Episode #356: Instructional Recipes For Teaching Math

LISTEN NOW HERE…

WATCH NOW…

Have you ever wished for a simple yet effective way to improve math instruction without overwhelming teachers?

Many educators struggle with making math lessons engaging, equitable, and effective. Without clear guidance, teaching methods can vary widely, leading to inconsistent student experiences. But what if there was a structured, research-backed approach that empowers teachers while ensuring high-quality instruction for all students?

You’ll learn:

- Discover how instructional recipes provide clear, research-based strategies that simplify lesson planning while enhancing student engagement.

- Learn how small, high-leverage instructional changes can lead to significant improvements in student understanding and classroom equity.

- Gain insights into practical teaching techniques, including effective task launches, student discourse strategies, and how to provide hints and extensions without lowering cognitive demand.

Tune in now to explore how instructional recipes can transform your math teaching approach—giving both you and your students a more rewarding experience!

Attention District Math Leaders:

Not sure what matters most when designing math improvement plans? Take this assessment and get a free customized report: https://makemathmoments.com/grow/

Ready to design your math improvement plan with guidance, support and using structure? Learn how to follow our 4 stage process. https://growyourmathprogram.com

Looking to supplement your curriculum with problem based lessons and units? Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons & Units

Be Our Next Podcast Guest!

Join as an Interview Guest or on a Mentoring Moment Call

Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

Book a Mentoring Moment Coaching Call

Are You an Official Math Moment Maker?

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Jon Orr: Hey there, Thomas, thanks for joining us on the Making Math Moments That Matter podcast. We’re you know, I’m excited to dig in. I’m. I’m intrigued, about some of the topics we’re going to talk about here today. And I know that our listener, is going to be intrigued as well. But before we dive in, you know, take a moment like let everybody know where you’re coming from. What’s your role in education and, and what’s going on in your world right now?

Thomas Nobili: Thanks, John. Again, thanks for having me on. Glad to be here and talk. Talk math. One of my favorite things to talk about, my name is Tom Mobley. I come from Connecticut. So East Coast, the US live in a town about, hour, hour and a half north of New York City. So to give people a sense, and, yeah, I’ve had many roles in education currently.I am a consultant. I do some work for a educational nonprofit here in the state. And then I also have my own, math consulting company as well that I’ve recently started and trying to build up a little bit.

Jon Orr: Gotcha, gotcha. Well, the question we ask everybody is about your math moment. So when you think back, you know, your your history of math, usually it’s a moment that when we say, like math class, something pops in your, your mind like, it’s like you can’t help it when you hear the word like this image, that, kind of that maybe you experienced, but also kind of stuck with you throughout the years. But when I say math class, like, what moment comes to mind?

Thomas Nobili: Yeah. You know, thinking about this question because I know it’s, it’s one that, is always asked on the show. And, you know, it’s interesting because I was thinking it was, like, hard for me to pin down a specific moment, where I felt like there was something really kind of like, you know, seminal about it. I feel like a lot of my math class experience, which is kind of like a blended law above kind of the same.

Kind of the same type of just like very passive experience. I mean, where, you know, it was about getting getting the right answer and. Necessarily, I mean, I guess one that really sticks out that I, you know, if I had to pick and when I was a sophomore, you know, took geometry and I remember that the teacher, it was like we would just come in, we’d have an assignment, we’d have to, you know, do it.

And if we had any questions, her answer was always, well, it’s in the book. And so and again, I really didn’t want to pick a negative one, but I it was just like and I wouldn’t say it was a scarring experience or anything. It just there was nothing that really, you know, just kind of all just like, okay, this is math.

You come in and I was always okay at it, did fine, was able to memorize stuff, but I, you know, I just didn’t really, it just wasn’t really anything that that did anything for me until I started getting into teaching it. And then that’s when it really opened up for me.

Jon Orr: Interesting. You know, I think I, I, I feel the same experiences like math but it this like this, this class we did and you know, if you caught on quick with patterning really because it’s like patterning of examples, patterning of, you know, how the algebra worked, like if you, you could catch on quick, like you could be like, I can show up, I can do the work and I can move on, you know, and it’s it’s.

Thomas Nobili: What it was. And I just didn’t really it was just like, all right. Like it just didn’t really, you know, resonate. And like, obviously as a teacher now and working with teachers, we were all about the experience we want kids to have in math class. And we want kids to have that experience, to resonate with them and to build their self-efficacy and make them believe in their their ability to do math. And I mean, I didn’t really it was just kind of a very neutral, like you said, just kind of a neutral existence. Sure, sure.

Jon Orr: Where where where would you say that transition happened for you? Like, I know for me, it was like it was years in like ten years in where where I was getting frustrated and I knew I needed to kind of take a different approach. And I took a step in a different direction for a little bit. But like where where was that transition for you to be like, like, was it immediate getting into teaching where like, oh my gosh, like I have to completely, you know, give it, you know, the children and the students a different experience than what I had because, like, I didn’t do it that way. I kind of like, just emulated what I experienced for a long time. Or did you have a, like, where you like me? Where it’s like you realize something had to change. Tell me. Tell me about that kind of transition or or an introduction.

Thomas Nobili: Yeah, yeah. So no, it’s kind of similar to you. Right? I started out, in teaching. I taught, just like a small private school to begin with, and I just very much did kind of the way I was taught. Right. And a lot of the way I was trained, unfortunately, which is just very similar. Kind of I do you do we do stuff again, not really paying so close attention to whether kids necessarily had the conceptual understanding, just like if they were able to, you know, pass the test and that kind of thing.

And then, I moved, districts I started teaching sixth grade math in a and, it might be number two now, but at the time it was the largest urban district in Connecticut. So it’s a different population. And I started teaching and about a year or two and I kind of, think it was going okay, but I felt like I could see.

I could see that there was probably a need to kind of do things differently, especially, you know, having kids come in with the diversity of experience that they did. And so I ended up I don’t even remember how, but I ended up like reading about the Tim’s study. You know, that. And so I got really interested in like that.

And, so I watched all the videos and I started to read some of the work around it, and then that kind of led me to like this idea. Oh, they don’t teach math like this everywhere, actually. Right. So what what are they doing at that point was like in the in Japan, in China. But then, I just kind of kind of got hooked and I started reading other things, looking into other, research and, and I started just trying to I was like, you know what?

I’m going to just try this in my classroom and see what happens. And, and, and also kind of learn along the way. Right. Because like, I had to learn like, why does this work? Or, you know, like when we’re dividing fractions, you know, because like, I just knew at work I could do it, but sure. So I would just try stuff and I could kind of just gauge and see what was happening.

And like, I could see the kids were more into it. And I just kept kind of going. And I just became hooked at that point and just kept like, read everything I could find, you know, work with, colleagues and math coaches and started, you know, go to conferences and just try to learn. And then I would just try things.

I had a really supportive principal at the time, who was just like, really like, yeah, you try it. Anything you need for me, you know? So I didn’t feel like I, you know, it was like anything constraining me. And, that just kind of. Yeah, it just kind of took off from there. And, and then once, you know, I just started to see what that experience could be like and the response of students and I was hooked. So definitely probably about 4 or 5 years into my career.

Jon Orr: Right. So let’s, let’s chat about, instructional recipes. You know, this is the, you know, intriguing. You’re working with teachers, you’re supporting teachers, these days. But but talk to us about, like, what is an instructional recipe, Phyllis. Yeah, because I think that’s a relatively new phrase that I think a teacher wouldn’t have heard about. And your and your take on it.

Thomas Nobili: Yeah. So the way this came about previous to me, kind of doing some consulting, I was in, district as a central office, administrator. I was, director of, elementary math and science of another district here in Connecticut. And we were doing some work trying to bring about change using. And we were getting some training in this idea in the, methodology of improvement science, which is all very much about kind of small tests, changing, collecting data, trying to get better.

And so one of the things that they talk about in improvement science is this idea, and the term is not I wish they didn’t call. It is because when people hear the term, they they kind of like shut down a little bit because, but they and in the realm of improvement science, they call it standard work. Okay.

Yeah. People kind of get turned a little off about that. But basically this idea that if you’re in a system, any system, there’s probably a best way to do something, whatever that task is, there’s probably like a, like a and that way could evolve, right? If we think about like in a medical field or something, the best way to do a knee surgery now is not the best at what.

So it’s not it’s not, that it can’t change. But and so the idea is like we should probably, we should probably figure out a way to codify the best way that we know how to do something and help people to do it that way, so that, you have kind of, less variance in the system. And then when you’re talking about people, like, especially students like their experience from class to class is equitable.

So this idea was kind of interesting, and I, of course, was working with teachers. And one of the things that we had done a lot of work in, in the districts was this idea of having a common vision of what good instruction should look like specifically. Yeah. There’s again, also important, so again, for the same reasons in terms of, you know, providing equitable experience to kids.

But one of the questions I would always get is, Tom get it like these are the components of high quality instruction, right? We need to have kids, you know, working on rigorous tasks. We need to have feedback. But like, what does that look like? Like, okay, 2:00 in my third grade class, I’m doing this like and so that was obviously with my I had a team of great coaches.

And so I started thinking about this idea, as I said, and colleagues of mine as well, not just me, started to think about like, what would that look like in teaching, basically. So we settled on the recipe metaphor because for a couple reasons. So one of the things that we’re trying to shift, we tried to shift is it’s not about the individual teacher.

Like we don’t want to be judging the individual individual teacher. We really want to be just focusing on how do we refine the practice to be the best it can be. So when you think about a recipe. So the example I always use are teachers. Like if I ask you to try my blueberry muffin recipe and then tell me, you know what, you think, you might come back and say, oh, you know, it was good.

But like, I had to, you know, my oven, I had to use a different temperature because it’s a gas and not electric. And somebody else might say, well, you know, you might want to try it. Right. But, you know, something different here and there, whatever the case may be. And I know when you’re telling me that, that you’re not, you’re not saying that I’m a bad cook.

You’re just you’re just critiquing the recipe. And I think that was that has been a useful frame for teachers because so what we what we did, particularly in the math world, we said, all right, what are some of the high leverage practices that we know we want and we know that we know should be happening? So, for instance, things like launching the tasks, consolidating the learning, conferring, and we started to look at the research and we started to say, what what would that look like if we kind of codified some of the key points there and the, the idea of a recipe is, is not a script, right?

It’s not. Here’s a script that you’re going to follow. Because we know that teaching cannot be reduced to a script, but basically it gives folks kind of, some moves and some things to keep in mind as they’re teaching so that they don’t have to focus all their energy on thinking of all those things, and they can pay more attention to what kids thinking is and respond.

But it’s trying to balance, because we know that teaching is a very high cognitive load activity. I mean, there’s so much going on it taxes. So the idea is if we can if we can reduce some of that so that you can pay more attention to responding to students, let’s try it out. So we started to just kind of develop these recipes and kind of get teams of teachers together, kind of give them the spiel I just gave you about what a recipe is and how it came about.

Then say, Will you try this in your classroom and give us feedback about like, because we need to know, like in different contexts and different with different kids, will you let us know how it goes? And so people did and we started to get good feedback. In terms of how it, you know, it helped or working with a coach and and so we started to we would call them these recipe testing sessions and we would just work with teams of teachers and we, you know, we’d go through a recipe and then we’d make sure everyone kind of was like, okay, this is what we’re going to do.

Then we might look at a particular task or something that we were going to try with. We try it. People would kind of collect it from different types of data in terms of like how well, how will we know that this recipe is good, basically like Halloween. And then we’ve come back and talk about it. And then teachers would give us feedback, we’d make tweaks and we would try it and we oh, we didn’t think of that.

And it just started to, kind of become this process. And, you know, we were keeping different data points throughout the year, on different things, both process data points and outcome data points. But at the end of the year in in Connecticut, kids take obviously a state test and all that kind of stuff. And, you know, we saw some really good results there as well.

Like actually double digit increases in proficiency. So so we have this whole slew basically of, of recipes, which again are kind of like what’s the best known way of launching a task, for instance, or what’s the best known way of, consolidating the learning or how do we how should we answer kids questions? You know, we pulled from a lot of different things and a lot of them, use some of the Peter Bulletholes work in building thinking classrooms.

We’ve reference cafe fasteners, work. We have referenced, a couple other folks as well in terms of trying to bring that together for folks. And so that’s kind of the idea. And, you know, it’s been it’s been really as I said, it puts teachers in a position, I think that they are that they should be in, but they not have always been in where they’re the ones who are kind of okay, I’m doing research on my own practice and I’m giving you feedback.

So we’ve reverse the flow of feedback. Typically for us with teacher evaluation and things like that, someone like me would come in and say, I need you to, you’re going to do this, you’re going to do this recipe, and then I’m going to tell you how well you did it. And we basically flipped the script on that and said, Will you actually try this out in your classroom and tell us how it went and give us feedback, because you’re the one who’s actually implementing it, and you’re the one who’s actually has the expertise in the classroom.

And so we’ve kind of flipped that and and then we also interviewed kids. You know, the other thing we did to on this is, is after, teachers would start kind of shifting, right, using these as a ways to begin to just kind of shift the way they would do things. We talk to kids and say, so, you know, your teacher has been doing some things a little bit differently in math class.

Yeah. Tell us about that. And they had, you know, and we would we would share that with the teachers as well. And you know, the the kid, the student data was also really telling because, you know, they would they were really positive things to say about, you know, for instance, I like working in random groups because they, you know, I get to work with different friends or I like that the teacher doesn’t give help us too much.

And I have to think about it by myself. And, you know, I feel so smart and all these kinds of things. So it kind of reinforced, I think also for teachers that, you know, this is this is definitely useful. And again, the whole idea was just trying to support teachers to think about how can how can we make it, how can we kind of concretize some things so that it’s easier for folks to be able to like easier, but require less, less cognitive resource to pull that off in the classroom?

There’s so many things going on. So that you could focus more attention on kind of responding to student learning, instead of having to think through every little thing. And then, you know, over time, you know, as soon as teachers worked on them more, tried them more, you know, they made little tweaks and things that, you know, for their class, you know, just like you would expect.

Of course, like, well, they might, you know, I do it slightly different, because of this or that. And like I said, we also got, because the other thing is it’s the best known way of how to do something today, but that doesn’t mean that way tomorrow we got all kinds of feedback from teachers and different things of, oh, that’s a really good idea, which you write that in.

Because we never thought about that. And so we would, we would, we would tweak and and so it became this really, I think just, a different way of leveraging teacher teams in a school to kind of build, move toward a vision of what high quality mathematics instruction could look like. And instead of the focus being on trying to change the individual teacher, the focus was on leveraging the power of teams to work together.

And kind of research around practice and figure out how to make these things work, and then give us feedback so that we could ask other people to try and see what happened and that it became it became kind of that. And so that’s kind of where we’re at. And so we’ve got, you know, a slew of them that we’ve, we’ve developed and we and in my work now, obviously, I’m able to start to work with teachers in different districts and in, you know, different contexts and, kind of kind of bring this idea and say, you know, can we try this and, work with coaches to, you know, we, did a lot of work with coaches as well to, to to think about how as a coach, what’s your role in this process and think that so.

Jon Orr: What is a picture like? I what I’m imagining here is that, you know, and maybe, maybe this is where the clarifying, you know, comes from is that you’re saying we’ve looked at different approaches, we’ve looked at, you know, different techniques and strategies. To do say different things in the classrooms. And now I’m trying we’re trying to provide, say that guidance to teachers.

So what is the what does it, let’s say look like. Is it a are you say providing teachers say a lesson plan that says this is for this particular grade and this particular level? Or is it like here is here’s like a collection of, of tools that you can put in your tool belt. And then it’s, it’s not specific to that particular grade or that particular concept, but we can help you implement it in that. So like tell us like what does this look like in a teacher’s hands.

Thomas Nobili: Yeah that’s a great question. Yeah. So it’s much more like the latter. So not less than specific. Not so it might be. So I’ll just use a launching the task one. Right. So we have this idea what do we want to launch a task. So we know some things that we you know and a lot of this you know, paint a little dots work.

We want to get kids moving within five, you know, within five minutes of starting a class. Right. So and we want to have kids, you know, and then standing or we want to, you know, do do that. And we want to make sure that when we launch the task, you know, we don’t we don’t over teach into it.

Right? We don’t lower the cognitive man to the task before kids have a chance to to do it. So, so, so that the, the, the recipe is much more just like, hey, here’s some things you want to keep in mind. Pay attention to when you’re launching the task. Whatever task it is. Now, what we might do is if we’re working, let’s say I was working with a group of fourth grade teachers and we were going to try this recipe out.

We might say, well, let’s all look at a similar task to try it with because we might want to, like, develop the launch script together. We may want to like and say, well, what happens if we send kids off and they don’t know what to think about that? Like what? What might we do there? So we may apply it to a specific.

But the recipes themselves are just about what we consider high leverage instructional practices, not like not a lesson plan. Right? Okay. So they can be applied throughout, you know, whatever curriculum you’re using, whatever task you’re using. The other thing we tried to do with them too, is really so a lot of our the work that I’m doing now with colleagues and at the time was looking at this idea, in terms of instructional equity.

So, you know, there’s certainly equity is a major, issue and a major conversation in the, in the educational landscape today. But we found in our work with teachers and schools that a lot of times, instruction and equity were not seen as the same. They weren’t seen as merged, you know, there was. And so we started to talk about, you know, a lot kids spend most of their times in classes.

Yeah. There is certainly, variance in the quality of instruction, unfortunately, that different kids receive. And, and sometimes, you know, kids who are more marginalized tend not to receive as, quality of instruction as others, unfortunately. So what we also try to do with these practices was kind of flesh out and say, well, certain practices are more equitable than others because they’re less susceptible to teacher biases.

So for example, random grouping. Right. I can’t if I’m not in charge, making the group even my own, you know, any biases that I might have unconscious whatever don’t can’t prohibit because the group is random. Right. So for example, so we also tried to pick practices that were less susceptible to that and more kind of more equitable to, to to start putting into practice as well, in these recipes so that and the other piece too, right, we would, we would, we would get from teachers sometimes.

Right. Always out of, out of a good place, but. Oh, I’m not I’m not sure that I can do this because, like, you know, I have you know, I have I have a high population of of kids with, IEPs or special education students right now. And we would always just pick well, let’s just try it. Let’s just see what happens.

You’re giving us feedback, right? We just want to know, like and so in certain situations where in a classroom kid, all the kids might not have had that experience because there might have been separate kind of like, okay, this group’s going to do this, and this group’s going to do this. Only involved in these recipe testing sessions. We kind of we said, well, let’s just do it all the students and see what happens.

And, that was really powerful too, because many, many times, kids were doing things that teachers didn’t think they could do. And so that set us up to then say, oh, well, let’s try that again, see what happens. Right. So those are definitely kind of an equity piece to it as well, in terms of trying to, make the experiences that kids are having in classrooms as equitable as possible, as high leverage as possible, so that, you know, it really wasn’t to, you know, again, right.

The ultimate goal is like, we don’t want the quality of your education to be dependent on which teacher you get right. If we can all be using some common practices that we know the research supports are high leverage, are maybe more equitable, are going to, you know, really, put the learner in the forefront. Can we try to figure out how to make those work together? Because I think too is I think it’s really hard as an individual teacher to try and just like, figure all this out as if you’re.

Jon Orr: Well, it’s every everyone’s going back to the drawing board, right? So it’s like unless you’ve had training specific training on, on these ideas, you’re kind of guessing at what is the best practice today. You know, what is what should I be doing if I’m trying to engage my students this way? Like like I’m, I’m, I’m on your your site right now and I’m looking at, say, the recipe for hints and extensions.

Like I think people it’s like, how do I give a hint. Like like like maybe I’ll just give a hint that am I doing the hints the right way? Like, like that’s a common, common, common question that we have. And then I think I like I like that it is it is general enough that say, this is these are the things that happen in our classrooms on a regular basis.

And then what could I do if I’m looking for guidance in that area? And you’re giving those suggestions. So like, I guess if we go down the rabbit hole for a snack about hints and extensions, like, like walk us through, like what does that look like? Like knowing that, say, the listener right now can’t see what I see on the screen.

Thomas Nobili: Yeah. So, generally what we’ll do with a recipe is we have a little description of like what the practice is and why it’s high leverage at the top. And then we kind of have the process. So usually there’s pre-work but built out into okay, here’s pre-work and then here’s the actual process. And then here’s maybe some additional considerations.

So with like hints and extensions, the pre-work is obviously like you want to know the tasks that you’re going to be, doing with the children. Well yeah. On a start to anticipate where what types of hints students might need and what types. And obviously have your, you know, what, how you’re going to extend it. Because thinking of that, obviously you can’t always anticipate all of that.

But trying to think of that all in the moment is really hard. Back to that cognitive load piece. And the thing we say about pre work, especially whether it’s an extension or anything else, is you’re thinking about what and where, like what types of hints and extensions might give and where in the lesson might give them. But you’re not deciding who, right.

You’re not deciding who until you actually have evidence of who needs them. Right. Sometimes. And I know even like back when I was, you know, getting training and stuff, you know, we would we would often make decisions about what students could do before we even gave them a chance to. Sure. Okay. Oh, well, I’m going to have these things ready for Johnny because, you know, Johnny always struggles.

And so we always tell teachers we’re not telling you not to have the what in the where. But let’s not decide on the who until we actually give them a chance to do it. And then in the moment, as Julie, you know, Julie Dixon uses the terms just in case, just in time that we’ve used that language for teachers.

I think they grab they grab on to like, let’s not give them the hint just in case they need it. Let’s give it to them just and it just in time moments. So we go to the pre-work and then you know, it talks about the process. And then so there’ll be kind of different steps to think about, different hints to think about.

And or different practices to think about when giving hints and extensions. So we’ll talk about. Sure. You know, if you notice, a group is, you know, having having a hard time or at a stuck point here’s, here’s how you might approach them. Here’s here’s what you might do. You might give the talks about, in Peter Little’s book, he talks about the two different types of hints, right?

Hints to increase ability, security, decrease challenge. He talks about what those are and why you might give them. But then, you know, give little like I’m personally in that recipe as well. I’ll say, look, if you find yourself always having to give a hand to decrease challenge because kids are at a, at a kind of a frustration point and you’re like, I really got to bring I got to bring this down really quick or I’m going to lose them.

That’s an indication that your timing’s off, right? Because if you’re always here, you’re late. Basically, you’re getting there too late. So you might want to think about, how you can write because you really, obviously want to be giving hints to increase ability. They take longer. And so and so then, you know, there’s some suggestions it gives on there for, you know, well, so maybe you know, because a lot of things that teach it’s time to and it is the teachers are trying to give like they’ll try to they’ll try to go to each group right.

And give him. And so but they don’t always think about how to leverage the groups a group they just met with to, to, to help another group. Right. So they’re trying to actually be the one that, kind of intervenes. And sometimes you can buy yourself some time so that you can get that timing right to be like, you know what?

Can you why don’t you go talk to, you know, group number three? Because they just had a really similar question. We talked about it, you know, and so leveraging that knowledge mobility. So just tips like that like finding yourself late. Are you leveraging. Are you trying to do everything yourself or are you actually leveraging the knowledge in the room.

Right. Well to so that you don’t have to, because if you’re trying to do it all yourself, likely you’re you’re never going to be able to get time. Yeah. So just like things like that. So again, not scripts but just like here’s things to think about. If you find this out and you might want to try this, you know, if you know that kind of thing and then, you know, talks about extensions and it talks about the different types of extensions.

Sure. You know, particularly in that in that framework and talks about what, you know, when you might, you know, when you might want to give. Right, though maybe to extend, you know, if it’s a thin slicing task, this type of extension is probably more useful. If it’s more of an open ended task than you’re going to want to probably use one of these types of extensions.

So. Right. So things like that. And again, just so that you kind of have that those guardrails going in again, we can’t script out everything that’s going to happen because that’s a classroom is, is is a dynamic chaotic system. And there’s no way that you know you can’t you can’t predict. Right. But we’re just trying to make it easier for teachers to be able to right. Make those decisions. Make that takes some of them off their plate.

Jon Orr: Yeah. Makes sense. Makes sense. Now what I’m looking at at these, recipes. You know you’ve got to think pair share recipe. You got it. Like what do you do with cold calling on students consolidating the lesson. You know, how to answer questions, from students. So when you think about all of the, say, recipes you’ve been building and putting together and you think about, you know, you talked about pre-work.

So thinking about like, what does it like if a teacher, if a teacher is going to be flexible in the moment to utilize, say, these recipes, if the teacher is going to, you know, put these into action. If you think about all the recipes you’ve been building, like, is there any comment like common things teachers need say to get, you know, to be strong at or to think about before they engage in and say, utilizing some of these recipes, what would you say is like if you could pick one thing, like, what’s one thing?

They’d be like, A teacher should be strong here before they can say, engage in a lot of these best practices in the classroom.

Thomas Nobili: Well, obviously, I mean, from a management perspective, I mean, if you have a teacher that is still maybe a newer teacher or something, that’s still like trying to just get like their management and transition routines down, I would, would probably, you know, suggest that, you know, they do that first before you, before you, you know, try to do so.

Although some of these have some of that built in. But if you’re trying to, if you’re trying to deal with, with kind of thinking in a classroom, you know, you’re trying to deal with, okay, managing what’s going on with students and making sure and getting your routines underway, and you’re trying to do things at an instructional level.

I mean, that’s really hard to do. So I would say, you know, if it’s a newer teacher or something like that, we might want to make sure, okay, we just we feel comfortable just like kind of with the class. Sure. Kind of, a community that that feels good. But really beyond that, and in the recipes, I think, you know, just like any instructional practice, some of them are easier to implement and some of them are harder.

Right? So like something like, I think pair share is, is that’s why we start with a lot because it’s not that sure. Most teachers are doing some version of that anyway. Right. So the other thing, you know, I should mention when we talk to teachers, okay, so just to be clear, like we’re not we’re not like let’s say we’re looking at the think pair share recipe.

We’re not saying that you don’t do a good job, but think pair share, right. Like again, I say to teachers, I don’t know, you may be doing everything on here. You’re probably doing at least some things on here. Right. So let’s just say like again this is just about we’re trying to figure out how to codify what we’re all doing so that kids can get a equitable experience.

So anyway, something like think, just think pair share. You know, I mean, it’s it’s not it wouldn’t take that long for a teacher to even if they were unfamiliar with it. And again, most teachers do some type of try to talk to peer share to begin with. So it’s not like they’re starting from scratch. It wouldn’t take that long for you to be pretty proficient and comfortable with that.

For that to be basically become routine, or you didn’t have to devote a lot of your cognitive resources to it because you’re like, okay, here’s how we’re going to do it. Something like consolidation is much harder, right? Because there’s a lot more. You have to know more about the math. You have to manage student discourse. You have to manage engagement.

So we probably wouldn’t start with that for most teachers, because the other thing, too, is right. I mean, we want we want teachers to be successful. So we want to start in a place that feels like they can be successful with it. Because what we found is and, you know, depending on the teacher might have started, you know, if you have a teacher that’s really doing a lot of this stuff and they just want to kind of move to the next piece, you know, we definitely can we don’t want to waste their time either.

But something like think pair share, we use the tasks launch one a lot because also, you know, the thinking too is like if you’re not if you’re not launching the task as effectively, that’s going to maybe affect everything else that goes on. So maybe let’s kind of like get to the sauce, right, and say, like, if we’re over scaffolding to launch the task where it’s taking us 25 minutes to get kids working, then let’s fix that.

Before we talk about extensions or consolidation. But yeah. And so what happens is teachers, you know, they they do it and it’s not it doesn’t mean that, you know, the other thing we, we, we try to frame for teachers is it’s not about good or bad. Did it go good. Did it go bad. Because that’s really the wrong question to be asking.

We just want to know what we’re learning. So when we debrief right when we come back maybe folks have tried out a recipe for a week or two and they’ve, they’ve kind of tried it out on their class, maybe with the support of the coach, maybe not. Depending on what they want. We come back and we say like all right, let’s talk about this.

It’s never it’s never, you know, around a good or bad thing. It’s what did you learn? What are some things that we might need to, you know, tweak. Are were there any stumbling blocks that you encountered that we didn’t think about? And that is a really interesting one, because teachers will say they’ll come up with things.

And then what generally happens is some other teachers like, oh, I that happened to me and here’s what I did. And then you kind of get this almost knowledge mobility among teachers. And then people say, oh really? And then we’ll say, well, okay, do you want to run it next week and try that and see if that works for you?

And they’d be like, yeah, let’s do that, you know, and then you and then I’d be, I’d find myself right, going to different schools and then I maybe I’d meet with a different, a different group of teachers in a different school. And somebody would bring up the same thing like, well, I tried, you know, I tried to think peer share and, and, this is a stumbling block.

And if somebody didn’t have, you know, one of the teachers at the table didn’t have, didn’t experience or that it didn’t have a I’d be like, oh, well, I was just over at this school. And you know what they said, they tried. And so I was kind of like. And so that was kind of cool too. And so I think, yeah, there’s really there’s really no barrier to entry.

Right? It’s I mean, you want to just figure out like where what what’s going to make most sense to where the teacher is, what’s going to feel to them. Like, okay, I can do this. And the thing about the recipe is to reframe is you’re doing all these things anyway. So it’s not one more thing like you’re going to launch a math task, whether whether you do it this way or not.

So I’m not asking you to do anything beyond because we all know that teachers have absolutely no time for that. I’m just asking you to do the same thing you do, maybe in a slightly different way. And so I think that like resonated with teachers as well because all right, well I’m going to do this anyway. So all right, I’ll try this five minute launch and let you know how it goes.

Right? Right. Because all I’m asking you to do is commit to that or I’ll do this thing. Pair share routine during my talk for ten minutes and tell you how it goes. And then we try to we try to build right. And just engaging with the teacher. What feels good for you feels right for you. Yeah. Let us know. Right. Tell us. And then we would try to recite baby steps.

Jon Orr: Baby steps go a long way right. So so good good, good tips there for sure. Tom, it’s been great. Great chatting you with both instructional recipes. Where can where can folks go if they want to learn a little bit more? Where can they go to can maybe contact you or what? What kind of takeaway do you want to leave these folks?

Thomas Nobili: Well, definitely. I have a website, for my, consulting. Which we can, I’m sure. Link. TJ Core Consulting. It has, all the recipes that we have are available. They’re free for people to, to try out. Also my contact information and some other resources because, again, anyone who wants to talk further has questions.

You know, I would sure. I also, write, publish a Substack as well, called the core of the matter. Which, is mainly it’s about an instruction, a lot about math instruction, sometimes not, but, people can check that out as well. So those are two places I would say.

Jon Orr: Awesome. We’ll, we’ll link those up in the show notes. So if, folks are listening and they want to kind of have a peek at, what the instructional recipes have look like or see what see what the variety that are there. Get on over there. You can click a link in the show notes. But Tom, thanks. Thanks for joining us here.

Thomas Nobili: Thanks, John. Appreciate it.

Jon Orr: Awesome stuff. Have a great day.

Thanks For Listening

- Book a Math Mentoring Moment

- Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

- Leave a note in the comment section below.

- Share this show on Twitter, or Facebook.

To help out the show:

- Leave an honest review on iTunes. Your ratings and reviews really help and we read each one.

- Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, and Spotify.

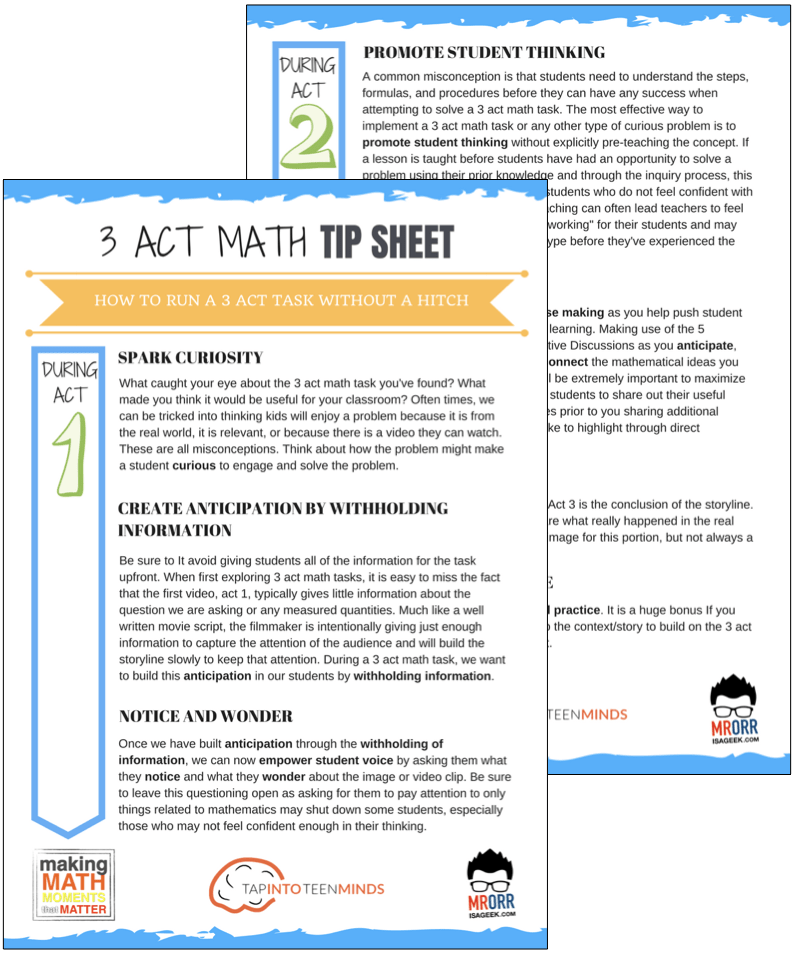

DOWNLOAD THE 3 ACT MATH TASK TIP SHEET SO THEY RUN WITHOUT A HITCH!

Download the 2-page printable 3 Act Math Tip Sheet to ensure that you have the best start to your journey using 3 Act math Tasks to spark curiosity and fuel sense making in your math classroom!

LESSONS TO MAKE MATH MOMENTS

Each lesson consists of:

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson consists of a Teacher Guide to lead you step-by-step through the planning process to ensure your lesson runs without a hitch!

Each Teacher Guide consists of:

- Intentionality of the lesson;

- A step-by-step walk through of each phase of the lesson;

- Visuals, animations, and videos unpacking big ideas, strategies, and models we intend to emerge during the lesson;

- Sample student approaches to assist in anticipating what your students might do;

- Resources and downloads including Keynote, Powerpoint, Media Files, and Teacher Guide printable PDF; and,

- Much more!

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson begins with a story, visual, video, or other method to Spark Curiosity through context.

Students will often Notice and Wonder before making an estimate to draw them in and invest in the problem.

After student voice has been heard and acknowledged, we will set students off on a Productive Struggle via a prompt related to the Spark context.

These prompts are given each lesson with the following conditions:

- No calculators are to be used; and,

- Students are to focus on how they can convince their math community that their solution is valid.

Students are left to engage in a productive struggle as the facilitator circulates to observe and engage in conversation as a means of assessing formatively.

The facilitator is instructed through the Teacher Guide on what specific strategies and models could be used to make connections and consolidate the learning from the lesson.

Often times, animations and walk through videos are provided in the Teacher Guide to assist with planning and delivering the consolidation.

A review image, video, or animation is provided as a conclusion to the task from the lesson.

While this might feel like a natural ending to the context students have been exploring, it is just the beginning as we look to leverage this context via extensions and additional lessons to dig deeper.

At the end of each lesson, consolidation prompts and/or extensions are crafted for students to purposefully practice and demonstrate their current understanding.

Facilitators are encouraged to collect these consolidation prompts as a means to engage in the assessment process and inform next moves for instruction.

In multi-day units of study, Math Talks are crafted to help build on the thinking from the previous day and build towards the next step in the developmental progression of the concept(s) we are exploring.

Each Math Talk is constructed as a string of related problems that build with intentionality to emerge specific big ideas, strategies, and mathematical models.

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Use our OPEN ACCESS multi-day problem based units!

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Partitive Division Resulting in a Fraction

Equivalence and Algebraic Substitution

Represent Categorical Data & Explore Mean

Downloadable resources including blackline masters, handouts, printable Tips Sheets, slide shows, and media files do require a Make Math Moments Academy Membership.

ONLINE WORKSHOP REGISTRATION

Pedagogically aligned for teachers of K through Grade 12 with content specific examples from Grades 3 through Grade 10.

In our self-paced, 12-week Online Workshop, you'll learn how to craft new and transform your current lessons to Spark Curiosity, Fuel Sense Making, and Ignite Your Teacher Moves to promote resilient problem solvers.

0 Comments