Episode #353: Math Rules That Expire: Rethinking Math Tricks & Shortcuts for Long-Term Understanding

LISTEN NOW HERE…

WATCH NOW…

This episode explores the concept of “expired math rules or math tricks”—rules, tricks, and shortcuts commonly taught in early mathematics that become problematic as students advance in their learning. Based on the article 13 Rules That Expire by Karen S. Karp, Sarah B. Bush, and Barbara J. Dougherty, the discussion highlights how overgeneralizing strategies, using imprecise vocabulary, and relying on procedural tricks can lead to misconceptions. The conversation emphasizes the importance of fostering deep mathematical understanding rather than rote memorization of rules that don’t hold true in all contexts.

Key Takeaways:

- Many tricks (e.g., “you can’t subtract a bigger number from a smaller one”) work in early math but break down with more advanced concepts like negative numbers.

- Teaching why math works builds deeper understanding and helps students apply knowledge flexibly, rather than relying on rules that later fail.

- Imprecise wording (e.g., “always move the decimal when dividing”) can cause confusion when students encounter different representations of numbers.

- Encouraging reasoning and sense-making allows students to adapt their thinking to new problems, rather than getting stuck when a memorized rule no longer applies.

- By recognizing these expired rules, educators can modify instruction to prioritize reasoning and problem-solving over rote tricks.

Attention District Math Leaders:

Not sure what matters most when designing math improvement plans? Take this assessment and get a free customized report: https://makemathmoments.com/grow/

Ready to design your math improvement plan with guidance, support and using structure? Learn how to follow our 4 stage process. https://growyourmathprogram.com

Looking to supplement your curriculum with problem based lessons and units? Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons & Units

Be Our Next Podcast Guest!

Join as an Interview Guest or on a Mentoring Moment Call

Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

Book a Mentoring Moment Coaching Call

Are You an Official Math Moment Maker?

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Yvette Lehman: So today we are diving into an article that I read recently and I shared with both of you, The 13 Rules That Expire, and it was written by Karen Carp, Sarah Bush, and Barbara Doherty. And I think I stumbled upon this article through a conversation with a coach when we were talking about the fact that sometimes we unintentionally create misconceptions or cause confusion around the behavior of math because we’re trying to teach kids a trick.

rather than taking the time to support their understanding. And so we’re gonna kind of dive into the, maybe the risk of some of these rules that expire. So the article is called 13 rules that expire. And it’s like, what happens when we overgeneralize something, particularly in early mathematics? And then that rule just is no longer true. Like the behavior doesn’t hold. And like, does that do more harm than good?

Kyle Pearce: Right, right. And I love this article. I love, want to, before we dig in, we picked a couple that we want to chat about here today. I want to talk about, you know, sort of like the harm in how we often do things. This isn’t just in math, but specifically in math class, it happens quite a bit where, know, we’re sort of like, we’re sort of brushing things off that are fairly complex as just sort of like, just accept it and move on and implement them as is. Right? So it’s kind of like when a you know, as a parent and you know, my kids are a little older now, but you know, when, kids are asking questions and you’re just sort of like, I just don’t have the time to explain to you. So you just sort of say, well, it is because it is, you know, and it’s like the, the more we do that in math class, or really what I should say, the opposite is true is like, we need to do that a whole lot less so that students don’t just show up to math class thinking that they’re just going to be told a rule without any sort of explanation because

when we like zoom out a and we ask ourselves and we wonder why so many kids say like math doesn’t make any sense to me. It’s because of all of these instances where we just didn’t have enough time or we didn’t have enough patience or maybe we just didn’t have the knowledge, right? The content knowledge ourselves to know why some of this stuff is true and it really perpetuates the negative sort of view that many people have adults and children everywhere around what math is and whether it actually does make sense or not or whether it’s just certain people will get it and other people really won’t. So I think it’s really important for us to at least address that because it’s not just these 13 rules. It’s like all the other things we do day after day when kids are asking questions. We need to make sure that we’re doing our best to support their understanding.

Jon Orr: Right, and think you hit the nail absolutely on the head is that most people, human beings in general, think math is a bunch of rules and tricks to follow. And we just have to know those tricks and memorize those rules. And we have to somehow miraculously figure out which is the right rule to apply to this situation. And this is typically how we’ve taught math in the past as a society.

is that, hmm, this is the rule that applies here. This is how you recognize the scenario so you can apply the right rule and not focused on the understanding. And the other thing you said, you know, is taking the time to make sure that we talk about the why or what’s really happening under the hood here. And I think you’re also right, is like, I think most of us just didn’t know. You know, we just don’t, we didn’t know that that, because we came from the tips tricks society of like, this is the way we viewed math.

And until we take the deep dive to say like, actually am going to slow down. I actually am going to make sure that I understand this. And so that I can then convey that to my students. We will always be a tips and tricks math society until we realize that that’s what we have to do. You have to take time. You listening right now to this podcast is you taking that step saying like, I’m actually going to hear this and maybe you know these, but maybe you don’t, but maybe you will after this.

Yvette Lehman: So we’re going to dive into, I guess we’ll call them, you know, the ones that jumped out at us from this article. And I picked the first one. And the rule is when you multiply a number by 10, you just add zero. So, so then I thought the article was great because they said, you know, when is this not true? So can you think of a situation where like that’s not true when you multiply a number by 10, you don’t just add zero.

Jon Orr: Isn’t that the real

Kyle Pearce: Mm, I love it. I’m thinking like decimals, you know, which, which I think, unless you realize that, you know, there’s something to think about there, like, I could see how many people would just go with it, you know, you just roll with it.

Yvette Lehman: Right, for sure. Yeah, so if I multiply…

Jon Orr: Well, otherwise you’re at, which way do I add the zero now? You know, if I multiply, if I’m multiplying a decimal by 10, like the zero’s going so, like now I’ve added another rule to follow if I still treat that rule as a

Kyle Pearce: I also don’t like the use of the word add in there just because it’s like if it’s not already confusing enough for kids when they’re like the four operations and which like what is adding what is multiplying what is it’s like wait a second so when you when you multiply you’re adding a zero like it’s like wait you know it just adds one more level of complexity to a rule that event you know is is gonna break for us here.

Yvette Lehman: Well, the other one that I think goes hand in hand with this one is when people say, just move the decimal. I think that one is even harder for me. think John and I were in an Uber and the Uber driver said, just move a decimal. And I responded, did you know that the decimal doesn’t actually move?

Jon Orr: I remember that the guy was like, yes, I said the wrong thing. Now I’m going to get a lecture.

Yvette Lehman: No.

Kyle Pearce: He just pulls over and says, get out, you know? And now you gotta go find a new Uber, but.

Yvette Lehman: Yeah, yeah. Well, you know, and I’m guilty of using that rule as well. You know, I was teaching students to multiply by 10, 100, and 1000, and I’d say, you know, shift the decimal. But in reality, it’s like the decimal’s not moving. The digits are shifting a place in our place value system. So the decimal stays where the decimal is between the ones and the tenths.

Jon Orr: I don’t even like the shifting because it’s like it just saying like this thing you’re looking at, this representation of this number actually like moves. And I’m like, doesn’t seem like the right idea here. Right, right.

Yvette Lehman: see, I’m going to defend it. I’m going to defend it. Yeah, but I that’s sure, but I’m going to defend that statement. So are you ready? Okay. So if you understand that we have a base 10 place value system, right? So like if you understand, and that goes back to also understanding that the symmetry of our base 10 system is around the one, not the decimal.

Kyle Pearce: Right. You’re like it got 10 times bigger or 10 times smaller and there’s no way around it. Ooh, all right. Yeah.

Jon Orr: okay, ooh, we got a math fight.

Yvette Lehman: So like if I think about the one in our place value system, to the left of it is 10 times greater, to the right of it is a 10th. And so my idea of like the fact that the digits are moving over one place implies that every digit is like, every position is going to be 10 times greater. If we understand that we have a base 10 system and that our base 10 system allows us to look at this multiplicative comparison between quantities, that it’s know 10 times greater or a tenth the size depending on if you’re looking to the left or the right of one but knowing that one is like the center of our base 10 system and that basically you know we’re multiplying by 10 then multiplying by 10 times 10 then multiplying by 10 times 10 times 10 I think I feel more comfortable using the language like we’ve moved it over a position in the in the place value system

Kyle Pearce: I think you just blew some minds with the whole idea of symmetry around the ones.

Jon Orr: I think so too. I remember hearing you say that a while ago and I was like, you’re right. I never really thought about it.

Kyle Pearce: Right, like, and I think everyone fixates on the thing that looks different, which is the decimal, right? And we talk always about shifting decimals and moving the decimal. And really what it is, is it’s everything around that ones column, which makes a ton of sense when you think about whole numbers. Like, it’s like, you know, the one whole is in that column, 10 holes. Well, I guess it’s no longer in that column anymore. Nine holes would be in that column. But the part that what you just described, Yvette, which I think is,

different than saying, just saying like shifting is that you’re actually allowing like students to actually build the behavior that makes it seem as though things are shifting around, which they are. And you know that if I multiply something 10 times bigger, that all the digits are going to appear to have shifted, you know, left or right, right? And I really like that as long as it’s built off of the behavior of how the place value system works. which I know you’d be in supportive. But I see John, it looks like he wants to dig in here.

Jon Orr: It’s just, think the language, right? So it’s like, yes, that’s the visual representation of what this structure allows us to do. But I’d rather discuss what’s actually happening, right? Like I’d rather say, like when you’re saying it’s 10 times bigger, yes, the visual representation is, and appears to be a shift. But really what you’re saying is like, I’ve just taken the 10s digit, you know, or this 10s digit space and I’ve blown it up. This is, if you think about like James Tanton in Exploding Dots, like he…

part of that it was like a really interesting thing to think about. It’s like, we have too many here and when we multiply by 10, we’re 10 times bigger, we’re gonna like, we’re gonna put one here, we’re gonna blow that thing up by a factor of 10, which means we get one, you know, we move up one more here in this space. To me, it’s not a shift, it’s an explosion here. And yes, it’s visually, it’s visually appears as a shift, but that’s a representation of what’s

Kyle Pearce: Right. So John, you wanna maintain the, know, sort of the integrity of like what’s happening in the background, you know?

Jon Orr: Right, otherwise we’re still talking about tips and tricks. Shifting is still an implying I’m shifting this, which means I’m using some sort of trick here because what mathematical thing is a shift? Like we shift graphically, we shift geometrically, but it’s like, are we shifting the number system?

Kyle Pearce: like it. Right, right. I like it. Friends, those listening right now, still listening, hopefully they’re still with us, you will recognize that in math, this is very healthy. So I want you thinking about this when you go back and you go into your departments and you’re in your schools or in your district, these are the types of discussions that allow you to get more clear about what’s happening with the mathematics, which is the most important part.

So I’m seeing both sides. I’m gonna act like Switzerland here. I’m kind of neutral here. I see both sides and I like both. And I like the argument that both people are making here. And the beauty is, is that as long as we go back into the classroom and we’re trying to help students to also have this opportunity, like think of the discussion that could evolve with kids, you know, like with kids in a grade where maybe they already know this quote unquote rule that expires.

to challenge them to have this discussion. So I think there’s a lot of really good opportunity there. Let’s move on to our next one friends. And I’m gonna go ahead and I’m gonna pick the one that jumped out at me and it’s you always divide the larger number by the smaller number. And I vividly remember doing this as a kid, especially, and this one gets confusing in so many places because first of all, I remember also as a kid not knowing

with the traditional division sign, you know, which later in life made me recognize, I’m like, the division sign’s kind of like just a fraction sign. Like it’s like a number over a number. I like never really put that together, but I always got confused as to which number I was supposed to put first versus last, but then the same is true even if you write as a fraction, you know, like more people would see that, okay, it’s this number divided by this bottom number and that’s fine, but think of what that tells kids.

about division like it suggests that we can only take big things and divide them into small chunks or we’re taking a number of things and we’re trying to put them in groups of like now we’re going down the land of part part of and quoted of division there’s so much wrong about this statement that’s incredible because even if like basically what we’re saying is like if there’s one cookie and I have my friend over like I am sorry.

Jon Orr: Right. What’s your favorite?

Kyle Pearce: I cannot divide this with you. get the whole cookie, which works in my favor. I get it. I love it. But I mean, that other kid is probably going to say my math rule is wrong because we can divide that cookie. That one cookie can be divided amongst two people, one divided by two. And it does give us a fraction and a decimal, but a fraction of one half. So pick away at this one. What else are you liking or not? I don’t think there’s anything to like about the rule. What are you also seeing as maybe inherently an issue here?

Yvette Lehman: I think you made such a great point that I wasn’t necessarily thinking of, like this idea that we can reveal our understanding of fractions through fair share scenarios. So like in the Ontario curriculum, that rule should be never existing because it’d be as early as grade one, start introducing fractions as the result of fair share scenarios. Exactly what you just described. have, you know, two cookies divided by three people.

So right away we’re already, you know, revealing this relationship. But it also made me think about, I talk about this all the time, how I think that one of the biggest and maybe missed opportunities in elementary mathematics is multiplicative comparison that goes both ways. So for example, know, students often can articulate that 15 is three times greater than five, but they rarely articulate that five is one third of 15.

And that is also that division. It’s division revealing a scale factor. So 15 divided by five is three. That’s the scale factor. But five divided by 15 is one third. That’s a scale factor. And that multiplicative comparison where we’re looking at the relationship between two quantities both ways is another time that we really should be exposing students to scenarios where we’re dividing, let’s say, a smaller quantity by a larger quantity. So I think we’ve basically just like blown up this rule. Like I just don’t

Kyle Pearce: 100%. And you think about how many, like, and I know this is happening in multiple different curriculum, which is standards, we’ll call it, for our American friends. This comes in many different places where we talk about these inverse operations and the importance of students becoming fluent and flexible with inverse operations. But the multiplicative scale factor is so key there, but so underutilized. And we have this heavy reliance, right?

You know, we like counting up. We don’t like counting down. The same is true when we scale. We like scaling in the up direction. We don’t like scaling down. Or when we do, we often say divide it by a number. We don’t actually multiply it by a fraction, which I think is something that we’ve unpacked in our proportional relationships course inside the academy. That is such an important move for teachers to become flexible with so that students can become flexible with it.

Like you had said, Yvette, it’s not even like number six here on this list, which is exactly what we’re describing here, won’t actually happen because it won’t, you won’t be able to, you know, if you actually focus on this a little bit earlier.

Jon Orr: Yeah, we talk about that too in our monthly sessions where we’re unpacking, know, unpacking and building capacity series. We had specifically talked about division and unpacking how to think about division. Yvette, you’ve always said it’s like, if we should be really speaking, if we’re dividing, you know, if we’re dividing by this, we should really be always incorporating the multiply by the, you know, multiply by that reciprocal fraction in that same language, which helps with this understanding. All right, let’s.

Let’s move on to number nine. I picked number nine, folks. And I have a feeling that number nine may be more controversial for more people because I think there’s lots of people that are like, isn’t that a rule? And I’m gonna argue hard against this rule. And part of it is like, think me as a high school teacher, and I think where the, and I’ll say the rule in a sec, but I mean.

Kyle Pearce: or conventional, you know?

Jon Orr: me as being a high school teacher and I think where the rule comes out is I think many elementary teachers think this is the rule at high school and therefore thou shalt always do this with numbers. So here’s the rule, improper fractions should always be written as a mixed number. So if we end up with an improper fraction, we have to, we have to, it’s wrong. And I know that teachers have marked kids wrong on this by.

not leaving it as an improper fraction and they must write it as a mixed number. I’m gonna hold back my emotional response here folks. And I want you guys to comment on this. I’m gonna let you guys comment here and then I will weigh in.

Kyle Pearce: It doesn’t sound like it, John. It’s creeping through. Well, want Yvette, you I want to hear from you because you come from the elementary side of things, right? Teaching a lot of grade six and you know, yeah, like was was this a thing or you know, did you get there yet? Like what was going on in your world?

Jon Orr: Was this a rule for you, Yvette?

Yvette Lehman: So I would definitely say that that was probably something at one point that I insisted, you know, that on an assessment students, but I think that’s because I taught, you know, typically up to grade six and seven, and we weren’t operating with fractions a lot. You know, it’s almost like when they just start to operate with fractions, particularly in the old Ontario curriculum. And so because at the time, the fractions were a result and then we didn’t do anything with them necessarily, we would just represent them as a mixed number. But as I went on my own math journey and realized that when I’m operating with a fraction, I actually want to be flexible. Like there’s some times, like the other day I actually had a scenario, I was multiplying five sixths by one and a half.

and I found it easier in that scenario to multiply 5 6 by one and a half because I decomposed like the one and a half. So then I was like, I just have one five six and then I have a half of five six. But then there are like other scenarios where the having the improper fraction is better. And I guess what I want now is the choice.

Kyle Pearce: Right. I love that. I wasn’t going to come at it from the actual, I guess, flexibility perspective. But ultimately, it is really that in that we want to make sure students can move back and forth. And really, what we want them to be able to do is to make sure that they’re confident in what that thing even represents. Like you had said, sometimes,

A mixed or an improper fraction might be like super, super not so friendly to to look at, right? However, it’s like more important than what the representation is, whether it’s mixed or improper, is looking at it and being able in your mind to get a sense of what that number even means. I’m to pick something super ugly. 43 37th, you know, I’m picked, picked that number and it’s like, I mean, I could I could make it a mixed number.

But more important than making it the mixed number, I think is in my mind going, this is a little bigger than one. And like there’s a little extra, which you get by getting the mixed number. And I think that’s the goal. Like that was probably the initial goal of like why they were always asking kids to always do this was we’re hoping that when they looked at a number, they were flexible enough, like Yvette saying, to kind of know what it means. The problem is the way we approach it, especially when we say like, you always have to, thou shalt.

is that what usually kids end up doing is they end up doing this little bit of tricks. They come up with the number and they still aren’t thinking about the number, right? Like, so even though it comes out as a mixed number, they’re not even in their mind envisioning what that means, right? So I like the flexibility part, but of course, you know, I think it really, you know, what would be better, I think, is asking a student why they wanna keep it as a mixed or improper fraction in this case. Like think of the power of that.

choose what you’d like to or how you’d like to represent it and why you think that’s a better representation for this context. Think about what the kids have to now do. And they have to probably they have to do it anyway, right? So you got the goal where you got them to do it and practice it. But now they actually have to go, you know, I actually understand what these two numbers mean. And I like to describe it this way over that.

Jon Orr: Yeah, I’m to build on the flexibility part. For me is, I don’t know, you’ll have to decide. the, you know, on the flexibility side for sure, because I completely agree with you that we want students to make that choice. then, you know, like when we think about if we’re going to take that number and do something with it, like first, like, do we can we interpret what this means? So sometimes moving to a mixed number helps you interpret the meaning of the number.

Kyle Pearce: With or without a motion, OK. Just making sure.

Jon Orr: more so than what the same proper fraction was. But if I’m going to take it and run with it, then I want to be able to like, I have to convert it back, right? And it’s like, if I’m going to do anything with it, I could convert it back. Now I could be flexible why not converting it back as well. But when we get up in grades as well, this is where my like high school part came from, comes from, is that, is that if we’re going to say, write it in any sort of linear relation, that’s all of a sudden it’s like, no one’s writing this in a mixed number.

I do want to also tie the flexibility back to say, you know, Shelley Yearley and Tara Flynn’s work on on rethinking fractions with Kathy Bruce, like, and the unit fraction and counting with unit fractions, like think about nine fifths is, you know, if we’re going to compare nine fifths and 10 fifths, you know, like I’m nine fifths, 10 fifths, 11 fifths, leaving them in improper fraction helps with our understanding of like how they relate to each other and counting.

and counting by unit fraction or nine one fifths, right, or 10 one fifths. And then and I like to stretch that because when we get into higher level mathematics, we don’t write them as mixed numbers. That I’m thinking about trigonometry and thinking about radian measure of trigonometry. And I think about the unit circle and we’re counting by seven pi over four or pi over four. It’s like we use the unit fraction to count. So seven pi, you know, eight pi over four. Like we don’t write them in

in mixed number, we leave them in improper fraction form. And this is just the common standard at that point. So if we build all that together and think about what we’ve all been saying is like we’ve talked about flexibility, we’ve talked about say, students to the interpretation and do I want to be able to go between the two? Like going between the two is essential as a strategy, like an important skill to know so that we can be flexible. But then if we think

And this is the myth part, I think, right? Is if we think we’re doing the service of like making sure we always go to a mixed number because the next grade needs it that way, that’s the myth. Like don’t sell yourself on that being the real reason that we’re doing this. And I think we do that a lot in education is we think we’re preparing them for the next grade instead of just preparing them.

Yvette Lehman: So I’m thinking about, you know, as a teacher, if like we said, our own math experience relied on these rules or these, you shortcuts, what experiences do teachers need to position themselves to going back to what Kyle said, like answer the why.

You so it’s really about being able to, I know you said, you know, like my son asked me these questions all the time, like why, you know, and you’re right. Like it’s like, sometimes we want to brush it off or dismiss it because it’s like, it’s hard or we don’t have the time, but just like keeping yourself accountable to never do that in the math class. Even if you don’t know why to, in that moment, being willing to find out.

Kyle Pearce: I love that.

Jon Orr: You commit to it. You commit to it.

Yvette Lehman: So like you never, never dismiss it. So somebody, if you have a rule, let’s say your rule is, know, multiply, when you multiply by 10, you add a zero and a student says, why? And is that always true? Being willing to actually dig into that and answer that question.

Jon Orr: Well, and not not saying it’s gonna derail my lesson, right? Because it’s like, I remember being in the class and a kid would say a rule that was like, I just cringe at them saying that it’s like, I’m going to stop everything right now. And we’re going to address this, make sure that we address this maybe myth or this, this this common misunderstanding at this point, and their understanding so that we can like, go back. if it like it takes me 15 minutes to go down that pathway, it’s worth it.

Kyle Pearce: Right. And you know what it comes down to again, my favorite word is vulnerability, right? Like you have to have to have to be okay with not knowing the answer. And my son still, you know, he’s very like he’s 10 years old and just, I think he’s, we always say Leto and Lando are very similar. You know, he brings up things that sometimes I’m like, I don’t know if you’re making this up, you know, like, I don’t know if you actually know this or if, you know, and I’m like, I actually don’t know the answer. And, you know,

But it’d be cool for us to figure it out. It’s not just math. Sometimes it’s things about how, you know, like why the sun looks this way or why that, you all these random things kids ask, it’s okay to not know the answer. And I think staying curious enough and when kids, truly believe, and I have no data to support this, but when a student asks you a question and you’re willing to pause and kind of look up to the sky a little bit and like think about it,

I think you’re validating that student so that they know it’s like, wow, like I actually have some good thinking here. Whereas when we sort of push it off, when we take these ideas and we sort of like say, like, here’s the answer, think of what that tells the student. They’re like, well, that must have been a dumb question. You know, you didn’t say it, but your actions sort of suggested that it’s not a worthwhile question.

And therefore, we’re going to dismiss this thing. And you just think of what that does to a student when we talk about, the other hand, we want more math discourse. We want kids talking and communicating. We want them thinking. Well, when kids are thinking, for us to find ways to at least validate what it is that they’re curious about and to make them feel good about it at the same time so that they continue to want to do the thinking in our math classes, I think is really key here.

Jon Orr: So, you know, said something, you know, just a few minutes ago about like, what are we committed to doing? Like, what are we doing to know that this is an important move for us? You know, and also if I’m a leader of mathematics, I’m a coach, I’m a coordinator, and I’m planning professional development, then, you know, an easy move is to get the article. We’ll put the article in the show notes. You may have already seen the article. Maybe you’re like, I read that. Have you used it? Like, have you picked one?

And every time you started a staff meeting or every time you started a PD session, you unpacked or put them in table groups to have a conversation about, you know, whether this is true or false and what we think about it and unpack that rule. Because we know when we as educators do more math with each other as adults, we learn and we get we build our capacity and building capacity is one of the six components of an effective mathematics classroom. There are there are six. And if you if you haven’t, say,

taking a deep dive into those six and got your free report on the six and where you stand on the six in terms of your classroom, can head on over to makemathmoments.com forward slash report and answer a few questions and we’ll kind of mail you, we’ll mail you that report so that you can understand the six but also improve on the six. But building capacity is one of the six and it’s one of the linchpins of like how to do or how to allow us to do what we can do easier, more effectively in the classroom is building our own capacity.

So this is what we wanted to do here is to really help you build a capacity, but as a teacher, but as a leader, make sure we’re focusing on building the capacity of our educators and take this article and put it into place in terms of your strategies moving forward.

Thanks For Listening

- Book a Math Mentoring Moment

- Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

- Leave a note in the comment section below.

- Share this show on Twitter, or Facebook.

To help out the show:

- Leave an honest review on iTunes. Your ratings and reviews really help and we read each one.

- Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, and Spotify.

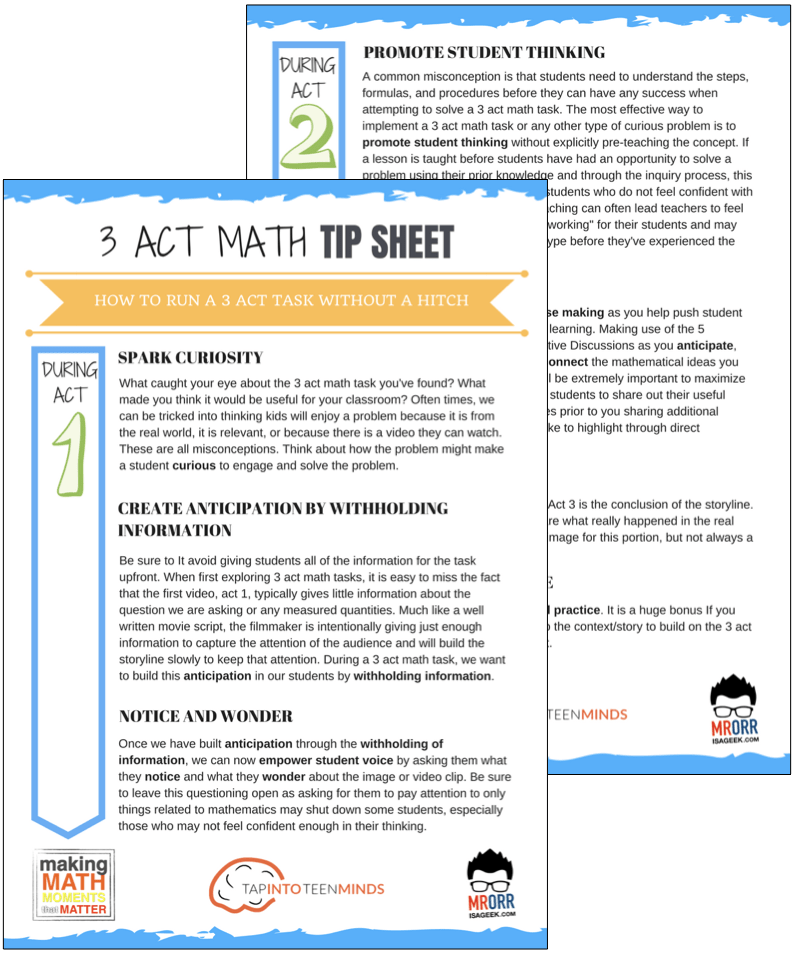

DOWNLOAD THE 3 ACT MATH TASK TIP SHEET SO THEY RUN WITHOUT A HITCH!

Download the 2-page printable 3 Act Math Tip Sheet to ensure that you have the best start to your journey using 3 Act math Tasks to spark curiosity and fuel sense making in your math classroom!

LESSONS TO MAKE MATH MOMENTS

Each lesson consists of:

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson consists of a Teacher Guide to lead you step-by-step through the planning process to ensure your lesson runs without a hitch!

Each Teacher Guide consists of:

- Intentionality of the lesson;

- A step-by-step walk through of each phase of the lesson;

- Visuals, animations, and videos unpacking big ideas, strategies, and models we intend to emerge during the lesson;

- Sample student approaches to assist in anticipating what your students might do;

- Resources and downloads including Keynote, Powerpoint, Media Files, and Teacher Guide printable PDF; and,

- Much more!

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson begins with a story, visual, video, or other method to Spark Curiosity through context.

Students will often Notice and Wonder before making an estimate to draw them in and invest in the problem.

After student voice has been heard and acknowledged, we will set students off on a Productive Struggle via a prompt related to the Spark context.

These prompts are given each lesson with the following conditions:

- No calculators are to be used; and,

- Students are to focus on how they can convince their math community that their solution is valid.

Students are left to engage in a productive struggle as the facilitator circulates to observe and engage in conversation as a means of assessing formatively.

The facilitator is instructed through the Teacher Guide on what specific strategies and models could be used to make connections and consolidate the learning from the lesson.

Often times, animations and walk through videos are provided in the Teacher Guide to assist with planning and delivering the consolidation.

A review image, video, or animation is provided as a conclusion to the task from the lesson.

While this might feel like a natural ending to the context students have been exploring, it is just the beginning as we look to leverage this context via extensions and additional lessons to dig deeper.

At the end of each lesson, consolidation prompts and/or extensions are crafted for students to purposefully practice and demonstrate their current understanding.

Facilitators are encouraged to collect these consolidation prompts as a means to engage in the assessment process and inform next moves for instruction.

In multi-day units of study, Math Talks are crafted to help build on the thinking from the previous day and build towards the next step in the developmental progression of the concept(s) we are exploring.

Each Math Talk is constructed as a string of related problems that build with intentionality to emerge specific big ideas, strategies, and mathematical models.

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Use our OPEN ACCESS multi-day problem based units!

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Partitive Division Resulting in a Fraction

Equivalence and Algebraic Substitution

Represent Categorical Data & Explore Mean

Downloadable resources including blackline masters, handouts, printable Tips Sheets, slide shows, and media files do require a Make Math Moments Academy Membership.

ONLINE WORKSHOP REGISTRATION

Pedagogically aligned for teachers of K through Grade 12 with content specific examples from Grades 3 through Grade 10.

In our self-paced, 12-week Online Workshop, you'll learn how to craft new and transform your current lessons to Spark Curiosity, Fuel Sense Making, and Ignite Your Teacher Moves to promote resilient problem solvers.

0 Comments