? And when we look at that, or eight plus six, when we look at that, some kids have to count three times. They’ve got to count eight, they’ve got to count six, they’ve got to count from one again, and the teachers are kind of leaping at this point.

But that’s what they need to do, whereas other kids, know that they can decompose the number six and use that too, that that’ll get them to 10 and over. And that’s a much more sophisticated strategy. we, in my first work, I was just looking at that. What’s that pathway? What does it look like? And where does it go ⁓ in order for teachers to assess their kids and think about what’s next?

And that’s what I was going to do. It had nothing to do with instruction. And it was only when we started to read up an instruction that I came to the realization that maybe the way I have always taught it. And that’s why I was interested in your background, John, you know, because this might be new material for you. But the way I had always introduced it was groups of, so three groups of four.

Three groups, put four in each. But it turns out that that is, I think, actually not the best way to go for good instruction in terms of building a foundation for kids. So in terms of your question, I would have said, no, I don’t think we need any new material. We’ve got a lot of great material out there. I’ve used it. And it was only through research that I began to doubt.

the wisdom of that idea and realize that maybe there’s a better way to go about it than what we do in North America. And I have to say that’s in North America.

Jon Orr:

Right. So I think we’re all listening, like we’re all curious right now, because when you’re saying we all, we all would normally teach this as a thing about groups of, and you’re saying, let’s rethink that, tell me more.

Alex Lawson:

So what we realized, which you will know, but it’s not how we thought about it at the elementary level, is that in any word problem, my kids might learn that even if they learn their facts, they might struggle to learn their facts, but if they learn them, still, lots of them struggle with word problems. And that was the issue. We wanted a foundation that would set them up to…

do you eventually know things automatically, but be able to use them in a word problem or real life? Because what is the point of learning all that material if you can’t apply it? So when we looked at word problems, we realized, well, in any word problem, at least at the elementary, we’re dealing in quantities. So quantities meaning a ⁓ number plus a reference. So it refers to something.

So when I think of three groups of four, I’m just thinking of something as if there were no referent. But if I ask you the problem, I have three packages of gum, there are four pieces per pack. How many pieces are there? The reference in that, pieces per pack and packages, they’re all different. And so,

We realized that actually we have to pay attention to that and to start with that. what’s called the intensive quantity or you would think of it, I’m sure as rate, like what is that rate iterated? and once you do that, then all of a sudden as a, an elementary teacher, I also realized, well, that is different than addition. And this is why addition isn’t really the

I think the, mean, kids can add to multiply, but it’s not the foundation for multiplication. It’s a different thing. You know, when you’re dealing with word problems that are around addition, if you had three and four, you’re dealing with three pieces and four pieces is seven pieces. The reference are all the same. Whereas if you pay attention to them in multiplication and you’re really setting up for multiplicative reasoning, then I think you start with right or you start with that intensive quantity iterated. And that’s a different way than the way I would have taught it, which was definitely three groups, four in each group, as if it didn’t have a reference.

Jon Orr: Right, you know, because I like the fact that you’re saying we need to build rate in from the start because it’s so fundamental and because my head immediately jumped to division. You know, when you were thinking of that, it’s like when we’re saying like, if you use the words of like per and you’re saying like it’s, there’s a rate involved here in any multiplication. And then when you go to do the division, it’s like now I have like part of division, quarter division is now easily to think about. Like it makes a lot of sense to come at it from that way. And I guess like when you, are you saying like too, that if it’s not just the subtle change of, of, including the rates, cause, cause a teacher might say, well, can I say that it was like three groups, but there’s four per group is that you’re saying it’s not enough. Like we need more context to the, to the, we introduce, or is it, is it about the rate more?

Alex Lawson:

Okay, so that’s a great question and a hard question. I think it is still different than just a we. So we have built what we see again as the continuum of development. And we have kids who could do their drawing those three groups and thinking about it as four per group. But it seems subtle, but it is different to think about creating that intensive quantity and then iterating it because it is those two things together. It’s our relationship, which is pieces per pack. It’s relationship between the other two and it is the development of that relationship and really understanding that, that I think sets you up for multiplication exactly the way you talked about division. Like the setup was, you know, we could talk about more, but it was a smooth setup once you had that in place.

And it’s not that the three groups of four kids will figure, you know, if we had done that as a control, we would have had the same number of kids being equally able to solve that problem. It’s that later set up that I think is, what it does for kids. And the question would be, well, maybe it does that for kids, but maybe it’s too difficult to do. But we did not find that.

we found no, I mean, we found actually the opposite. realized that kids, when I went back to look at the old video of grade one, two kids, because I asked them the same problem. So I was really lucky. I asked them the same problem. I switched up the numbers and I made a kind of classic research error where I actually commuted the numbers by accident.

And so I had all of those situations and it didn’t matter what the problem was. The kids always start with that intensive quantity. They, before they learned multiplication, the way that we teach it, they start with that. They think, okay, well that’s four per pack and they pull out four. We have pictures of kids doing it. Either they’re concrete modeling or they just start counting on their fingers or whatever, but they start with that four, not with three and then, you know, four in each.

Jon Orr:

Right, what does that look like long term attention wise for kids as they, we introduce, if we’re going to teach multiplication and we’re going to introduce it with the idea of rate from the get go, you’re saying students are picking up on that already anyway when we’re introducing it because you think, ⁓ rates, that’s for later grades, we shouldn’t be introducing that early on. You’re saying the opposite is true with the evidence that you’ve seen. How does that, does that just naturally just keep going? Like, is it naturally like, it just gets stronger over time?

Alex Lawson:

So we’re just right now looking at 5.6 and so far yes. Like it does, it is smooth and I mean they get introduced to typical RAID in grade 5.6 anyway.

So they already have to be there and they’re already dealing with other situations where the groups of just falls apart for them. Anything that has like a continuous reference, it has measurement and later things like kilometers per hour, whatever it is, those groups of, if that falls apart for them, it falls short. So to my mind, this is a much bigger foundation more representative of what they’re going to have to do. And so far, yes, it’s looking good from, we’re just in the middle of devising the next round of lessons into five, six.

Jon Orr:

Why do you think then if it’s like, it’s naturally, we already start with it when you were saying when kids already build upon it anyway, is like, why do you think we educators, like what you were saying, when you would have taught it as groups of and drawn pictures, like you’re drawing the rate anyway, but I mean, like why exclude rate from the get go way back then?

Alex Lawson:

Did that.

Um, I think like I tried to find this research. I looked everywhere, um, in terms of finding out, well, whose idea was this? Cause I know it, you know, in other countries is not how they necessarily teach it. So I thought, somebody’s come up with this idea. I could not find the source of it. So it’s conjecture on my part, but I just think that kids, um, for whatever reason, teachers, well-meaning or people like me well-meaning, who knows? I thought it’d be easier not to have to think about those other things and just treat it as if there were no reference out there. That just, let’s just draw it. And this is the simplest drawing we can do.

Jon Orr: Yeah, that makes sense. Because I think we have a history of, we used to call them naked problems. You got to front load the material. You got to help kids just get the basics, and I’m using air quotes here, which is like no context, because context actually makes it harder, which we all know is not true. But it’s almost like math class 101 if that ever existed, it’s like for some reason when you learn how to teach math, you’re like, don’t include word problems until later. Let’s just do it abstract or before. And I guess that’s where this would come from, right? Because it’s like, you’re stripping the context, therefore you’re stripping the idea of a rate out and saying like, we’re just gonna do groups of and draw pictures.

Alex Lawson:

Yeah, and it is, I think that that’s a really good comparison. And really it’s where I got interested in things because Tom Carpenter, I don’t know if you’re familiar with his work, but he basically said, if you ask a good problem, this will help kids. It’s actually easier for them if you give them context. And he was totally right.

Jon Orr: Right. Yeah. So let’s let’s talk about teachers moves like what what as a teacher I’m listening or a lot of a lot also a lot of leaders, coaches, coordinators are listening to this podcast. So we’re helping teachers kind of make this transition. There’s probably lots of standards that don’t include this right now at that say grade levels that aren’t including rate. How do we how do we help make the transition?

Alex Lawson: I’m breathing heavily here because it’s why we ended up doing some lessons. There wasn’t a lot of material on it and I’m really, don’t, you know, it wasn’t what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to devise lessons, but I just couldn’t find the material. I’m sure it is out there. We looked at some of the Japanese material, but I didn’t, you know, go into it too deeply, but everything I saw there.

Alex Lawson:

was probably some of the material that I would want to use, but I don’t see it elsewhere. So in terms of teachers, you know, I don’t have a great answer. It’s why we wrote lessons. What else can I say?

Jon Orr:

Yeah, right, right, right. I was just thinking maybe the way that you write lessons, sometimes those fundamental practices are sometimes like, if I’m looking at my curriculum resource or my textbook right now, or I’ve got a lesson in hand, what are some of those small tweaks that I could be making to my existing resource to bring in rate earlier on? it just that I make sure that I use the context first and make sure I bring in, like say it out loud and keep reinforcing it. You know, the idea of like three packs of gum per group or know, three sticks per pack. Like just keep saying the rate as much as you can. Because we used to do that with like thinking about bringing in models as kids might not know the appropriate model to draw. But then when you emulate it on the screen, ask them to describe it, you can call out the attention to the detail and you to do that over and over again, kids pick up on that. Is that the type of moves that we make as teachers?

Alex Lawson: So that’s, so I’m glad you pushed me a little farther on that. Cause I now I do know what I want to say. Cause we had talked about this as a research team, you know, what could teachers be doing? And it is, we felt like, that the most powerful thing we were doing, we tried different things was simply labeling what the reference were in any given situation. So if you’re writing equation.

what are those things? What do those numbers mean? And really having handle on that. And you can use any resource I would say, and do that. It’s just that if they’re, the reason I was hesitating is if the resource says, you know, draw three group, empty groups, put four in each. That’s hard to change. But if what you have is, kids are resolving word problems and you’re writing out.

Alex Lawson:

the solution to the problem, then I’m gonna focus on what do each of those numbers mean. So we always set it up before, what do we know, what do we not know, what are we looking for? And we’re not even talking numbers then, we’re just talking what is it we’re actually looking for? Are we looking for the pieces, are we looking at the amount per pack? And that was the most powerful thing I think that we’re doing.

Alex Lawson:

So that you could adapt to anything except for the one situation I talked about.

Jon Orr:

Right, yeah, like I’m imagining like if you’re modeling someone’s thinking on the board or you’re modeling the question, it’s like you’re not, I think we would typically strip the context when you go to write an equation, you write the numbers, you write the sentence, right? The sentence starter or stem and I would say what you’re recommending and I think what I would do is to not strip the context.

So If I’m writing three pieces, then write, not just write three times four, it’s like three pieces times four pieces per group. Write it out and not eliminate it from the board work you’re doing or modeling you’re doing with, even if you’re drawing it, it’s like clearly label everything. It can be helpful.

Alex Lawson:

And so when you talked earlier about the transition to division, you can also achieve it with that. So if we set up the original equation, what is it we know? What are we looking for in the empty box? Like just using carpenter’s work, the empty box is what we don’t know yet. We can even label that so we know what it is. And then they just have to do the mental, optimal calculations. We do a lot of mental work.

Jon Orr:

Right, yeah, no, that’s great, that’s great. Do you think…

guess, like we always talk about, you know, one of the biggest, the biggest kind of barriers to strengthening students understanding is making sure the educators we’re working with and supporting also understand that. Like how important is that? is the exposure and then repeated like just doing math do you believe with educators like the educators themselves probably have to practice this themselves when they’re doing multiplication you know so that it can be confident they can be confident in the classroom with students.

Alex Lawson:

Totally, because they haven’t learned it this way. I certainly had not learned it this way. I never taught this way. ⁓ you know, it actually took us about a year to come to grips with the fact that this is the way we wanted to approach it. I kept resisting it. And so in terms of the teachers, we actually do a lot of word problem analysis. you know, what, and then looking at the actual equations and what type of problem is this and what are the reference and we have games that we play that they can just play with to, you know, to experiment themselves and think about it because we were out in Grand Era a couple of weeks ago and one of the teachers said, I really don’t like this. you know, missing factor multiplication. Where’s the division? I just want to do division. That’s how I think about it. So we were laughing about that and had a good discussion around it because it is a new way to think for some of us, and I’ll include myself in that, to think about division really being just all multiplication in a way. It’s just, you know, the unknown is somewhere else in that equation. But if that’s not your training, like it would be your training, but if that’s not your training, it’s hard in the beginning to think about it that way. So yeah, we spent a lot of time just playing with things and then we get to look at kids who are always, you know, a better self than me talking.

Jon Orr:

Mm-hmm.

Right? So when we’re thinking about supporting teachers who are supporting kids, what are some of the blind spots? Like, what are some of the areas that you saw didn’t work?

Alex Lawson:

So some of the areas that didn’t work in the classroom that we’re still worrying about, and I don’t know if this is pandemic or I don’t know the source of this, but we are still seeing, and the teachers are agreeing when we talk to them about this, we’re still seeing a lot of kids coming in in grade three and four trying to learn multiplication and they are still single counters.

So we always have, when we interview kids, we always do an addition item first just to see where they’re at. We don’t want to interview them and have them really have an unpleasant time in the interview. So that’s where we start. But we have kids still who need to count on for eight plus six. We even have kids who still need to do counting three times.

And it’s going to be really hard for them to learn multiplication and to take up those ideas and get in on the discussion if they’re still single counting. And I fear, worry that they will fall far enough behind that they just get given a calculator, times tables taped to their desk, and that’s it for them. That’s how I feel. ⁓ And so I worry about those kids. And I think the teachers worry about those kids. We had, we definitely had those discussions.

Jon Orr:

Yeah.Right, right. If there was one big idea, you know, want to leave with the teachers or the coaches or the coordinators listening right now, what would that one big idea, that one takeaway be?

Alex Lawson:

Well, I liked your question before and really it’s about helping kids when they’re looking at word problems, when they’re at those quantities, what is a quantity? What is it we’re looking for? And helping them to have that structured way of looking at things. So it’s not a mystery for kids what they’re trying to do.

Jon Orr:

Awesome, Alex, like you mentioned lessons, you mentioned the book, like where can, if I’m listening right now I wanna dig deeper, where can I go to get more from you, learn from you, know, learn, get access to that upcoming book, or maybe it’s out now, let us know where we can go. don’t really have any social media things. This is a complaint on the more technical people in my team, so we have none of that. so aside from the publisher, there is nowhere right now. We promise we’re gonna try, we being me. But I have nothing like that right now.

Jon Orr: Right, yeah, your team’s like, come on. Right, right. No worries, we’ll put the publisher information in the show notes so if you’re looking to learn more from Alex’s work, can scroll down in the post there and ⁓ click away and find her work. Alex, we want to thank you for joining us here on the Making Math Moments a Matter podcast and looking forward to many more conversations together. Awesome, thanks.

Alex Lawson: Thank you, John.

Thanks For Listening

- Book a Math Mentoring Moment

- Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

- Leave a note in the comment section below.

- Share this show on Twitter, or Facebook.

To help out the show:

- Leave an honest review on iTunes. Your ratings and reviews really help and we read each one.

- Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, and Spotify.

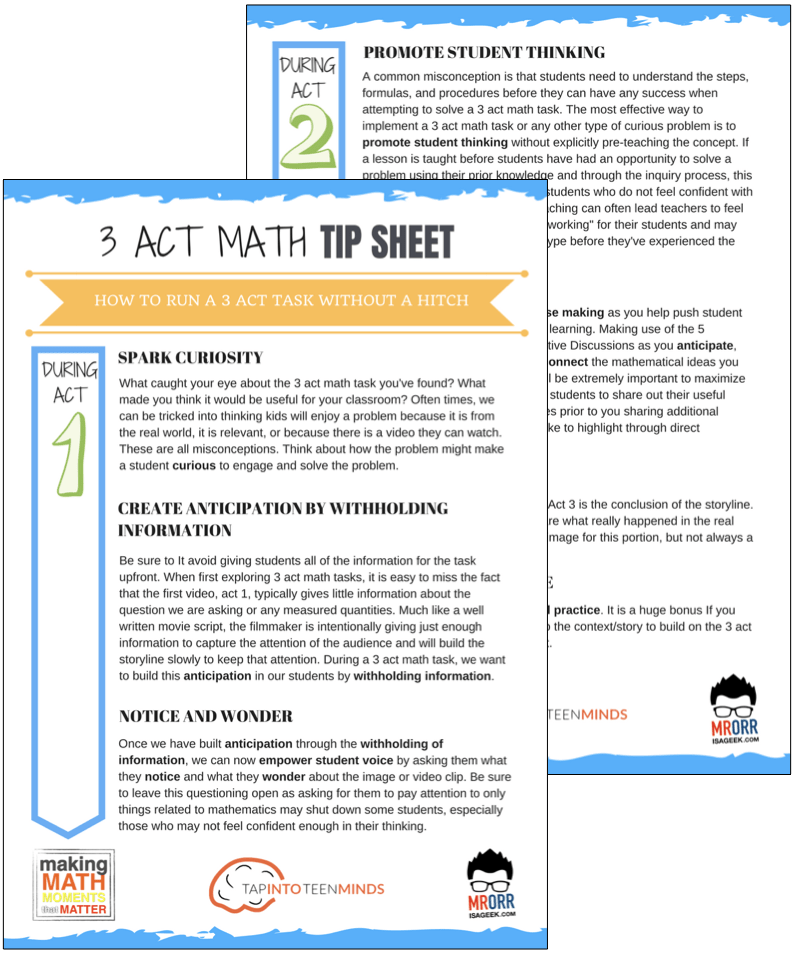

DOWNLOAD THE 3 ACT MATH TASK TIP SHEET SO THEY RUN WITHOUT A HITCH!

Download the 2-page printable 3 Act Math Tip Sheet to ensure that you have the best start to your journey using 3 Act math Tasks to spark curiosity and fuel sense making in your math classroom!

LESSONS TO MAKE MATH MOMENTS

Each lesson consists of:

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson consists of a Teacher Guide to lead you step-by-step through the planning process to ensure your lesson runs without a hitch!

Each Teacher Guide consists of:

- Intentionality of the lesson;

- A step-by-step walk through of each phase of the lesson;

- Visuals, animations, and videos unpacking big ideas, strategies, and models we intend to emerge during the lesson;

- Sample student approaches to assist in anticipating what your students might do;

- Resources and downloads including Keynote, Powerpoint, Media Files, and Teacher Guide printable PDF; and,

- Much more!

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson begins with a story, visual, video, or other method to Spark Curiosity through context.

Students will often Notice and Wonder before making an estimate to draw them in and invest in the problem.

After student voice has been heard and acknowledged, we will set students off on a Productive Struggle via a prompt related to the Spark context.

These prompts are given each lesson with the following conditions:

- No calculators are to be used; and,

- Students are to focus on how they can convince their math community that their solution is valid.

Students are left to engage in a productive struggle as the facilitator circulates to observe and engage in conversation as a means of assessing formatively.

The facilitator is instructed through the Teacher Guide on what specific strategies and models could be used to make connections and consolidate the learning from the lesson.

Often times, animations and walk through videos are provided in the Teacher Guide to assist with planning and delivering the consolidation.

A review image, video, or animation is provided as a conclusion to the task from the lesson.

While this might feel like a natural ending to the context students have been exploring, it is just the beginning as we look to leverage this context via extensions and additional lessons to dig deeper.

At the end of each lesson, consolidation prompts and/or extensions are crafted for students to purposefully practice and demonstrate their current understanding.

Facilitators are encouraged to collect these consolidation prompts as a means to engage in the assessment process and inform next moves for instruction.

In multi-day units of study, Math Talks are crafted to help build on the thinking from the previous day and build towards the next step in the developmental progression of the concept(s) we are exploring.

Each Math Talk is constructed as a string of related problems that build with intentionality to emerge specific big ideas, strategies, and mathematical models.

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Use our OPEN ACCESS multi-day problem based units!

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Partitive Division Resulting in a Fraction

Equivalence and Algebraic Substitution

Represent Categorical Data & Explore Mean

Downloadable resources including blackline masters, handouts, printable Tips Sheets, slide shows, and media files do require a Make Math Moments Academy Membership.

ONLINE WORKSHOP REGISTRATION

Pedagogically aligned for teachers of K through Grade 12 with content specific examples from Grades 3 through Grade 10.

In our self-paced, 12-week Online Workshop, you'll learn how to craft new and transform your current lessons to Spark Curiosity, Fuel Sense Making, and Ignite Your Teacher Moves to promote resilient problem solvers.

0 Comments