Episode #358: How Useful Are Pacing Guides in Math Instruction? Balancing Alignment and Autonomy.

LISTEN NOW HERE…

WATCH NOW…

Can schools create consistency in math instruction while still allowing teachers the freedom to meet the unique needs of their students? In this episode, we dive into the tension between alignment and autonomy in math instruction, exploring how pacing guides and common assessments can support equitable, ambitious math teaching—without becoming restrictive.

Join us as we unpack what “too much” and “too little” direction looks like and discuss practical ways to establish a strong foundation while honoring teacher expertise and student diversity.

Key Takeaways for Listeners:

- How shared expectations and structures can support equity and improve student outcomes.

- Signs that pacing guides and assessments have become too rigid—and how to course-correct.

- Strategies to give educators flexibility while maintaining a common instructional vision.

- Practical approaches to ensure consistency without stifling responsive teaching.

- How alignment can work for differentiation rather than against it.

Attention District Math Leaders:

Not sure what matters most when designing math improvement plans? Take this assessment and get a free customized report: https://makemathmoments.com/grow/

Ready to design your math improvement plan with guidance, support and using structure? Learn how to follow our 4 stage process. https://growyourmathprogram.com

Looking to supplement your curriculum with problem based lessons and units? Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons & Units

Be Our Next Podcast Guest!

Join as an Interview Guest or on a Mentoring Moment Call

Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

Book a Mentoring Moment Coaching Call

Are You an Official Math Moment Maker?

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Kyle Pearce: Hey, hey there, Math Moment Makers. You are here with another episode with both Yvette and I, and we’re gonna be riffing today on an idea that was inspired by a book that we’ve all been digging into lately. This is a book John picked up, one of his favorite authors, Dan Heath, and it’s called Reset. And in this book, and the subtitle of this book is Change What’s Not Working. So today,

As you can imagine in education, there’s lots of things that are working. You know, we do a lot of great work each and every day. We show up, we give our best, we try our best, but we also know that there’s things that aren’t necessarily working, right? And we’re constantly trying to figure out how or what can we do in order to do things better. And when we’re working with district leaders through our district improvement program,

You know, there’s a couple ideas that are constantly coming up and they’re constantly at play. And it’s something that is really hard to get a finger on. And the two ideas are alignment. So staying aligned in our schools and our district so that everybody has a clear vision. Everybody’s on the same page that we’re not just all over the map. But then oftentimes when we go hard on alignment, what ends up happening is

autonomy goes down, right? And people stop losing that autonomy. And that oftentimes means that they’ve sort of lost the, you know, sort of the the the will to sort of put that extra effort in because it’s not necessarily their idea. And this can be very difficult. And really, what we want to do today is we want to unpack how we might be able to get the best of both worlds here, because we do want alignment, I think.

all of us want alignment. We all want to be on a same page and heading in the same direction. But we all want to feel like we have some control, right? That the decisions we make aren’t just mandated to us and that we’re blindly following this idea or that idea. So how do we bring these two things together? And how do we make sure that we sort of strike a nice balance with both of these ideas?

Yvette Lehman: in the chapter on autonomy and alignment from this book, they talk about this idea that sometimes we see autonomy and alignment living at the end of a spectrum with alignment at one end and autonomy at the other, but in reality what they describe is that autonomy and alignment are a matrix and so you know imagine a scenario where you could have low autonomy, low alignment or high autonomy, high alignment and what the idea is is that these two ideas do not contradict one another. Like it’s possible to live in a space where alignment is high and autonomy is high.

Kyle Pearce: Interesting. I want to really paint a picture here because I think in a lot of, you know, I always talk about how we think digitally, right? We think on or off. We think, you know, all in, all out. And that’s very easy for us to follow. But you’re talking like when you say a matrix, it’s almost like a two dimensional world, right? And as a math geek, you know, one of the resident math geeks here, I’m picturing like an X and Y axis, right? From zero to, you know, 10 or 100.

and then a y-axis from zero to 100. I don’t think we’re gonna go into negative territory here because I’m not sure how we quantify that. I’m sure someone could argue that. But we’re looking at essentially the comparison as to like, okay, if zero represents like no autonomy, no alignment, that’s like having like a point on the origin of this graph. And if we go all in on say alignment,

right and let’s pretend alignment is our X axis it’s sort of like okay we got all alignment but we’re still have no autonomy and you know what we’re going to dig into here is sort of like what typically happens when the dot on this graph sort of moves around or the dot in this matrix sort of moves around from like neither of both all in on one all in on the other or way out there you know and and almost like picturing like this nice

linear graph going diagonally all the way up to that top right corner that sort of suggests that you actually have both. actually have alignment and you have autonomy. And you know, what does that look like and sound like? So start us off here, Yvette. Let’s talk about the area where you kind of have neither, which I think everyone would agree we don’t want neither of these two things. So tell us what typically happens here.

Yvette Lehman: Okay. Well, I mean, I think when we, let’s describe neither. You know, I’m not even sure how I would define that in education. So in that scenario, we have no alignment, which means from class to class, school to school, there is no consistency. But somehow we’re still micromanaging people. Right, right. Yeah, right.

Kyle Pearce: Hmm. Right to do what right because it’s like you’re not you’re not aligned like we’re not on the same page here but I’m gonna make you do these things anyway and I wonder if it’s like one maybe principal is managing for their own agenda and then another principles maybe managing for their own agenda so it’s like every building every classrooms kind of doing its own thing but nobody actually feels like they have any freedom when in reality it’s almost like you you’re all doing something different so Isn’t that freedom? I’m not sure. Like that seems very difficult to achieve for sure.

Yvette Lehman: I could also see it where it’s like we’re micromanaging logistical things or we’re imposing, know, everyone shall do blank, but the things that we’re imposing have no real impact on student achievement or effective teaching practice. So there’s like, sure.

Kyle Pearce: I’m picturing behavioral things, almost like we’re going to have desks have to be in a row, classrooms have to have a certain volume. Usually that means the lower the better, right? Because classroom management is important, and people got to be on time. We’re not letting kids out of class early. Those types of things that are very logistics related, but not necessarily not necessarily contributing to student achievement. We have no clue whether that’s helping or hurting in terms of achievement.

Yvette Lehman: Right. Yeah, so that would be kind of our worst case scenario, I think, where it’s like, not only are we not aligned on anything, but we also are micromanaging. know, teachers might become very indifferent because they feel they have no voice, no power, no say in any of the decisions that are being made. There’s just a lot of things being handed down to them without transparency around why or the impact.

Kyle Pearce: Interesting, interesting. So I’m going to guess here. And I think for most people listening, I don’t want to spend too much time there because I feel like most people are probably like, we’re more this than that. Meaning we have one of these two things maybe, but maybe haven’t found that balance. So you’re probably not in this place we just described. So now I want to take the dot, and I want to go along the x-axis. We’re going to go all the way to the right, and we’re going to talk about having high alignment.

but low autonomy. before we talk about that, I just want to say, feel like when it’s almost a bit of an oxymoron though, to me, to be honest, because it’s like, if I have high alignment, know, usually true alignment means people are like behind it, you know, like people feel good about it. And I’m going to argue that if we had true alignment, but people felt they didn’t have autonomy,

I feel like that alignment would almost be sort of like an act, like a bit of a show. Like you’re kind of like, I’m gonna do this because I still have to. I’m still being micromanaged. The district or my principal or whoever supervising me has a vision of what they want and they’re imposing this on me so that I am aligned, even though it’s like I’m doubting that what…

is being done is that it’s like at its best effort or maybe in a positive or constructive manner. What does the book say about when we have high alignment and low autonomy?

Yvette Lehman: Well, I’m actually going to give an example of a call that I had recently to describe a scenario that matches exactly this. So I met with a t-shirt recently and you know, we all, often ask, know, what’s your pebble, what’s a challenge. And this teacher described that they work in a really high achieving district and there is a ton of pressure around pacing. And it’s like everybody shall teach these lessons in this order, at this time, for this number of days. You can’t fall off the pace. And the reason for that, and I understand the reason, is that they want students to have a very similar learning experience, whether they’re in class A or class B, school A or school B. So no matter where you travel within the district, everybody is learning this concept at this time, for this length of time, using this resource.

Kyle Pearce: makes a ton of sense, right? Like from that logic, from that logic. But it doesn’t necessarily equate to constructive or productive things taking place, it sounds like.

Yvette Lehman: Sure. For sure. Yes.Right, so what the teacher was sharing is that, you know, this teacher has invested significantly in their own learning around mathematics. They have deep conceptual understanding and they were feeling very handcuffed when it’s like they knew their students needed more time on this concept compared to another concept and their diagnostic suggested that they should spend more time here versus there or they really felt that the lesson and the resource

didn’t give them the opportunity to approach it conceptually and they wanted to tweak the lesson to ensure that they weren’t just going straight to the procedure. They wanted to do some front loading through concrete to build understanding. And the teacher really felt like they did not have the freedom to do that.

Kyle Pearce: Hmm. So in a way, it’s like what I’m hearing and this, this kind of helps to, to highlight what I was getting at in terms of this alignment when there’s high alignment, it sounds like this teacher isn’t necessarily disagreeing with the overarching concept of trying to keep buildings on the same pace. And, know, one of the things we saw when we were at our district, their event was, you know, we were always concerned about a student who is maybe a transient.

Right? And all the statistics, and not just in our district, but elsewhere as well, like students that maybe bounce around from school to school because maybe they’re moving quite a bit. Maybe they’re renting, and now they’re picking up and moving to a different part of the district or the city or wherever they might be going. They land in another grade five classroom, and because there’s no pacing, then that student might have actually been already

received that content earlier in the year, or it might actually be the opposite. They get something else new, but then they completely miss something else because of how the pacing was, you know, not aligned here. So it sounds like this teacher you’re talking about is not necessarily against this idea, but now they’re feeling as though they don’t have any, or they have very low autonomy in order to do what they feel is the right move. And I’m gonna argue as well, like here’s one of the challenges when we want alignment.

and we want certain things to happen, and we have good reason for why we’re going to do those things, but then we forget to look at the things that we now miss out on. Because I have a funny feeling that her class is made up of a group of students that might be different than the next class. And I also bet that the district is probably pushing for differentiation and pushing for meeting students where they are and giving students the best next step and

all of these other things, but then we have this other structure put in place that is for good reason, but it sort of is counterproductive to this other goal or this other, you know, objective that we might have in the district.

Yvette Lehman: Now let’s talk about where we have the other, let’s say, extreme, where there’s high autonomy across the district and low alignment. Let’s describe a scenario that would be reflected by that point on our graph.

Kyle Pearce: So here we have high autonomy and I’m trying to envision like what this might look like and sound like. Like I think a lot of people here’s the here I was about to say I think a lot of educators would like high autonomy. I’m gonna guess that a lot of the listeners of this podcast would like the idea of high autonomy but not everybody likes high autonomy and I think the less confident you are with say the content or

what the right move is, the more uncomfortable you might become with having that autonomy, right? Because there’s a lot of responsibility that goes with having more and more autonomy, means more and more decision making that falls on your plate. And that could also be a challenge as well. So we have a lot of autonomy here, and I’m wondering if we’re kind of uncovering a little bit of some of the challenge here. So I have a lot of autonomy, not a ton of alignment. And I’m envisioning that like,

This is the example that we share with our district leaders. Usually early in our district improvement program, we use the analogy of puzzle pieces, right? And we have a picture of all these puzzle pieces all over the table. And they’re all great teaching practices. And every teacher has the best intention in trying to push that puzzle piece around. But the problem is all these pieces are kind of moving around, but nobody really knows what that finished puzzle is going to look like.

where they should be pushing that puzzle piece too. So I’ve got autonomy. So I’m all in on this one idea over here and I’m doing a great job with that thing. But then we go to the next classroom and that teacher has autonomy as well. Maybe they don’t have as much content knowledge understanding. And what they think is the right move is to do a lot of rote and a lot of memorization and not a lot of work through conceptual understanding simply because maybe they don’t have it themselves. So I’m imagining this world where

You know, while you have a lot of educators maybe doing their best and working really hard, I picture maybe the end result when you don’t see any traction happening from year to year. I can imagine that that could almost cause more burnout than necessary because I know how it feels when you work really hard on an idea and you push it and you push it and you push it, but then you don’t feel like you got the results that you were after. It can oftentimes.

lead to burnout if you you just keep feel like you’re spinning your wheels and it’s like you’re in a you’re in a Jeep over here stuck in the mud and the next teachers over here in a in a different Jeep stuck in the mud and we’re just spinning our tires muds flying everywhere and I think the word that they use in the book is it feels pretty chaotic in terms of the experience going on there.

Yvette Lehman: think that you made a really good point that when you have high autonomy, so a year ago, if you had asked me, I would have advocated for high autonomy. And I actually think I have drastically changed my position. We say this all the time, right? Strong convictions loosely held. know, a year ago, I was so, I guess, I believe so strongly in responsive instruction. And I believe very strongly that…

no two classes could run the same because you have such diversity and learner profile and entry point and all of those things. But now that I’ve come to realize that my understanding of equity was really about, you know, making sure that every single student received the responsive instruction that they needed to get to the end of the year successfully and hit those grade level expectations or standards. But that requires a very knowledgeable, very strong facilitator.

with strong content knowledge. And the problem is when you don’t have alignment, what’s happening in class A can be so drastically different from what’s happening in class B. So is that an equitable learning experience for those students? So if I’m a grade five student at this school, and this is what the rigor is, this is what the expectation is, this is how learning looks, and it’s drastically different from school B.

Are we creating an equitable learning opportunity for all students across the district? Do we all have a common understanding of the rigor that’s expected at that grade level to ensure that students are successful moving forward?

Kyle Pearce: That’s it’s so interesting too, because like I picture it’s so vastly different that if there isn’t any alignment, right? Because we’re talking low alignment, high autonomy. I’m sure there’s never a time where there’s zero alignment and 100 % autonomy. We’re just talking generally high autonomy, low alignment. And it’s almost like I picture it’s like you’re just gambling.

in a way, like as a school, as a system, we’re gambling because we’re just hopeful that it’ll all work out. And I will say there’s some good reason why you might go that route. And it’s because you know that educators have good intentions, right? Everybody has good intentions. You know that they’re doing the best they can do for students. But at some point, we also need to create and one of our former

former supervisors used to always talk about, know, like, let’s, let’s let people play in the sandbox, but we got it, like, at least give them the sandbox to play in, meaning like, we’ve got to give them something so that there are some boundaries there, you know, and it doesn’t have to feel like it’s, you know, it’s holding you back or you’re handcuffed completely. But we do need to make sure that certain things are taking place so that there is that equity taking place. And then

opportunities for autonomy to sort of fit in. I think this is a nice segue for us to kind of talk about, you know, sort of the ideal situation. Like this is sort of the, you know, the bullseye. If we could ever get to a place with high alignment and high autonomy, what typically do you envision we see in different classrooms across our school or our system?

Yvette Lehman: Well, maybe we could talk about maybe some strategies that some boards are implementing to try to create this. And so one of the strategies that again, I would never have considered a year ago is putting in place common summative assessments across the grade level. a formative assessment, of course, is going to be ongoing responsive. But when it comes to

capturing achievement of the grade level standards or expectations can we have common assessments? And the reason I’m now ready to advocate for this move is that by having a common summative assessment, we all know what the level of rigor is. We have a common understanding of by the end of this learning cycle, this is what a grade five student needs to demonstrate to meet the standard, to meet the provincial standard, to meet the state standard.

And so the problem is when we’re not consistent and your summative assessment is all knowledge questions with no high cognitively demanding questions and your kids get perfect, where I’m giving a summative assessment that has a range of questions from knowledge to thinking and application, it’s not the same. Like we’re no longer having the same expectations of the students at the fifth grade level.

Kyle Pearce: Right. It’s so that is so interesting. I think it’s I picture there’s some people out there that might be doing a little bit of squirming and they’re like, know, and now here’s the nuance, though, is that if we did this in a high alignment, low autonomy environment, I think that this could lead to possibly some negative consequences, right? Where you get people kind of pushing back or now it’s like, I’m just going to teach to this test. This is all that, you know, all that they want me to do anyway.

Right, like these are some of the feelings that I might get if I’m feeling handcuffed. But if I’m in a high alignment, high autonomy situation where we go, okay, well, what’s the purpose of doing something like this? And the purpose is so that we’re all on a similar page, we’re all on a similar playing field because this is one of the areas that because we’re humans, you will not accidentally.

get to the same level of rigor, the same level of thinking or the same, just the same general assessment or evaluation, even if you want to call it that again, we’re going to still use it formatively, but it’s really to give us some information as to where we are and where we could go better or where we could get better because here’s the nuance. So we know that in certain schools or certain classrooms, right?

If a group of students have typically or maybe historically performed poorly in that building, we know that the rigor being taught in the classroom often falls to sort of meet the standard that’s sort of been set there, right? Now it doesn’t solve the problem of helping students to get to this standard that we want to get them to, but it allows us to not at least pull the wool over our eyes to think that

Hey, the class average is blank and we’re on track and we’re doing all the right things because the reality is is that we’ve sort of set the bar at wherever it’s been set at and a different school has set the bar in a different place.

Yvette Lehman: What I would love to see happen in my ideal scenario is that we have a lot more, let’s say alignment at the tier one level, because we want to ensure that all students have access to grade level content on grade level. Like we can’t be bringing the rigor down or cutting out half the expectations to teach the middle. Because what happens when we do that is we actually create learning gaps for

all students, even students who wouldn’t have had them otherwise, that’s the result of instruction, not of, you know, high absenteeism or, you know, a learning disability or trauma, like whatever it happens to be that might be creating gaps for some of our learners are, you know, at risk students. We’re actually creating gaps for all students, if our tier one instruction is not rigorous and on grade level.

Kyle Pearce: Hmm. And what that means is when you say tier one, that also means that, you know, if we want to do this well, it means that we’re going to have tier two and tier three supports in order to make sure that we assist those students who may not be at a place where they can get to that standard at this point in time. So very clear on our language here is that this isn’t a students never going to get there. It’s that maybe at this exact moment in time,

that’s not happening. But you are so right. want everyone right now who’s listening to envision that student that’s in a classroom where their current level of understanding, they’re actually not being pushed. I think, and maybe some of the people listening, maybe you are that student. Maybe you were that student, where you remember sitting in a classroom and not really feeling like you had to pay a whole lot of attention. And you could just get through. That actually

did a disservice, right, for that particular individual student. And I know that we all tend to look at those students who are struggling the most because we want all students to be successful. But you’ve highlighted a really important piece here, which again, if we want something like that to take place, I think landing in that high alignment, high autonomy place in this matrix or on this graph.

is going to be so important for that to land in a positive manner, in a productive manner. And of course, it’s not an overnight thing. This is where, you know, looking as a school, as a district and looking and planning and looking and saying, what is our vision? What is, what are our goals? And how are we going to get closer to some of these goals along the way and making sure that we can build

the alignment because alignment isn’t something that we can just enforce. We need to build that alignment and we also want to keep autonomy at the table as well so that every stakeholder, educators in particular, are feeling like their voice is valued.

Yvette Lehman: So let’s discuss maybe a couple of moves to support alignment and then a few moves to support autonomy. So I mentioned common assessments. Again, that is not something I would have even entertained a year ago. So as I mentioned, I’m really shifting my own beliefs around why that’s important. I think a high quality resource or curriculum is important. You know, that all teachers have access to a high quality textbook or resource helps create alignment.

I think pacing guides that are not restrictive as far as to the day or to the week, but overarching, almost like benchmarks or milestones throughout the year so that we can ensure that our pace is going to allow us to create the learning that we need to create at that grade level during that year. I think those are three moves that we can do to support alignment.

Kyle Pearce: I think also, you know, as like, so whether it’s through say a pacing guide or through something else, when we do planning and we plan the order in which we’re going to deliver content or curriculum, looking at the curriculum and actually trying to get everyone on the same page as to what is the real goal here? What is like, what is the most like, what is important here? And what is less important, right? Whether you want to call it essential standards or

high priority standards. Now this isn’t about, you know, sort of leaving anything out, right? And I think sometimes when people go down this rabbit hole, they’re worried about being, you know, accurate, correct, wrong, right? All of these things. And it’s more about just really getting to the big idea of what it is that we really are doing this work for. And that can also give the and leave the autonomy in the teacher’s hands to sort of decide whether, you know,

I’m gonna go a little bit less on this area because I need more time. My students need more time on this very big, very important concept from this unit, this chunk of the course, whatever it might look like and sound like.

Yvette Lehman: And then I think, you know, as far as autonomy, that always goes back to building teachers capacity to provide responsive instruction. So that’s our ability to have ongoing formative assessment. And you mentioned identify students who may be struggling to access the concept providing targeted responsive.

small group instruction to help them. Some of the research I’ve read, it’s like on ramp them to the grade level learning. Like how are we going to take them from where they are and move them as close to the on level learning as we possibly can in this time. So, and that’s where, you know, I think I want to restate it just for clarity and also because I’m still grappling with this idea having taken such a huge swing in my own beliefs on this is that, you know,

lot of alignment at that tier one level, but then a lot of relying on the teacher’s knowledge, expertise to identify students along the way who are going to need more time, more practice, more concrete, more support to be able to access that tier one instruction.

Kyle Pearce: Hmm. And I think this is to highlight what you had already mentioned about high quality instructional material. The same is true for tier two and tier three, because it’s one thing to give autonomy to an educator, you know, to do what they believe is right for a tier two or tier three student. But I would argue it’s even more difficult. You know, like that work is even more difficult than say coming up with a tier one lesson that they’re able to

you know, kind of lead and try to engage all the students. When we look at tier two and tier three, there’s a lot of understanding and content knowledge that’s important to have. So therefore having proper support so teachers can learn along the way, but then also be able to, don’t want quickly is the wrong word, but effectively, efficiently be able to draw timely and draw on these materials so that they’re able to.

when they do spend time with students in a smaller group setting or one-on-one setting, that that time is maximized, right? Because that time is so valuable, we can’t just hope and pray and roll the dice that the time I spent with this student is going to be helpful with this idea, this concept, or this skill.

Yvette Lehman: actually one of the big ideas in the book we reference all the time, Systems for Instructional Improvement. What they found through that research was that teachers needed to build capacity in their strategies to intervene in small group, particularly for historically marginalized students. It’s like that is capacity that we have to build in educators in order for this ideal, you know, bullseye that we’re describing to be possible. So in summary, it’s like we don’t want one or the other or neither.

We want to create consistency across the district. We want the rigor at the grade level to be clear. We always talk about we need to know the curriculum. We need to know what the objectives are by the end of the year and teach to a high standard, to teach to a high level of rigor. But in doing that, what we don’t want to do is rob teachers of their ability to be responsive and to do what they know is best for students because

every student, every class you teach is going to differ. And so yes, we can keep that tier one, you know, moving along using high instructional materials. Like I said, I advocate for common summative assessments, even if the thing I love about common summative assessments as well, and I’ll just throw this other pitch out there. Imagine how many more opportunities you’d have to moderate student work across schools, across great, right, right.

Kyle Pearce: across different classrooms, schools, 100%, 100%.

Yvette Lehman: So it just creates more opportunity for collaboration and building our own understanding of the expectations at that grade level.

Kyle Pearce: It’s like you’re giving an opportunity for other educators to kind of talk the same language, right? When we come together, because we are aligned, right? We are doing some of these same things. we’re essentially working as a team outside of our individual classrooms, which I think is huge. So friends, in summary, you know that there are six parts to your math program tree. And today, I think we hit on a lot of them.

right? But the one that I think is most important here is the trunk because we are talking about leadership. We’re talking about building the backbone of your program, whether it’s across the district, across the school or across your grade band. We are talking about, you know, some of the moves that are necessary in order for us to have sustained change and systematic change over time. So if you’d like to figure out which

part of your math programming tree that you’d like to strengthen and where things are going well so far, head on over to makemathmoments.com forward slash report and you can take our short assessment that will give you a handy little report and share some next steps for you. Of course, my friends, if you have not yet, a rating and review for the show goes a long way and we can’t wait to see you in the next episode.

Thanks For Listening

- Book a Math Mentoring Moment

- Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

- Leave a note in the comment section below.

- Share this show on Twitter, or Facebook.

To help out the show:

- Leave an honest review on iTunes. Your ratings and reviews really help and we read each one.

- Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, and Spotify.

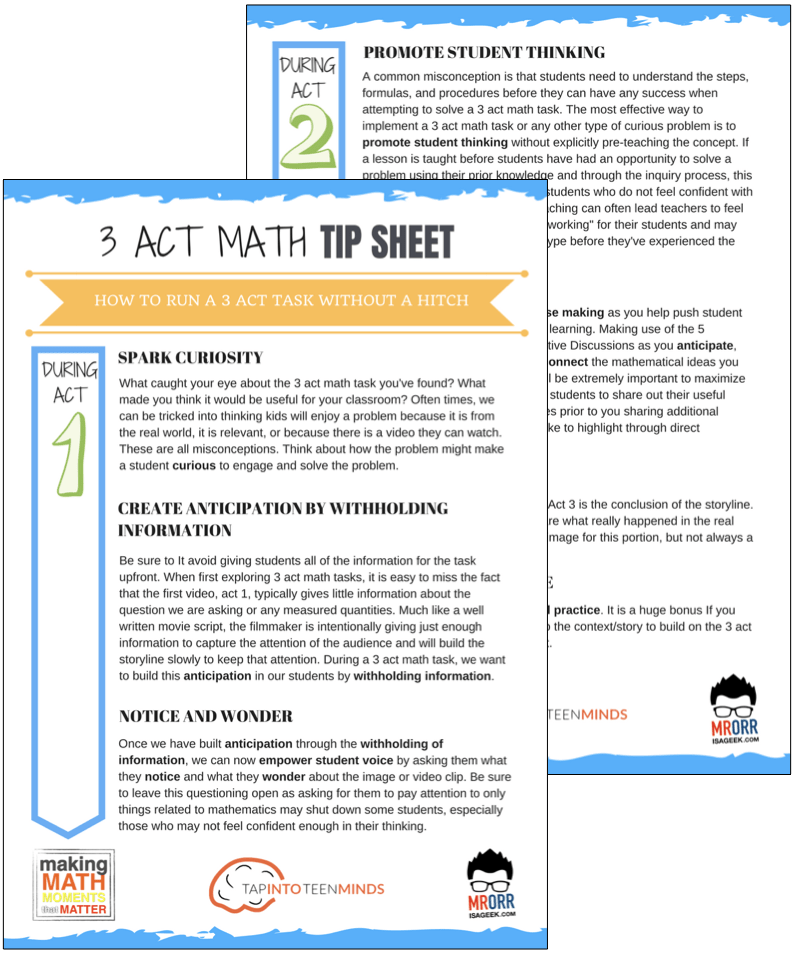

DOWNLOAD THE 3 ACT MATH TASK TIP SHEET SO THEY RUN WITHOUT A HITCH!

Download the 2-page printable 3 Act Math Tip Sheet to ensure that you have the best start to your journey using 3 Act math Tasks to spark curiosity and fuel sense making in your math classroom!

LESSONS TO MAKE MATH MOMENTS

Each lesson consists of:

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson consists of a Teacher Guide to lead you step-by-step through the planning process to ensure your lesson runs without a hitch!

Each Teacher Guide consists of:

- Intentionality of the lesson;

- A step-by-step walk through of each phase of the lesson;

- Visuals, animations, and videos unpacking big ideas, strategies, and models we intend to emerge during the lesson;

- Sample student approaches to assist in anticipating what your students might do;

- Resources and downloads including Keynote, Powerpoint, Media Files, and Teacher Guide printable PDF; and,

- Much more!

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson begins with a story, visual, video, or other method to Spark Curiosity through context.

Students will often Notice and Wonder before making an estimate to draw them in and invest in the problem.

After student voice has been heard and acknowledged, we will set students off on a Productive Struggle via a prompt related to the Spark context.

These prompts are given each lesson with the following conditions:

- No calculators are to be used; and,

- Students are to focus on how they can convince their math community that their solution is valid.

Students are left to engage in a productive struggle as the facilitator circulates to observe and engage in conversation as a means of assessing formatively.

The facilitator is instructed through the Teacher Guide on what specific strategies and models could be used to make connections and consolidate the learning from the lesson.

Often times, animations and walk through videos are provided in the Teacher Guide to assist with planning and delivering the consolidation.

A review image, video, or animation is provided as a conclusion to the task from the lesson.

While this might feel like a natural ending to the context students have been exploring, it is just the beginning as we look to leverage this context via extensions and additional lessons to dig deeper.

At the end of each lesson, consolidation prompts and/or extensions are crafted for students to purposefully practice and demonstrate their current understanding.

Facilitators are encouraged to collect these consolidation prompts as a means to engage in the assessment process and inform next moves for instruction.

In multi-day units of study, Math Talks are crafted to help build on the thinking from the previous day and build towards the next step in the developmental progression of the concept(s) we are exploring.

Each Math Talk is constructed as a string of related problems that build with intentionality to emerge specific big ideas, strategies, and mathematical models.

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Use our OPEN ACCESS multi-day problem based units!

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Partitive Division Resulting in a Fraction

Equivalence and Algebraic Substitution

Represent Categorical Data & Explore Mean

Downloadable resources including blackline masters, handouts, printable Tips Sheets, slide shows, and media files do require a Make Math Moments Academy Membership.

ONLINE WORKSHOP REGISTRATION

Pedagogically aligned for teachers of K through Grade 12 with content specific examples from Grades 3 through Grade 10.

In our self-paced, 12-week Online Workshop, you'll learn how to craft new and transform your current lessons to Spark Curiosity, Fuel Sense Making, and Ignite Your Teacher Moves to promote resilient problem solvers.

0 Comments