Episode #323: Math Fact Fluency: Must-Know Facts – An Interview with Jennifer Bay-Williams

LISTEN NOW HERE…

WATCH NOW…

Is Math Fact Fluency a term you’ve heard a lot lately when it comes to math education? Well there’s a good reason for that. There’s a massive campaign to help all educators understand what real math fact fluency means vs. just rote memorization and regurgitation math facts. One of the leaders of this campaign is Jennifer Bay Williams and she’s this week’s guest!

Many educators struggle with helping students achieve math fact fluency without resorting to rote memorization. This episode dives into proven strategies to build lasting understanding and confidence in math, equipping your students for long-term success.

- Discover research-backed strategies to teach math facts through understanding and relationships rather than memorization.

- Learn practical ways to engage students with games and activities that foster fluency and flexibility.

- Gain insights on assessment practices that value reasoning and help students develop a love for math.

Tune in now to uncover strategies that will revolutionize how you teach math facts and create a classroom where all students thrive!

Attention District Math Leaders:

Not sure what matters most when designing math improvement plans? Take this assessment and get a free customized report: https://growyourmathprogram.com

Ready to design your math improvement plan with guidance, support and using structure? Learn how to follow our 4 stage process. http://makemathmoments.com/discovery/

Be Our Next Podcast Guest!

Join as an Interview Guest or on a Mentoring Moment Call

Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

Book a Mentoring Moment Coaching Call

Are You an Official Math Moment Maker?

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Jon Orr: Hey there, Jenny, welcome back to the Making Math Moments That Matter podcast. Just before we hit record, were just quickly chatting about when the last time you joined us here, which we were like, my gosh, it’s it’s felt like a while. I think 197, episode 197, we talked with you, which would have been a couple years ago. And we’ve got you back, we’re excited. And Yvette’s here, she’s joining us as well. So we are excited to dig into your summit session that’s coming up.

or if you’re listening to this after the, you know, after the summit has already aired, we’re gonna talk all about, you know, must know facts about math, fact fluency with you. So what’s going on in your world these days and how you been?

Jennifer Bay-Williams: There’s a, well, I’ve been great. I’ve been traveling quite a bit. I just came back from Canada. I’ve been able to travel around the US talking about math back fluency and fluency beyond basic facts and loving that work and really appreciating how teachers are putting in the hard work to figure out other ways to teach students than just, you know, standard algorithms and, you know, drill. So that’s, you know, that’s been taking up most of my time.

Yvette Lehman: So as a veteran to this podcast, you know we love to start off by asking you about your math moment, something that has just really stuck with you and shaped who you are as an educator and a mathematician.

Jennifer Bay-Williams: So I’ll share one. As I was saying, I’m not sure if I shared this one before, but it’s so important to my place in education now I’m going to share it. And that is when I was a freshman in college, I was already taking math courses. Math was easy for me. But I was not going to become a teacher. I no idea what I was going to do, but I was not going to become a teacher. But I

went to a school to volunteer, an elementary school, and I was asked to work with a student who was struggling with, believe it or not, their basic facts. And so they’re like, can you help him? No manuals are given out for that. Just help him. You have 20 minutes or 30 minutes. So I did that. And I came back a week later, and the specialist met me at the door and said, what did you do with, I’ll just call the student John. Is that OK, John?

Jon Orr: Hey, that’s okay. John often gets picked on when we give examples. Johnny, it’s always Johnny too, right? It’s like, hey, let’s call on Johnny.

Jennifer Bay-Williams: Hahaha

Okay, Johnny. Anyways, I was, of course, first having hit the panic button that I had maybe, you know, not taught him well. I don’t know, because I didn’t know what I was doing. But as it turned out, he had done very well on his basic fact test he’d had after he’d been flunking them consistently. And the teacher really wanted to know what I had done. And so I…

literally felt so good for the next few weeks that when registration came, I signed up for my first education course. So that was a special moment because what it came down to is him being able to realize that he did know some facts. He didn’t just not know his facts. That’s how he’d been characterized, but he knew a lot of facts. He had to sort through which ones he knew and how to use that. Now it was years and years and years before I started focusing on basic facts, but it’s a special moment because I would not have gone into teaching had I not met Johnny.

Yvette Lehman: your moment actually hit on one of my burning questions for you. So this is a selfish one. I think so much, you know, is not yet understood about true intervention and what do we actually do when students start to struggle. And I was fortunate to get to hear you speak at NCTM this year. And one thing that I took away from that session was that the research-based approaches that, you know, you’re helping us to understand.

don’t just work for the middle or high achieving students. It’s about really reaching all students, in particular students who may be at risk or students who may have been perceived previously as not being good at math. So what is it about the research-based approaches that you’re supporting us in understanding that are helping us meet the needs of these learners?

Jennifer Bay-Williams: I’m going to start with a big picture response to that, which is whatever intervention you’re doing, if it’s helping the student make sense of what the math relationships are, it’s probably a good intervention. And if you’re skirting that making sense, you’re trying to get around it, here’s a quick fix, then it’s probably not a good intervention. It’s that you’re shortchanging the student in the way that that’s a short fix. But in the long run, that doesn’t hold up.

So as a specific example, if students are needing intervention with their addition facts, you can sit there with flashcards and drill them. And a few minutes later, they’re going to start remembering that fact because they just saw it, and maybe even a day or two later. But weeks later, they’re not. so memorizing is a weak learning strategy that’s well established in the research. And it certainly is one of those strategies that doesn’t work well with students who struggle.

A much better strategy is strategies. And so if you spend the time investing in them, knowing that number relationship, that nine is one away from 10, well, then if they know 10 and some more, you know, as a sum, then they know nine and some more. So I could give loads of examples, but that strategy instruction is teaching them an important number relationship that pays off later, that sticks with them. Maybe they just remember nine plus six, but if they don’t, now they know nine plus six is one less than 10 plus six or some kind of that’s going to help them.

Jon Orr: Yeah. Yeah. And I know that we’re going to chat about your summit session all around games and strategies and to strengthen basic math facts. And one of the things that I think often gets asked, and specifically if we’re talking about intervention or we’re talking about helping tier one instruction, like when we’re helping students with basic math facts, I think, when you think about those teachers who are like, when you said

focus, maybe stop focusing so much on memorization and focus on strategies instead. How do you, what is the language you help a teacher wrap their mind around that? Because so many teachers I think are still, and we get asked this question a lot with the districts that we work with about like, how do we help them help teachers see that strategies is the way to go and not memorization because so many teachers I think are still stuck in like, this is, this is going to work because it either work for them or they just.

They just don’t have the strategies in their pockets yet and they’re just not convinced. Like how do you help, you know, just help them see that this is the way to go versus, you know, sticking to the same old, same old.

Jennifer Bay-Williams: So one thing I would say is that, are you talking about how a fact gets learned or what the end result is, what the outcome is? So memorizing is a way that a student can get a fact down. So is working with strategies, right? So one is they memorize nine plus six and another is they have been thinking about these number relationships. Nine and six is the same as 10 and five and that sort of thing. And then ultimately the outcome for both pathways

is that they just know 9 plus 6, that they can recall that fact. helping, I think for all of us to be very precise about our language helps because memorizing is an act. Like you memorize a phone number, you memorize your security number, you memorize an address from staring at it and repeating it and repeating it repeating it. But our basic facts are number relationships. They’re about quantities that we’re adding or subtracting, multiplying, dividing. So we learn them by building

number relationships. And then the outcome is that we have this recall because we’ve done it so many times through. So recall, that’s an outcome, or automaticity, an outcome. How we’re going to get there, memorize, that’s bad way. Strategy instruction, that’s a better way.

Yvette Lehman: Think there’s also a lot of teachers out there that recognize that the way that maybe they’re currently going about it or the way that they were taught didn’t work. I’m one of those students myself where memorization was just never going to work for me because I have to understand to be able to recall for sure. But I also wonder sometimes if if that’s all I know, if that’s the way that I was taught, that’s how my pre-service training, my mentor teacher showed me.

but I recognize that I need to make a change, I know that I can do better by my students. I believe the research. What would you suggest is almost like an initial step for those teachers out there who are saying to themselves, I recognize there’s a problem. I know there’s a solution, but I just don’t know what to do tomorrow or next week to start to implement this change.

Jennifer Bay-Williams: So I have a book, a little purple book. It’s also in French. That book’s not purple. A Math Fact Fluency. That really is very reader friendly explanation of how to go about doing this in more detail. But simply, if that book is not something that a person wants to purchase, is to think about building on student strengths.

And so I have this learning progression that I’ll talk about in my session that is logical. So we start, I’ll switch over to multiplication. So for multiplication, we start with our twos facts because they come out of their addition tradition knowing their doubles as addition. So we start with that and think about how eight plus eight is now thought about as two groups of eight, two times eight and build the symbols and the language for multiplication.

to start there. And then we have place value understanding. So we moved our tens. And then fives, which are commonly skip counted instead of learned from memory so they can recall them, we can use our tens to work with our fives. So I think a good place to start is just thinking about these facts that are super important to later use the strategies. So for multiplication, that’s the twos, tens, fives, and then after those, the special cases of the ones and the zeros.

So I would recommend that. then there are the equivalencies with addition, starting with combinations of 10. Do students really know their combinations of 10? And not just that seven plus three equals 10, but that if I say eight, then you can say two. You know the distance to a 10. Because that’s the kind of automaticity recall you need in order to do the strategies.

That’s that intervention piece. Are they ready to do a strategy? Do they know those foundational facts before we move on to the other facts?

Jon Orr: Would you recommend like, I think when you’re helping teachers, you know, adopt these strategies in their classrooms, it’s like, think we’re often faced with one of the barriers, I think, is teachers either just don’t know the facts, but also aren’t comfortable with, say, practicing this because they didn’t learn it that way. And so they’ve got their own kind of history of the way they’ve learned math, and they’re trying to wrap their minds around these strategies. But then they’re like, I’m not going to, even though we just talked about which one to maybe to start with,

It’s like, do I start with those like on my own? Like, do I need to like practice this myself? like, or do I like, or should I just jump in with like two feet and like, and I guess that depends on the person because like, are you comfortable with like looking and feeling vulnerable in front of students or are you not? sometimes it’s like, I always wonder is like, is it, how much of this are we, are teachers being asked to do on their own? And then how do they take that step forward? Any recommendations for?

Think of specific like coordinators, coaches who were working with teachers. was like, how do I push the needle here to get more of this happening in rooms?

Jennifer Bay-Williams: I appreciate the question because teaching is so much about vulnerability. And in particular, if somebody else is watching you teach, including your students, but if you have other adults in the room, it’s even more nerve-racking and maybe parent volunteers or whatever. So it is about vulnerability to try something you’ve never seen done. And so for example, with teaching the basic facts, a good way to learn the strategies is through doing quick look images that have dot patterns or like

pairing up stories. And so you’re doing a number talk, but a number talk with a very specific purpose of teaching a strategy. And so we, I like to call it mucking about. We’re trying this out. Like that number talk didn’t go so good. Okay, well, tomorrow I’m going to do it this way. And then we just try it, try it again. And it’s then inviting to have another teacher there where you’re like, I’m to do it today. Could we like talk about like whether this helped? And then right after that,

Number talk, let’s say we’re working on the making 10 strategy or something. So we’ve just done these quick looks to help them see what that looks like. And then they’re playing a game. And so you can sort of observe whether your number talk went well or not based on whether students have picked up that idea you wanted them to and the number talk, which is very strong with visuals and stories. Can they use that in the game or they can’t? And if they can’t, then that’s your own self diagnostic.

How did that teaching go? Not very well. They’re all still counting on their fingers, right? Or let’s go back and redo that. So I just think that’s one of the beautiful things about teaching is that we are constantly asking ourselves, did the way I approach this subject work? And if not change it, like we just have to give ourselves the grace that there aren’t simple instructions to good teaching.

Yvette Lehman: I think you touched on a big idea as well that John and I, you know, mentioned all the time, the impact of that community, just having a community of educators invested in the same work so that we can visit each other and talk about what went well and do some co-planning. And that really comes from leadership, like having leadership that’s also supporting this work and creating the structures and space for there to be collaboration in a collective journey. One thing we were wondering,

actually John and I earlier today as we were prepping for this call was imagine you walked into a classroom where these practices were in place. It’s like the teacher has has adopted and implemented this approach. What would tell you that it’s happening? Like what would you see happening in that room if there was full implementation of this strategies based approach? What would be almost like the observable behaviors?

Jennifer Bay-Williams: All right, well, I’m imagining a number of classrooms I’ve been in because I’ve seen just some amazing teaching happening all over the place. I get to visit classrooms in lots of places. And so what happens is oftentimes you see early on in a lesson, the number talk happening, children around a circle. There’s quick look images being shared or story with relationships and students are being asked, you what do they see? What did they notice?

Is there another strategy they have? And then a few minutes later, they’re playing a game. They’re laughing. They’re saying their strategy’s allowed. They’re arguing over whether the answer is 13 or 12, like with a passion that you really don’t see when you’re doing a worksheet. And so they’re convincing each other what the correct answer is. And then the teacher is asking if they will

Now put that away so they can do the next thing and the students do not want to. So that is one of the most beautiful things when the teacher’s having trouble having them quit doing their math lesson because they’re so engaged in the activity or game that they’re playing. So that’s what I imagine when I see basic, real effective basic fact fluency happening.

Jon Orr: Right, right. You mentioned worksheets and I want to bring this up because I remember reading this and you’re figuring out fluency book series was that I think people often will, you hear like one side or the other in the worksheet camp. It’s kind of like either we are all, know, like am I using a worksheet or am I, no, I don’t use worksheets at all. But I mean, like I think one of my big takeaways from a part you wrote in that book was like there is sometimes a place for the practice and

And you can practice it with games, can practice it with different activities. what I think my big take away is like, worksheets can be purposeful if it’s very purposeful to the strategy you’re trying to bring about. I think what I remember was if the strategy we’re trying to highlight here today is how do I craft the questions they say on that practice sheet.

so that it brings out the strategy or like when we recognize that we’re not supposed to use the strategy, there was like a really nice fluid motion of like the way you outline like what a worksheet should look like if you’re going to use a worksheet. Because I think lots of people are like, no, I don’t use worksheets, but I mean, they have their place.

Jennifer Bay-Williams: They absolutely do. And I have spent a ridiculous amount of time trying to find a quality worksheet through Googling online. I’m not having any luck, because so many of the worksheets have way too little in the way of reasoning. I’ll just leave it at that. The instructions might say, solve using the standard algorithm. So if we just think, let’s just start with the instructions. There’s so many.

things we could do, like just draw a line right through that that detail there. Get your old fashioned white out out or use your technology tools to delete those instructions and instead ask questions like, solve using a mental strategy or solve using a reasoning strategy and otherwise solve with the standard algorithm. So they’re thinking, is there a more efficient way I could solve this problem?

Or the instructions could say, pick 10 problems on this page to solve. Make sure you use three different reasoning strategies on this page. So then they don’t have like, they don’t need to learn 30. mean, they don’t need to, right? So there’s some ways to navigate the instructions. Or look through this page and circle three that you think blank strategy would work. Like the making 10 strategy is one that generalizes to bigger numbers.

adding fractions, where could you use the make a whole strategy? Go circle the fraction addition problems where that strategy is a good idea. And then that’s helping them notice that their job as a mathematician, when they look at a problem, is to decide how to solve it, not to perform the standard algorithm that their teacher showed them. Their job as a mathematician is to make a decision. So if we can just frame the worksheet as make a decision. But therein lies the challenge.

Because when I said I went looking for worksheets, I was looking for ones where you could change those instructions. Only all the problems on the page were either stupid, like adding fractions with weird denominators. Why are we adding like 11ths and 7ths? I mean, you know, why are we doing that? But there aren’t those opportunities to notice, hey, I don’t need my standard algorithm here.

I could use something else. So if all the problems are messy, so they all lend to the standard algorithm, then it is just a rote exercise. And there are those days where you’re working on a standard algorithm or a days when you’re working on a strategy where maybe they are all lending to that. For example, another classic one is when you’re doing subtraction and there’s a 0 in the first number. We call that lesson regrouping over zeros.

regrouping involving zeros, whatever that is. That’s a method, by the way, not a concept. That’s a strategy in and of itself. But there could be two methods shown there. There could be the constant difference, there could be, or three methods, counting up and then regrouping. And then students, again, could be asked to solve one of the problems three different ways, decide which one they like, and then make sure they’re using the different methods. And at the end, explain back,

have a journal prompt at the end of the worksheet that says something around, are you noticing about when you want to use each of these strategies?

So that’s a long answer, but I think the key is if you do nothing to the worksheet, but just open up the option of doing different methods, then you’ve changed it into at least a reasoning task.

Yvette Lehman: And that really brings us to the big question I think we all have is around assessment. So what you’re describing with these worksheets is that we’re putting thinking central rather than, you know, mimicking or following a procedure. And so what is an effective way to capture that student thinking when we’re really trying to…

know, engage in assessment. In particular, I think where some educators might struggle is something a little bit more summative, where they’re trying to land on where this child is in the developmental trajectory. What is an effective way to gather that evidence?

Jennifer Bay-Williams: So whether it’s formative or summative, we have to move beyond just assessing accuracy. So you can’t just give a score of how the percent correct and be really measuring fluency. So the real challenge is to think, well, how can I assess efficiency and flexibility? So that’s where those prompts need to come in. If you ask them to solve these problems, choose an efficient method and solve these problems, then

you have your you at least have the possibility of assessing actual fluency, the efficiency, flexibility and accuracy. And you can do that a couple of ways. Like it’s easy to score the accuracy, you know, right or wrong. But the flexibility and efficiency can be scored on a rubric that just gets like attached to the page or you can give like a just make one up. know, three points means you demonstrated that you matched.

these problems with an efficient strategy and a two would mean you mostly match them up and one means you’re, you know, heavily reliant on, you know, one or two strategies, right? You’re not showing that efficiency or flexibility. So I think giving that feedback to the student, it’s an invitation to them, hey, we want you to be more of a divergent thinker, not just this do the same thing every single time. Think about this exact problem, how you want to solve it.

So if we give them feedback on that, we’re coaching them in the direction we want them to grow to become a mathematician.

Jon Orr: Totally, totally. And it’s like communicating like what you value. Like you can even say like have that particular assessment is like on you know what we’re looking for is because if we’re assessing and it is a paper and pencil say assessment, you know there’s nothing wrong with telling your students be like on these—on this assessment or on this day we’re looking for this and this is what we’re valuing here and like communicating that this is the way you know we’re gonna grade your answer and we’re really here to provide you some feedback so that you can—

You know, you take this and work with it and grapple with it. Like, I think we got a long way to go in terms of how we assess students and what we’re really looking for and what we’re really telling students we value. Because if you can be doing it in your classroom of like, okay, we really value fluency and basic math back fluency and we’re gonna do all these activities but we’re not shifting those assessment practices, kids pick up quickly on where the emphasis lies and then they’re just gonna drift towards accuracy anyway if you’re not.

you in your actual lessons and activities, because they know that come test time, or quiz time, or assessment time, you’re not, say, the actual elements of fluency, then, you know, it’s almost like, they’re not going to kind of pick up on what you’re trying to put down.

Jennifer Bay-Williams: I agree with you 100%. And the reality is it’s a lesson to ourselves too with basic facts that our outcome is recall of all the facts it is. But it’s also that they know these strategies because these strategies live a long life after the basic facts. So they can add nine plus six by thinking of it as 10 plus six and one less. They can add 99 plus 26 by thinking, that’s 126, one less. Those number relationships have a long life to support their reasoning and their flexibility. And so our outcome is both. So we have to assess and value their good thinking.

Jon Orr: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. You know, my big takeaway from our discussion here today is like that phrase you just said. It’s like the outcome is the same. Like, we’re trying to get to the same place to have this recall. But we have pathways to get there. And which pathway is the more valid, or not necessarily valid, but what is the more honorable and worthwhile pathway we should be taking with our students to get to that same outcome? We can go in these two paths. But which one do you really want to take down?

you know, go down for those students. What would you say, like your session’s coming up, you know, coming up at the time of this recording, if you’re listening to this and we’ve already done it, maybe you were participated in Jenny’s session. Jenny, what would you say is like your, what would be a big takeaway if folks are sitting in the session and they’re engaging with you? What do you hope that big takeaway is from the work that you’re going to do November 15th, 16th, 17th that weekend?

Jennifer Bay-Williams: that the research soundly supports strategies that build on students’ number sense.

Jon Orr: Awesome, awesome. That’ll be awesome to kind of witness. And I’m excited. This is one of my, think, most exciting sessions that I’m looking forward to. And we wanna make sure everybody knows that November 15th, 16th, 17th is the summit. is coming up at the time of this recording. And we can’t be more excited for that. There’s going to be, I think, 52 speakers over the course of the weekend at the time of this recording.

There are 15,000 teachers registered. So it’s going to be a blast over the course of that weekend. We want to thank you for joining us here today. And can’t wait to see you live again in that weekend. But thanks for your time, and thanks for sharing your awesomeness with the MathMovemaker community.

Jennifer Bay-Williams: Thanks for having me and I can’t wait for the conference.

Jon Orr: Thank you.

Thanks For Listening

- Book a Math Mentoring Moment

- Apply to be a Featured Interview Guest

- Leave a note in the comment section below.

- Share this show on Twitter, or Facebook.

- Leave an honest review on iTunes. Your ratings and reviews really help and we read each one.

- Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, and Spotify.

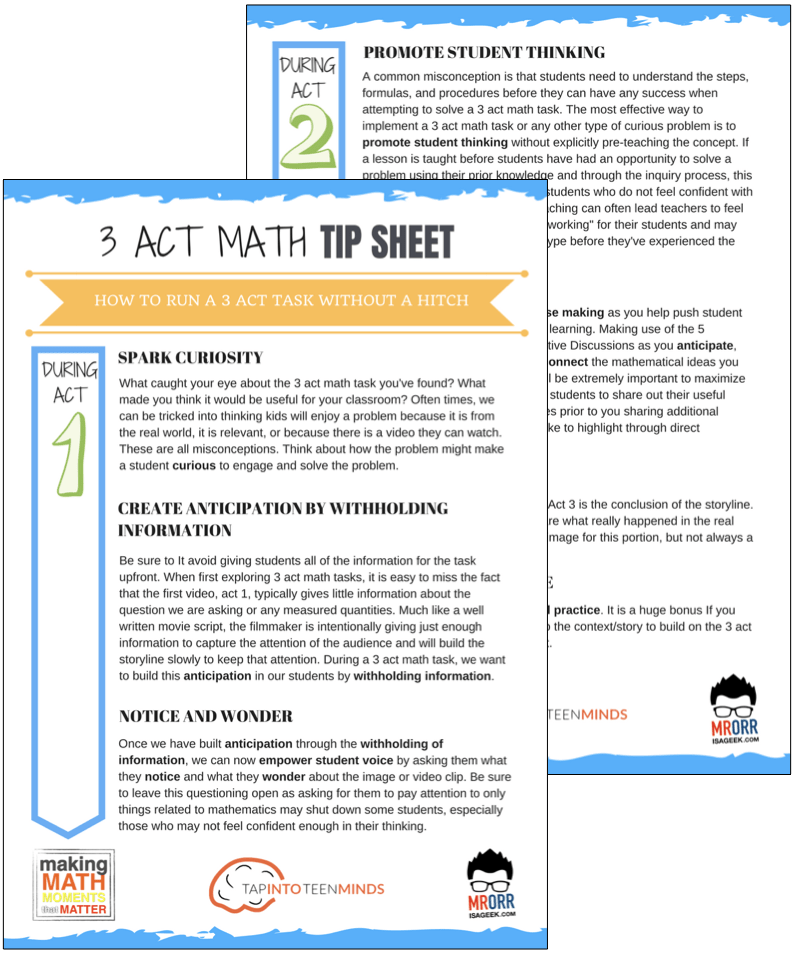

DOWNLOAD THE 3 ACT MATH TASK TIP SHEET SO THEY RUN WITHOUT A HITCH!

Download the 2-page printable 3 Act Math Tip Sheet to ensure that you have the best start to your journey using 3 Act math Tasks to spark curiosity and fuel sense making in your math classroom!

LESSONS TO MAKE MATH MOMENTS

Each lesson consists of:

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson consists of a Teacher Guide to lead you step-by-step through the planning process to ensure your lesson runs without a hitch!

Each Teacher Guide consists of:

- Intentionality of the lesson;

- A step-by-step walk through of each phase of the lesson;

- Visuals, animations, and videos unpacking big ideas, strategies, and models we intend to emerge during the lesson;

- Sample student approaches to assist in anticipating what your students might do;

- Resources and downloads including Keynote, Powerpoint, Media Files, and Teacher Guide printable PDF; and,

- Much more!

Each Make Math Moments Problem Based Lesson begins with a story, visual, video, or other method to Spark Curiosity through context.

Students will often Notice and Wonder before making an estimate to draw them in and invest in the problem.

After student voice has been heard and acknowledged, we will set students off on a Productive Struggle via a prompt related to the Spark context.

These prompts are given each lesson with the following conditions:

- No calculators are to be used; and,

- Students are to focus on how they can convince their math community that their solution is valid.

Students are left to engage in a productive struggle as the facilitator circulates to observe and engage in conversation as a means of assessing formatively.

The facilitator is instructed through the Teacher Guide on what specific strategies and models could be used to make connections and consolidate the learning from the lesson.

Often times, animations and walk through videos are provided in the Teacher Guide to assist with planning and delivering the consolidation.

A review image, video, or animation is provided as a conclusion to the task from the lesson.

While this might feel like a natural ending to the context students have been exploring, it is just the beginning as we look to leverage this context via extensions and additional lessons to dig deeper.

At the end of each lesson, consolidation prompts and/or extensions are crafted for students to purposefully practice and demonstrate their current understanding.

Facilitators are encouraged to collect these consolidation prompts as a means to engage in the assessment process and inform next moves for instruction.

In multi-day units of study, Math Talks are crafted to help build on the thinking from the previous day and build towards the next step in the developmental progression of the concept(s) we are exploring.

Each Math Talk is constructed as a string of related problems that build with intentionality to emerge specific big ideas, strategies, and mathematical models.

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

Use our OPEN ACCESS multi-day problem based units!

Make Math Moments Problem Based Lessons and Day 1 Teacher Guides are openly available for you to leverage and use with your students without becoming a Make Math Moments Academy Member.

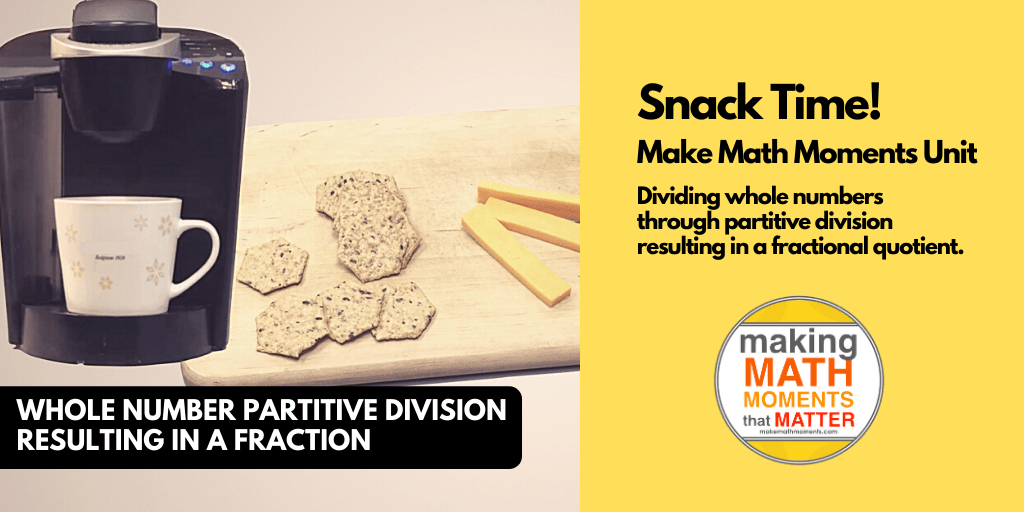

Partitive Division Resulting in a Fraction

Equivalence and Algebraic Substitution

Represent Categorical Data & Explore Mean

Downloadable resources including blackline masters, handouts, printable Tips Sheets, slide shows, and media files do require a Make Math Moments Academy Membership.

ONLINE WORKSHOP REGISTRATION

Pedagogically aligned for teachers of K through Grade 12 with content specific examples from Grades 3 through Grade 10.

In our self-paced, 12-week Online Workshop, you'll learn how to craft new and transform your current lessons to Spark Curiosity, Fuel Sense Making, and Ignite Your Teacher Moves to promote resilient problem solvers.

0 Comments