Episode #26: How To Overcome A Common Math Myth From K Through College

LISTEN NOW…

You’ll Learn

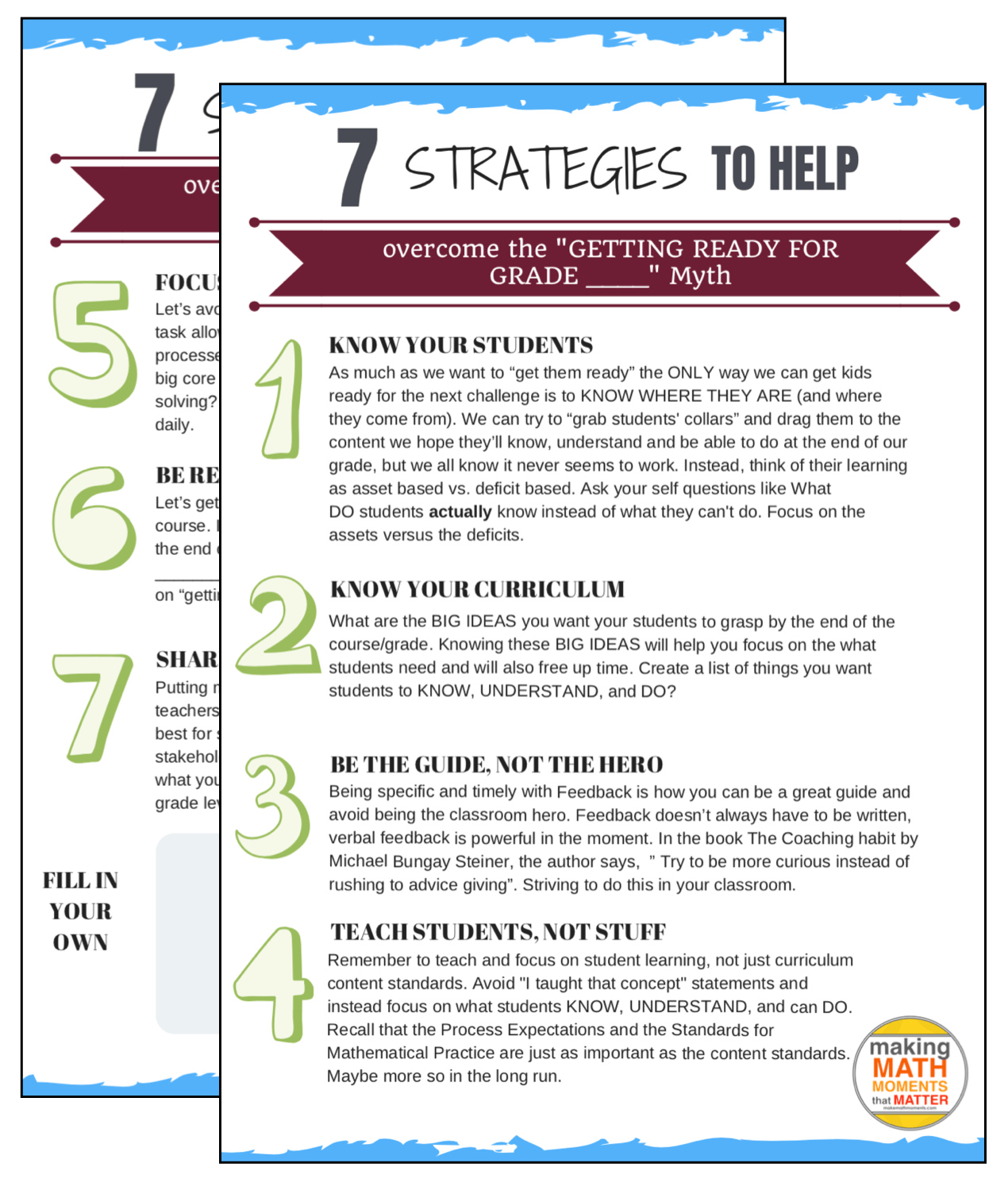

- 7 Strategies to help overcome the “I have to prepare my students for grade _____”

Myth. - Why this myth hurts student learning.

- How we can use explicit strategies to overcome the myth.

- Tips on how to communicate your teaching beliefs with the stakeholders of your classroom.

Resources

Grab THE PDF CHEAT SHEET

We'll send you the two-page PDF cheat sheet from the episode. We'll also keep you updated with weekly emails.

- Multiplication Squares Game

- Concept Based Mathematics [Book – by Jennifer Wathall]

- Every Math Learner [Book – by Nanci N. Smith]

- The Coaching Habit [Book – by Michael Bungay Stanier]

Learn to see if your Make Math Moments Academy is right for you.

FULL TRANSCRIPT

Download a PDF version | Listen, read, export in our reader

CLICK HERE TO VIEW TRANSCRIPT

Kyle: Next on the Making Math Moments That Matter podcast you’ll get to spend some time with Jon and I as we share the story of a recent school walkthrough that we participated in while recently attending a conference.

Jon: Any time we get a chance to hop into other schools to see the great things going on in math classrooms we are thrilled. While this particular experience was a fantastic one, it didn’t take long before we ran into a teacher who shared some unproductive beliefs in a common math teaching myth as we toured through this school.

Kyle: What math teaching myth might we be talking about? You’ll find out in episode 26 where we’ll dive into this unproductive belief that holds many of us back as we try to do our best to help our students achieve at high levels.

Jon: Well, let’s get on with it.

Kyle: Hit it. Welcome to the Making Math Moments That Matter podcast, I’m Kyle Pearce from tapintoteenminds.com.

Jon: I’m Jon Orr from mrorr-isageek.com. We are two math teachers who together-

Kyle: With you the community of math educators worldwide who want to build and deliver math lessons that spark engagement-

Jon: Fuel learning.

Kyle: And ignite teacher action. Welcome to episode number 26, How to Overcome a Common Math Myth from K through College. Are you ready for this one, Jon?

Jon: Oh yeah, oh yeah. This is a big one. This is a passionate one for us. I can’t wait to get into this.

Kyle: All right, all right. Well, before we begin the episode today we want to take a quick moment to invite you to check out the Make Math Moments Academy. We’ve had over 250 founding members join the academy in just two short weeks. Those educators have already started sharing their past successes, challenges, and their goals as they plan to continue developing their math pedagogical practice and improving their content knowledge in the community area. Some of us are already hacking away on our latest mini course titled The Concept Holding Your Students Back, while others are using our brand new curiosity task tool that has exclusive tasks with full teacher walkthroughs. Join the Make Math Moments Academy so you too can eliminate the guesswork and stop throwing everything you’ve got at the wall in hopes that something might stick. Learn more about the academy to see if it’s a right fit for you. Learn more at makemathmoments.com/academy. That’s makemathmoments.com/academy.

Jon: All right. Now let’s dive into today’s episode about overcoming a common myth from K through college. Well Kyle, what exactly are we talking about here? Let’s get into this story. We’ve been a little bit mysterious.

Kyle: Yeah, it’s a bit of a mysterious title for sure. This podcast episode idea actually came to Jon and I a few weeks back when we were doing a walkthrough of some elementary school the day before our conference started. It was super cool. Jon, what were some of the key highlights you saw as you were walking through some of the classrooms that day?

Jon: One observation that stuck out in particular was a grade four teacher. She was rocking the vertical nonpermanent services. We walked into this class and kids were at the boards, in groups, talking about strategies. They were all working actually. Each work was working on a different number sense problem on fractions, I believe, if I’m remembering correctly. What particularly stood out to me was after the work at the boards she had them come back to their desks and they consolidated quite well. There was sharing strategies out for each of the different problems on the board. Not just one for each problem, but different ones from the different problems and kids were talking about those strategies that they did and what was good about them, what was different about them. This teacher did a really good job of bringing out the important ideas of the math learned and then she was asking questions that brought that out. That was very, very nice to see and some of the things that we tend to overlook is that consolidation at the end of a test.

Jon: Sometimes we get our students up at the boards to practice and problem solve while they’re there and then we’re like, “Okay, let’s now just keep doing that at the boards or we can come back to our seat and do it some more.” We need to pay careful attention-

Kyle: Move onto the next one.

Jon: Yeah, careful attention on how we consolidate the strategies the students have shown each other and us.

Kyle: That was great. I know the exact classroom you’re talking about Jon. You and I both had a great opportunity to chat with that teacher after and I was very honest with her. I was walking around and I was sitting with groups of kids and they were great. These kids were essentially like … They were reasoning and proving to one another. They were trying to convince each other. The questions were very rich. What I tend to do as well is I try to ask questions to see the depth of understanding that these students have. Everything I was throwing at these kids it was like if they weren’t sure they did some more work. I came back and they were so excited to talk more about it. That’s not something just because there’s a walkthrough going on that the teacher’s like, “All right, I’m going to put the show on today,” like we tend to when there’s a walkthrough a school. Everybody’s wearing their best and they’re doing their best. They have their best lesson all ready to go.

Kyle: That’s something you can’t fake with students because students either have that culture or they don’t and I thought that was really cool about that particular classroom. For me, one of the ones that stuck out was actually the grade five class. I believe it was the same school. We went to three different schools that day. This particular teacher … It was a grade five class and there was a number talk going on. It was really cool. She had an array and I really liked because this number talk wasn’t just mental math. It was actually she used visuals and she had an array up on the screen which was four rows by six columns of pizzas. She had students sharing different strategies for how they could come up with the total number of pizzas first and then she flipped it around saying and asking them to try to use division sentences in order to chop it up in different ways. That was really cool.

Kyle: They went into stations after the math talk, so it was clearly a day where they wanted to do some purposeful practice and then she could work in small groups. I thought that was really cool. One game that caught our eye and I know you-

Jon: Mm-hmm (affirmative). True.

Kyle: … really liked this one too. Jon, what was the game that we saw that both of us … You and I both grabbed pictures of it because we were like this is a really cool one, we could probably adapt it for some of the secondary classrooms.

Jon: It was a game adapted from a game I used to actually play as a high school student to pass the time in our boring classes. We would put a whole bunch of dots on a paper in a grid, like an array of dot paper and we’d just make up our own dots so it was a big rectangle. We would take turns on connecting the dots to make line segments. You’d randomly do this and if you connected a group of four, you made a rectangle then you owned that box. That was your box. You put your initials in it and then you would get to go again. You do this game over … When you’re making moves at the beginning it’s kind of like blind, the gray is pretty big, but then when it gets down to it, it gets pretty intense because you’re connecting a whole bunch of boxes, one after the other. Now, this game, in this particular class, though, this wasn’t dot paper. This was an array of numbers and they were randomly put … not random numbers, but they were definitely-

Kyle: I think it was numbers 1 to 36.

Jon: Yeah. [crosstalk 00:07:57].

Kyle: You know it could be … I guess it would be-

Jon: That’s right. You-

Kyle: … 1 to 36.

Jon: The students were rolling a die and the numbers were in the grid, but they also still put a line segment on one of the numbers. There was multiple numbers. It wasn’t just 1 to 36, there was a whole bunch of 36s and a whole bunch of fives or fours. The student would still put a line segment on an edge of the number, the same way that my game play when I was a kid, so they could choose which number to put that edge on and then the same rules apply in the sense that when you complete a rectangle or a square you own that box and put your initials in it. Whoever has the most boxes at the end wins, gets all the points, let’s say. This was pretty cool because the students are rolling the dice to create the multiple line, but then choosing one of those numbers wisely and strategically which if you guys remember an episode, we had Dan Finkel on. He talked about games in math and he had some strategies-

Kyle: Yeah, that’s episode 11, I think.

Jon: He had some strategies on what makes a good game and one of the key strategies that sticks out for me is choice, having choice in the game, so that you could do some strategy, kids would want to play that. This game had that choice. That was nice to see. We talked briefly on how we would modify that game to high school and I think we were thinking exponent laws and we’re still working out the details on that and how we could use that for exponent laws, but great game in that class.

Kyle: Yeah, seems like at the core of it there’s so many different things you could do and obviously modify it as you see fit. I love when I see the opportunity for students. Not only does it open up an opportunity for teachers to work in small groups with students, but then it also gives students an opportunity to build their fact fluency and start to build automaticity. It’s not just blind rote memorization. The kids were loving it. When she had them switch stations, kids were actually disappointed. That, to me, is the key to having a super great culture and getting kids to feel like the classroom is a place where they’re actually learning and doing and learning through doing, instead of just sitting and getting, so that was really cool.

Kyle: But where this episode came from and, Jon, you know what I’m talking about. We walked into one class, it was a Kindergarten class and I mentioned on the podcast before coming from secondary and I know, Jon, you were really eager to get into an elementary class as well or an elementary school because you’re coming from the secondary side. I love getting into Kindergarten because I just like … In my head, I’m like, “Oh, I have so much work to do if I had to be a Kindergarten teacher.” I don’t know just where to start. We walked into this classroom and Jon, what was going on? When we first walked in there it was like I want to stay here. It just felt so welcoming.

Jon: Yeah, it was welcoming. The teacher was so polite in speaking to the students and the kids respected him and you could see that. Kindergarteners, sometimes when you walk into the classes you’re not sure about that, but they loved this man. He was treating these kids so nice. I think they were getting ready to move from the carpet to their desks and he did a great job of making this a nonthreatening environment. They moved in small groups to get to their coloring page. I think they were going to go color at their desks. This was great. The vibe was awesome.

Jon: But then I think that’s when we heard him say something interesting, Kyle. That’s when he turned to us and he said, “There’s been too much P-L-A-Y going on in here.” You see, he told us after that he was filling in for a teacher who went on maternity leave and he’d only been there for a few weeks and he was saying that there had been too much play going on here and he knew because he had been teaching grade one. He had been teaching grade one for over 20 years. He said, “I know what they need to get them ready for grade one.” As soon as he said that line, I had these images. I know what I need to get these kids ready for grade one. I’ve heard that phrase before and I’m sure you have heard that phrase before listening at home right now. I hear that phrase as a high school teacher saying-

Kyle: I used to say it. I was the guy that said it. I used to teach grade 12 and I was like, “Got to get them ready for university.”

Jon: Right. And the grade eight-

Kyle: And it’s just-

Jon: Grade eight teachers are saying, “I got to get them ready for high school.” Grade nine teachers are saying, “I got to get them ready to take grade 10.” Everybody is saying this phrase and this is what we want to talk about on this episode today that it’s the phrase that we say that’s holding us back from moving forward. We’re scared to do things. It’s a mental thing that we have to get our brains wrapped around because we say this phrase because we think the teacher in the next room, who’s teaching grade 10 or whatever the next grade happens to be. Is it grade four? Everyone says this. Because as a teacher, you know that you want to do a good job for your students but also in the back of your mind and maybe in the front of your mind you’re hoping that the teacher next door thinks you’re a good teacher too when your kids go to that class next.

Jon: Whether they’re moving from the grade 9 class to the grade 10 class or the grade 8 class to go into high school or even with a grade 12 going to university. You want those people, those teachers to go, “Hey, I got the kids from Mr. Orr’s class, they’re going to be really smart. They’re going to be … They’re on the ball.” You don’t want them saying, “Oh, oh, man, I got Orr’s kids, oh man, this is going to be rough.” I think it’s that phrase, Kyle, that makes people so concerned about I got to get them ready for the next grade. It’s this mental shift that we have to think about. We have to choose what’s good for our kids in the moment. We definitely want to talk about this particular issue on this episode, because I think it’s so widespread.

Kyle: I want to back up too and, Jon, I don’t think it sounded this way at all but I want to make sure we are crystal clear that, again, that teacher clearly had a lot of amazing things going on that room. Sometimes, even when we say those things sometimes how it happens it might not happen the way we’re saying them but I guess what we’re trying to do … It just gave us this we’re concerned. Because we know for a long time we were looking and we were thinking about our courses in ways where we were so hyperfocused on getting them ready for way down the road, which is a year away or is it a half a year away or maybe it’s four months away until the next grade. But at the end of the day it’s like we need to not let that fog our vision of what we need to do for our students. Because what we want to do is what’s best for them now and what’s best for them now is the key.

Kyle: Sometimes too, and this is extending this idea, we often think about this idea of well, next year they’re going to blank. It connects to this because it’s like well, next year they’re not going to do this or next year you’re not going to be able to do that. But at the end of the day, it’s like that’s next year, maybe it could be helpful to do that thing now in order to help them get ready for when maybe that thing is or isn’t there in the future.

Kyle: This episode, we want to really share some strategies to help us overcome. What we’re going to say is a mindset shift. It’s not that we’re not trying to help kids get ready for next year. I want to help kids get ready for 10 years from now too. I want to get them ready for all this stuff. But number one on our radar is to get them ready for today and then next on my radar is tomorrow. We’ll talk about that through these seven strategies. Jon, should people be jotting all this down? Should they be pulling their cars over right now or stopping their jog or do we have anything for them-

Jon: No.

Kyle: … that they’ll be able to [crosstalk 00:15:44] to make this easier?

Jon: No, Kyle. We want you to just listen to us now. What we have is we’ve jotted all these notes for you. We’ve taken the notes for you. You can go over to our website to download a page that’s going to summarize each of the strategies that we’re going to talk about today so that you can help your students learn math now and not necessarily worry about always preparing them for the next grade. I think, Kyle, just to add to what you said there about that preparing for the next grade is the idea that if that’s all we’re thinking about, then that’s a problem, right? If I’m only concerned about getting them ready for grade 10, then I have to take a step back because like you said it’s about the kid, but it’s also about what are the values and beliefs that you hold true about teaching math. We’ll get into that as we [inaudible 00:16:37] the strategies, but I think you have to decide what do I view teaching math. What is teaching math really? Those are the things that you want to answer and do you want to teach math or do you want to teach getting kids ready for grade 10. It’s a blend, it’s not I only should be thinking about grade 10 if I’m teaching grade 9. It’s about your beliefs. What do you want your students to get out of your class? I think that’s the important part.

Jon: We’re going to go through seven strategies here today. We’re going to put them over on the show notes page so you can do that. Makemathmoments.com/episode26. That’s where you can go and you can click. We got the PDF download for you so that you do not have to take notes here. Just listen. Also, think about how you can push back on some of these. We’d love to keep this conversation going. We’re going to have some details at the end of this episode on how you can do that too. All right. Here we go, Kyle, let’s get into this.

Kyle: Yeah, let’s look at strategy number one, which we’re going to call Knowing Your Students. Jon, you just said it, as much as we’re trying to get kids ready, the only way we can get them ready for the next challenge, which might be going from Kindergarten to grade 1 or from grade 12 into post secondary is to know where they are and that means knowing where they’re coming from. Where are they now? The reality is we know kids are at different places, so how am I going to actually accomplish that task of getting them from where they are now to where I’m in my mind. I’m thinking I want to get them ready for that next challenge, but at the end of the day, it’s like how do I get them ready for this challenge? Are they even ready to be tackling that challenge?

Kyle: I, for years, used to grab kids by their collar, I used to say, and drag them to the content and hope that just through repetition over and over and over again that they’ll get it. When I said get it, the problem was I didn’t actually do anything to help them understand it any better. I just was hoping that they would know it, like “know it” but not actually understand it and that’s a fundamental issue. We really have to think about what do they actually know. I’m wondering, Jon, what are some things I might do in my classroom to actually help me learn what they know? What could I be doing throughout my math lesson?

Jon: Good question, Kyle. We’ve talked about this many times on this podcast about avoiding the rush to the algorithm, going straight to procedures, opening up your lessons to allow for discussion, creating that culture in your room. You could flip back to many of our episodes where we talk about a lot of those things because I think all of those things about creating that culture in the room of discussion, of collaboration, allows students to work … allowing them to work together, but also listening to them. If you’re beginning your class with warmups the way we’ve talked about it before, like a notice and wonder warmup or a number talk warmup or an estimation warmup. Hearing what they’re saying is so important for understanding what they know before you begin any lesson. Because basically you’re grabbing and you’re making formative assessments on the fly. You’re understanding what they know. You’re deciding what kind of a problem solver they are when you hear these strategies being talked about even estimation problems.

Jon: In our three-act math problems, with always open the doors to what do you notice, what do you wonder, and then when we ask for more information we always add the line if I gave you that piece of information what would you do with it? That line right there is so important to listen to what the student’s say because that tells you what they will do. They’re formulating problem-solving steps right there. If the kid says like “I don’t know” that tells you information too, which is really valuable to know about that student. We can’t push kids. I get what you said about dragging them by the collar because I used to plan my lessons exactly that way. I was like, here’s example, example, example, example. I’m just going to go through it regardless of who’s sitting in front of me and then I will say, “Now you’re going to do 20 them” and I just go walk around the classroom and then everyone’s throwing up their hands at some of the tougher questions anyway, so that didn’t match exactly the example. Knowing your students is so important and I think that can help a lot because it’s all about moving that kid forward. Everyone’s on these different paths. I’m more focused on moving all the students forward, one at a time, on the path that they’re on.

Jon: So many of our students, you know Kyle this, and I know all of you know this, that when you’re teaching your grade you’re not teaching your grade, you’re teaching seven different grades. This Is especially true in the grade nine applied program. Here in Ontario you got students at varying grade levels. You’re saying I’m going to take a kid who’s operating at a grade 4 math level and I’m going to make him ready for grade 10. That’s the phrase that we’re staying, we’re going to get these kids ready for grade 10.

Kyle: You just said that.

Jon: Yeah, I’m-

Kyle: It’s not realistic that you just said it.

Jon: Right. I want to take that student and I want to push them along their path. I have the curriculum content to cover, but I want to move that student along their path and understand what they know so that I can help them the best. Knowing where they are and coming from is so important.

Kyle: What I look at this as, and you gave a great example, if a student is working at a grade 4 level and we’re talking about trying to get them to grade 10, for example, that is such as a huge daunting task. Again, of course, we want students to achieve at very high levels but that makes the job so much more challenging when I think of it that way. What I’m hearing here is if we start with what do kids know, going from the asset base. It’s so easy for us in education to think of the kids and what they don’t know. We always focus on what’s missing, the deficit. At the end of the day if we go, “Well, wait a second, what does this student know how to do?” I want them to do this, but they can do this. And then it’s like now what’s the gap in between? When I figure out that gap in between I go, “Okay, what is the very next step?” Because if I even try to get them in the middle of that gap, that’s still probably not going to be super helpful, especially if that gap is as wide as you describe. This is so, so important.

Kyle: I think this is a great bridge for us to talk a little bit about strategy two, which really comes down to knowing our curriculum. We’re not just talking about the expectations, but we actually want to know what are the big ideas that we’re hoping kids will walk away with. If we’re over focusing on the things that we want to them to know, which I did for the longest time. This idea of I want them to able to regurgitation certain facts or things or formulas in my math class. That, to me, was what I thought was important. If we actually zoom out think about what are the big ideas we want them to walk away with and what are the concepts we want them to understand and then finally what are those skills we hope they have and how are we going to actually help kids get there?

Kyle: This really ties in nicely to the idea of understanding the curriculum, but that also means understanding the content. Those are, to me, very different things because curriculum gives you an idea of what topics you’re going to use in order to elicit mathematical thinking, but at the end of the day, if I don’t understand how the concepts develop it makes it so much more difficult for me to try to help students move from where they currently are to where I’m hoping to help push them to over time.

Jon: That’s something that I learned just recently with listening to and talking with Cathy Fosnot and understanding the landscapes of learning on certain big ideas on where kids might be on that trajectory and where you want to go. That’s so important. Knowing the curriculum and knowing all that content is extremely important. Something to add to knowing the curriculum so well, if you know that content so well and that takes time. We know that that takes years for you to develop that. As a high school math teacher, I used to think that I know all the math, yet I didn’t know those landscapes. I didn’t know the progression of how learning is going to happen along from proportional reasoning to linear relations. It wasn’t something that I ever thought about. I just thought, hey, I just know how to solve linear equations or represent linear relations on graphs. I didn’t think about the progression. That takes a lot of time and experience to understand that.

Jon: What I find very relieving about deciding that I’m going to know my curriculum and content well and when I also think about I’m not going to just teach to get ready for grade 10 or university, I’m going to teach the kids I have in front of me. Knowing that content and curriculum so well helps me with time itself. It frees my time up to, hey, we’re working on this task today and we’re talking about proportional reasoning here and half the kids already showed me that they’re at this stage in this landscape. Some of them I can move from there to there in this particular lesson. If you can see that and know where they’re coming from and you can see all that and assess the kids where they are and that you can make that decision to mean actually I don’t have to plan the way the textbook has organized it. This is going to be freeing. This is going to allow me to save some time to explore concepts at a deeper level. I found that to be very relieving. The only way that that can happen, though, is if you know your content very well.

Kyle: Absolutely. Both of us have been looking at some different books and we’ve had some authors coming on the podcast and actually recently we interviewed Jennifer Wathall from her book Concept-Based Mathematics. She’ll be episode 29, I believe. Also, another book I’ve been looking at is Every Math Learner, the K to 5 version, but there’s also a 6 to 12 version by Nancy Smith. In both of these books, they reference this idea of how you might plan your content. It’s organizing. They use the word units, but we’re not necessarily saying it has to be a traditional unit, but this idea of a unit of study. They use three categories. This idea of know what do you want students to know. What do you want them to understand and what do you want them to do? Which I essentially referenced earlier when I introduced strategy number two, this idea of the big ideas and what we hope kids will actually know afterwards. I called it that regurgitating. Also, what skills do we want them to have or what they can they do after.

Kyle: They talk about these three things and to me by thinking about those three categories it starts to make me go what is it that I hope they understand. For understanding, to me, that’s making connections. It’s hard to unlearn things that you understand well, right? It’s like you understand it like a neighborhood that you grew up in. It’s like you know all the nooks and crannies of that neighborhood so even if you aren’t there for a while, it’s like you know it so well that you could make your way around it. To me, that’s a big area we need to be thinking about when it comes to our content. This is stuff that we should be doing before our actual school year begins or even our new semester begins. I know this podcast is coming out as we’re into summer for some of us and us Canadians are heading towards summer.

Kyle: These are things for us to think about over the summertime and plan out what is the content and then what parts of the content do I want kids to know, have that certain facts that they need to know like metric … I need kids in grade six to know that there’s 1,000 milliliters in a liter. They got to know that. That’s one thing they got to know. But I want them to understand how unit conversion works and that different units will provide me different measurements. The larger the unit the less of them I need. These are big ideas that I want them to take with them. These are things that I think can help us help get to that place of preparing them for the next step in the journey, but let’s do it in smaller chunks. How about strategy number three here, Jon? I think we’re ready to move onto that one. What is strategy number three to help us out here?

Jon: Okay, so strategy number three is be the guide, not the hero. We’ve talked about this a little bit before in our latest webinar that you’re not the hero in the classroom, the student is the hero in the classroom and you are the guide. Your job is to help them along their path. This is how it relates to strategies one and two already is that we’ve talked about knowing your students and where they are on that path and helping them along. But, strategy number three being the guide is all about what feedback you are going to give your students at the right time. Kyle, what are some good strategies for feedback to students that our teachers can take away with them right now?

Kyle: Yeah, like being specific and timely about feedback is super important. Something that I think a lot of people get overwhelmed with, I know I did, and I don’t know if I’m the only one out there that thought this, but I thought feedback had to be written and it doesn’t. It doesn’t have to be written. If I can create time just like that grade five teacher at that school visit that we went through. If I can find ways by creating activities that are going to help students through purposeful practice so I can sit down with a smaller group of students. What better way to provide feedback to students than to be able to sit with them and actually work with them and see them work and be able to provide feedback on the fly right there. Obviously written feedback is not a bad thing at all, but we do know that with time and then also sometimes I wonder how much written feedback actually gets utilized, especially as students get a little bit older and it’s passed.

Kyle: It’s not as timely when it’s written when I bring it home and I write it and then I bring it back. Sometimes I don’t get to it right away. That could be a challenge. Giving students the opportunity to reflect is great as well. I think in elementary, elementary teachers are so much better than I say, we on the secondary side are for doing things like journaling, giving kids the opportunity to reflect on the learning and just to give them that opportunity to essentially in a few sentences or a paragraph describe what they heard from the lesson today. I was in a meeting today and Yvette Lehman, she had mentioned that she would see kids head nodding in her class and she’s like, “All right, they all got this.” She would look at the reflections in their journal at night and it would be like completely off. It was like a mishmash of what she said versus what another student shared and it didn’t come together.

Kyle: That could be a great way just to understand what your kids know and then you can actually address it the next day when you got into class and actually provide them the feedback verbally. Finally, the last piece about feedback that I think is really important, feedback’s huge. This isn’t the only parts of feedback that’s important, but something I think we can often do which would defeat the purpose of this strategy of being the guide is by providing feedback that does too much telling and not enough asking questions. If a student’s doing this, what’s the question I can ask that student to get them to think along that path or to continue on their journey and not necessarily fix that mathematician? You referenced it earlier. Being the guide doesn’t mean you’re going to grab the sword from the hero and do the work for them. You want to actually try to help them learn through being more curious.

Kyle: We mentioned that book, The Coaching Habit, many times in the podcast before. The biggest piece I take away from that book is how do I be more curious instead of rushing to action and advice giving? There are times for that, absolutely, but how can I help and what’s the next question that will help them get to the next place? That is strategy number three. How about strategy number four, Jon? Take is into strategy number four here.

Jon: For sure. Okay, strategy number four is teach students, not stuff. What we mean here is that we’re teaching the students we have in front of us and not always focused on the exact curriculum content standards in getting that content standards out like what I mentioned earlier in the sense that my lessons would be like example, example, example, because I know that after completing those five examples I will have covered the curriculum because I have shown them exactly how to solve these problems because the curriculum standard said that students, by the end of this course, should be able to solve systems of equations, let’s say. We’re saying that that’s fine, we definitely need to use the curriculum as a guide, but we want to teach the students we have in front of us. There are so many things that are more important in our lessons than just always focusing on the curriculum standards.

Jon: I think this goes to the big idea that we’re talking about here in this podcast about we’re moving them to grade 10 and we’re just focusing on what are the curriculum standards that I have to get to them so that they could be prepared for grade 10? When you think about it, if you’re just giving out curriculum standards all the time … Okay, come on, how many times do you start your school year and you’re saying “Okay, let’s go right into Pythagorean theorem. You guys know the Pythagorean theorem?” Everyone’s like, “I don’t know what that is,” and you’re like, “Come on-

Kyle: I’ve never heard that before.

Jon: … it’s standard in grade eight said.” Or “The standard in grade nine said that you would know it. But don’t you know it?” How many times does this happen? It happens all the time. Kids aren’t always bringing it with you. When you think about if you’re just pumping out standards and curriculum guidelines, many of those students aren’t letting that sink in anyway. We have to think about who’s in front of us, teach our kids, not the curriculum standards all the time because there’s so many more important things out there. Kyle, what are some of the important things that we should be thinking about other than just the content standards?

Kyle: You nailed it with the content piece because essentially what that does and what it did in my classroom was it turned math class into this big, long semester of memorization, right? It was like, oh, you don’t remember that from last year? Okay, well, I’m going to re-teach that and then I’m going to reteach a little bit more. Now it’s just more stuff for kids to memorize except for that lucky handful that could either figure it out on their own or maybe they had some sort of parent at home that was helping them or maybe they were really into going online and finding videos to teach them about it. But really it just ends up being a bunch of stuff that kids learn for a very short period of time before it just fades into nothing. The other part that we really want to focus on and this is part of the curriculum, but it’s not often really considered.

Kyle: It’s this idea of, in Ontario, we call it a process expectations. In common core, you would know them as the standards for mathematical practice. In Ontario, we also have learning skills, which is in the curriculum, but yet we do a really poor job of actually helping students to actually get better at their learning skills. We actually, on our report cards, we give a G for good or E for excellent or S for satisfactory or N for needs improvement, but we don’t actually help kids develop those skills. You’ll actually see kids with the same letter for their entire high school career. Independent habits, G, G. What are doing to help them build that? I’m guilty of it. I still don’t know how I would hone in on that piece. To me, I’m thinking those are the parts that kids need. Those are the skills that they actually need to be successful in life.

Kyle: The process expectations, like in Ontario, we talk about one of them is problem solving. We have reasoning, improving, reflecting, right? That metacognitive piece. Selecting tools and computational strategies, connecting, representing, communicating. They really are very similar to some of our common core expectations. Jon, what are some of the common core mathematical practices for those who are outside of the US?

Jon: Yeah, similar, very similar. Makes sense of problems and persevere in solving them. Construct viable arguments and critiquing the reasoning of others. Reason abstractly and quantitatively. Model with mathematics. Attend to precision. Use appropriate tools and strategies. Look for and make use of structure. Look for and express regularity in repeated reasoning. Very similar to the Ontario process expectations, for sure.

Kyle: These are more of what if we’re talking about how do I help kids get ready from Kindergarten to grade one, to me those sound way more important than a lot of other things. Now, obviously, there’s other skills as well. This teacher wasn’t necessarily referencing just math class, but things like a student being able to recognize letters and there’s things that those kids are going … those skills that we want them to have. Definitely, let’s make it happen, right? Let’s make it happen. But can we do it in a play-based way? Of course we can, right? These are all things that we just want to be thinking about as we try to move from this idea of just getting the content out there and trying to actually help give students the actual skills and the actual understandings that they need as they move on.

Kyle: Let’s go ahead and dive into strategy number five which helps because it segues off of the idea of the mathematical practice expectations or standards from common core or the process expectations and for you and I, we love helping teachers to focus in on problem solving. We’re not saying only focus on problem solving, but when we teach through task it gives us the opportunity to access so many of these other areas, like this idea of reasoning improving happens through task and through solving problems that, hey, surprise, surprise, I haven’t actually seen my teacher solve five minutes prior to, right? We want kids to actually be problem solvers, not question repeaters or question re-doers or number swappers or any of those things. We want them to focus on building those problem-solving skills, which connect to all of those other pieces as well.

Jon: Yeah, if you think about it, if you’re not focusing on teaching through problems or teaching through task or teaching through activities you are actually not doing any of the processes. I shouldn’t say not any of the processes, but you’re not hitting those process expectations or the standards for mathematical practice on a regular basis. How often are you going to ask kids to reason and improve if you’ve just given them seven examples and then ask them to practice? You’re assuming that when they hit question eight, hey, they’re going to do some communicating because the question at the top says, “communicating question” or they’re going to do a problem solving question because it says, “problem solving” on the top. But how many of those questions are actually these things? This goes to the big idea here about what you want. Focusing on problem solving is huge for us because that can help us do those other things. That’s one of the things that I want my students to walk away from math class with.

Jon: At the beginning of these strategies we talked about what are your core beliefs as a math teacher of what you’re really doing in math class? For me, teaching problem solving is a core belief of what we’re doing. When I think about my students going to grade 10 or going to grade 11 or going off to university, I can confidently say that you know what maybe they’re not going to show you solving system of equations the exact same way that you think it might be done in your class or maybe the kids aren’t completing the square with all the exact procedural steps that you’re doing in your grade 11 class, but I can confidently say my students are really good problem solvers. They’re going to walk out of there better than they were before and I’m going to argue that they’re better than they would’ve been without me. I think that’s something that I want to hold true about that they might … You know what?

Jon: If I give them a whole bunch of x’s and y’s … This is a story that I get regularly is that in my grade nine applied class I taught the whole class all year through context. Every major idea that we talked about in that class was through context of some sort or the other. I would probably say that there was no x’s and y’s, just straight x’s and y’s in that course. My students were solving equations and representing linear relations and solving proportional problems just like the content standards say they would, but they didn’t see it in that x, y format. Sometimes we would throw that in there, but I was confident that they were solving problems and we were covering those curriculum standards while doing that.

Kyle: Yeah, you were building off of it, right?

Jon: Yeah.

Kyle: Build off the context and then let’s show how we represent this more abstractly.

Jon: Right, we’re definitely showing it abstractly in that particular class. How many times do we really need to see x over this or equals this over this for no reason. Do kids really want to solve those problems anyway? Do they really need to solve those problems anyway if there’s no context, especially in a grade nine applied program? But, yet, when they went to grade 10 in this particular year the teacher started with x’s and y’s and was like, “These kids don’t know anything.” I pulled this teacher aside and said, “You know what, if it’s taught in context, I betcha you will be surprised that these kids can solve some problems that you would expect them not to.” Because you started with x’s and y’s and you think the hard problems are the word problems, but they’re going to think those ones are the easy ones. We need to focus strategy. Number five, we’re calling focusing on problem solving because I think there’s so much more to be gained when we do that.

Kyle: Yeah, I think you summarized that idea about those learning skills I was telling you about where we often don’t really help students to get any better at them. I was independent studying or whatever the independent … now I’ve lost it. Independent studying I believe it is or independence might just be the one that I’m referencing. If a student’s just good, good, good, good, good, good and there’s no strategies to get better oftentimes we treat problem solving the same way. We just are like this student isn’t very good at problem solving. How do you get better at it? Well, we’ve got to do it. We have to spend more time doing it. We also don’t want to save it. We don’t want to save problem solving until kids have this big repertoire of procedures ready to go like the procedure is going to zap the problem for you. You have to actually think it through. You’ve got to actually understand the context. You’ve got to be able to put yourself in that context, mathematize it, and then that’s where you can start applying your conceptual knowledge and then build that procedural knowledge. Awesome stuff there with number five.

Kyle: Let’s move onto number six, which we’re going to say is called being realistic. This one here is just this idea that we need to know every student that comes into our classroom is coming at various places along their journey. As we mentioned earlier, the curriculum’s there to help us, but we need to hone in on what every student can do now and to determine what we can do to help push them too. Also, setting those mini goals. We don’t want to limit this. We don’t want to limit their mathematical thinking at all. We’re not saying like, “Oh, this student’s here so they’ll never be able to achieve that.” It’s just, let’s get to the next step now instead of worrying about this big, huge leap and then starting to overwhelm ourselves. We want to make sure that it’s not every student that’s going to be at the same place at the end of the course. We know that that’s not a realistic expectation for everyone to be at the exact same place. Let’s set realistic goals that are attainable, but then also continue to push through those goals. We’re not going to use those goals as limiting factors.

Kyle: Be realistic about where they are, but then also set yourself a realistic plan. I’m hoping by next week this student can do this. Guess what? If they can do it by two days from now awesome, what’s the new goal? These are mini goals that we can set for each and every student. We can do this through conversation and obviously feel free to document your pedagogical documentation can be so helpful. But at the end of the day, let’s make sure that the goal isn’t something that’s so large that now the student feels like it’s unattainable. You, even as the educator are feeling like, wow, we’ll never get there. It’s like thinking, “I want to lose 50 pounds” and thinking like “Wow, that’s a lot. How am I going to lose 50 pounds?” Well, no, let’s start with by next week I’m hoping to drop half a pound. Let’s do that. Guess what? If it’s a pound by next week, awesome. Set that new goal. What am I going to do to change and actually try to push that thinking forward?

Jon: These are definitely good ideas for being realistic and I think that’s something that we probably don’t do enough. Thinking about how realistic we can be. Going forward, when you start your course, I’m going to have all of these kids get to grade. They’ve all mastered the grade 10 or the grade 9 curriculum, so it ties back to what we talked about in our other strategies about what are the big ideas that you want to focus in on too. Getting realistic about setting those goals too. Okay, Kyle, what do you think? Let’s move into our final strategy, number seven.

Kyle: This one’s a quick one, a quick one to wrap it up.

Jon: Yeah, for sure. This one’s called share your thinking and pedagogical decisions with your department members, fellow teachers, administrators and parents. I think this can go a long way too. This myth that we’re talking about, getting our students ready for a particular grade level. We’re imagining that we have to do that because we’re scared about that teacher thinking that we’re a bad teacher because we’re not prepared when maybe we focused on different things like problem solving and understanding some of the concepts while we’re moving towards procedural fluency but not memorizing procedures is something that you and I know that we’re not focusing in on as much as understanding it and solving those problems. We encourage you to share your big beliefs and your strategies on your choices that you’ve made in your curriculum, in your course, with the teachers around you, the teachers in the next grade, the teachers in the grade before, your administrators so that they’re on board with you and the parents, the kids. How many parents are going to come in and go like, “This is not the math that I know,” like, “What are you doing?”

Jon: You want to share that information with them because the more information that these people around you have the better you’re going to feel about how successful you’re doing in the classroom and those kids are. I encourage you to do that for sure. Kyle, what do you think about this? You have any more tips to add about sharing your ideas?

Kyle: Yeah, the last one I wanted to mention and it just leaps off of what you’re saying here about sharing is also thinking about how do you collaborate with your fellow colleagues on why you’re doing these things. I know you’ve alluded to that, but I’m even wondering do we sit down as a department or as a divisional team or do we sit down as a school if it’s an elementary school and say what are the things we want kids to know, understand and do by the end of different grades or maybe divisions and really try to come to some sort of common agreements. This school-wide agreement can be so helpful so that you’re not going to have everybody and people aren’t going to just immediately shift beliefs. We can’t force it on anyone, but just to get that discussion started about what we value and understanding what our colleagues value is really helpful too because we need to know what were kids being expected to know, understand and do in a previous grade before they got to me.

Kyle: I know what the curriculum says in the grade level before me, but what did that teacher actually want from those students? How do we somehow, as a staff, try to come together and try to come to some of those common agreements. It might take a long time for it to feel like it’s common, but at least to get that conversation started, I think is really important. What we’re going to do here is just summarize all of these tips keeping in mind that you can download the tips sheet from makemathmoments.com/episode26 and we’ll announce it again at the end of the episode.

Kyle: Strategy one is know your student. Making sure you know who’s coming into your class, what do they know? Where are they at now? Where do I want to help bring them to and then what’s that very next step that we’re going to do? How about number two, Jon, number two?

Jon: This is know your curriculum. We were talking about knowing the landscape and the content and the big ideas of your course and curriculum content standards that you want to bring out to your students. Knowing that can help you free up some time, but also help you move your students along. Number three, Kyle.

Kyle: Awesome. Number three is be the guide. This is about us providing them feedback whether written, whether verbal, whether it’s in small group, whether it’s just taking that one on one time when you go by their desk. Be the guide. Let’s try not to fix their issues or fix their problems. Let’s try to figure out how do we get them to the next place through questioning, through purposeful questioning and help them move along their journey. Not do these huge leaps, but these little small leaps to get them to the very next place along that journey. How about number four, Jon?

Jon: Number four is teach students not stuff where we were talking about focusing in on the students and not always the exact curriculum content standards from your course. Because there is so many other things that we should be thinking about. We specifically the Ontario process expectations. Lots of good stuff in there that we should be focusing with our students and also the common core standards for mathematical practice. These are the things that sometimes get often overlooked when we teach a particular way, but are so much more meaningful to our students to move and be stronger in different grade levels. Kyle, number five, go for it.

Kyle: Yeah, number five is focusing on problem solving. What we mean is to have kids solving problems instead of Mr. Pearce up at the board solving problems and students copying. Even if I solve it with them where I give them a couple seconds or minutes to work on it. Kids are just going to sit and wait. Let’s get kids actually solving problems and let’s really push them through that productive struggle. Jon, number six.

Jon: Number six, which is about being realistic. We were recommending to you to set yourself some goals for your students, for you and planning because not always are we going to get every single student to master all of the content from that course to move to the next grade anyway. We want to remind you that you want to be realistic when we’re thinking about all of these strategies. Number seven, Kyle, the last one, bring it home for us.

Kyle: Yeah, the last one is to share and collaborate with your colleagues and your department members or your divisional teams because knowing what they value is really important. Let’s also share what we’re going to value and let’s see how do we build some common ground. The best way here, I think, is to do a little bit of giving and taking because remember all of it is important. Knowing, understanding and doing, all three are important. We want to make sure there’s a balance there. Maybe what we might be able to help people to see is maybe how we might approach things. Do we want to save problem solving until kids know all this stuff or do we want to actually help them build understanding through problem solving and by doing so that now they do know more stuff along the way?

Kyle: Those are seven strategies for you to consider as we try to overcome this unproductive belief about how we need to get kids ready for and then we just sort of blast through content. Let’s make sure that we’re trying to help every single student learn. It’s about their learning, not always about my teaching. Really, am I actually teaching if there is a student who is not learning? Let’s focus in on those things. Let’s start wrapping this up. Jon, where can people find us to let us know what they think about this episode and any of the other episodes.

Jon: We want you to reach out to us. We’re pretty passionate about this particular idea and all the other ideas from our podcast. We know you have thoughts on this. Tweet us @MakeMathMoments or email us at admin@makemathmoments.com or hit us up on the Facebook group Math Moment Makers K through 12. We’ll also be opening a topic thread inside our Make Math Moments Academy where we can dive into this in more detail. But we want to hear from you. I know that lots of people have different opinions about this idea. Bring them forward. Let’s keep this conversation going.

Kyle: Awesome. In order to ensure you don’t miss out on new episodes as they come out each week, be sure to subscribe on your favorite podcast platform. Also, if you’re liking what you’re hearing please share the podcast with a colleague and help us reach an even wider audience by leaving us a short review on iTunes, Spotify, Google Play or whatever platform you’re on. All of it helps and we appreciate it. We read every single one, so thank you for those so far.

Jon: Show notes and links to resources from this episode, plus the downloadable PDF on the seven strategies can be found at makemathmoments.com/episode26. Again, that is makemathmoments.com/episode26.

Kyle: Remember if you haven’t checked out the academy yet, you can do so right now, like right now by checking out makemathmoments.com/academy, that’s makemathmoments.com/academy. Well, until next time I’m Kyle Pearce.

Jon: And I’m Jon Orr.

Kyle: High fives for us.

Jon: And high fives for you.

Thanks For Listening

- Apply for a Math Mentoring Moment

- Leave a note in the comment section below.

- Share this show on Twitter, or Facebook.

To help out the show:

- Leave an honest review on iTunes. Your ratings and reviews really help and we read each one.

- Subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, and Spotify.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks